MAY 8, 2016

Our Hero

and His Blues:

Celebrating

Albert Murray

By Clifford Thompson

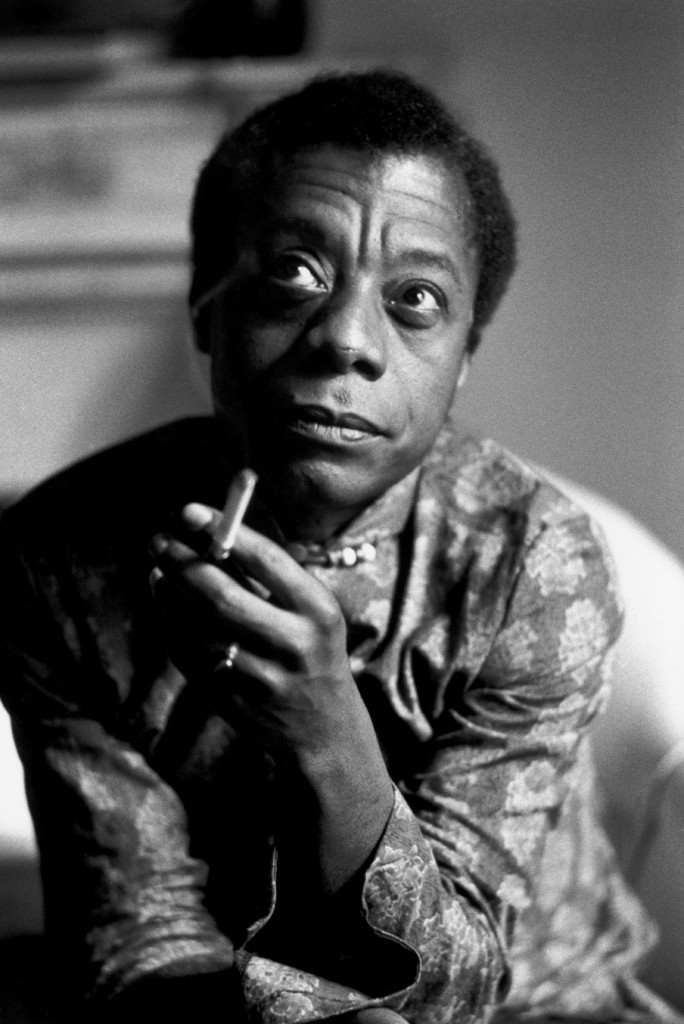

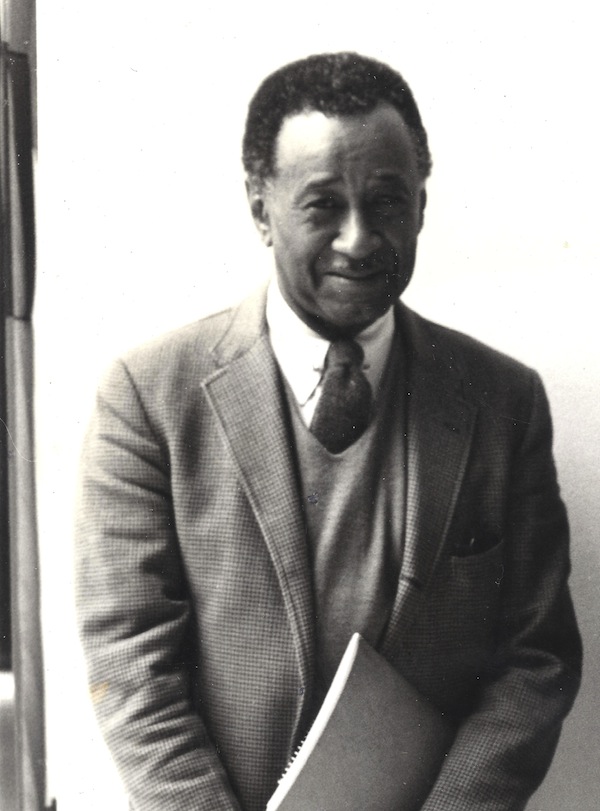

Albert Murray

THE WRITER ALBERT MURRAY would have celebrated his 100th birthday on May 12, and he nearly made it: he died in August 2013 at age 97. Murray was the author of more than a dozen books that celebrated the central place of blacks in American tradition, character, and culture. Himself a product of a southern black community, Murray saw the culture of that environment neither as defining his entire world nor as comprising a provincial set of mores and folkways whose confines he meant to transcend. Rather, he viewed black American culture as a worthy element of the culture of the nation and the world, and he viewed himself as something of a black American ambassador to that larger culture, to a menu of traditions and arts he meant to explore and savor, confident of the value of what he brought to the table, around the world and at home. For Murray, blacks in the United States have not only helped to define America, but have been largely if not mainly defined by it, and his works celebrate the history and results of that two-way process. Jazz and the blues, in the Murray view, stand both as concrete products of the black American tradition and as metaphors for black American history — representing the improvisation, resilience, and skill brought to bear on the task of surviving difficult times.

That last point is central to the Murray concept in two ways. First, Murray saw art, in all its forms, as originating in the central human task of creating order out of chaos, of making sense of the world, central because it is a key element of survival. Art, he wrote in From the Briarpatch File, is “fundamental equipment for existence on human terms.” And in The Omni-Americans: “Art is by definition a process of stylization, and what it stylizes is experience.” Simply put, according to Murray, art grows out of the need to make it in the world. Black slaves seeking freedom, an essential component of a fully human life, sang songs with coded messages for those plotting escape. Even on a day-to-day level, these songs, sung by slaves as they performed forced labor, inserted a human element into an inhuman situation, helping them to carry on; moreover, these songs, created by slaves and their descendants, brought black African traditions to an American context, and served as the origins of much of American music as a whole. Thus, what began as part of the process of survival was refined into an aesthetic statement.

Second, the challenges that art helps us to overcome are themselves fundamental to the human condition, providing what Murray often called “antagonistic cooperation” in the development of an artistic and heroic tradition. A hero needs a challenge to define himself or herself against; the brutal conditions faced by black Americans provided that challenge in this context, making the black American story not one of special pathos but a representative example of the larger human experience — representative, if extra exciting. As Murray wrote in The Omni-Americans,

The legendary exploits of white U.S. backwoodsmen, keelboatmen, and prairie schoonermen […] become relatively safe when one sets them beside the breathtaking escapes of the fugitive slave beating his way south to Florida, west to the Indians, and north to far away Canada through swamp and town alike seeking freedom — nobody was chasing Daniel Boone!

To paraphrase Murray in his book The Blue Devils of Nada: To fight dragons is heroic; to protest the existence of dragons is naïve. This view determined Murray’s approach to what he saw as the vitally important work of the storyteller, when it came to both analyzing the stories of others and creating stories of his own. Protest literature, he felt, simply made for second-rate storytelling. As he once said to me, “You don’t want the value of your novel to depend on who’s in the White House.” Worse, protest literature sold short the oppressed groups it was ostensibly meant to help, ignoring the variety and complexity of their experience — their humanity, in short — and reducing their status to that of victims. Murray found a standard for storytelling in the blues. Far from being a mere outpouring of sadness, or simple moaning, blues music represents an artful response to adversity and thus a way of keeping the blues at bay. In The Hero and the Blues, Murray writes about the protagonist of Thomas Mann’s four-volume novel Joseph and His Brothers. Joseph, he explains,

goes beyond his failures in the very blues singing process of acknowledging them and admitting to himself how bad conditions are. Thus his heroic optimism is based on aspiration informed by the facts of life. It is also geared to his knowledge of strategy and his skill with such tools and weapons as happen to be available. These are the qualities which enable him to turn his misfortunes into natural benefits.

Such tools as happened to be available to Murray included confidence in himself and in the value of his culture in the American family and the family of the world — the tools with which he faced that world and which allowed him to see himself as the equal of anyone in it.

He proved himself to be exactly that, over the course of his long, full life. Albert Lee Murray was born in Nokomis, Alabama, and grew up on the outskirts of Mobile in an area called Magazine Point. Soon after his birth he was adopted by Mattie Murray and Hugh Murray, who worked variously as a sharecropper, dockworker, and sawmill hand. When Mattie’s sister died, the Murrays adopted her children as well, giving Albert Murray three older siblings. The environment in which Murray grew up greatly informed his sensibility, steeping him in local southern black traditions while also exposing him to those who had traveled far and wide: blues singers performed at local juke joints, and the great black baseball player Satchel Paige, among other athletes and performers, sometimes passed through. As Murray told me when I interviewed him for Current Biography magazine in 1994, his love of storytelling was a natural result of his upbringing, since he spent a lot of time “sitting around the fireplace just listening to people talk.”

Like Scooter, the hero of Murray’s four novels, Murray didn’t know he was adopted until he got older. However, he seemed never to have felt unwanted; rather, he appeared, if the accomplishments of his boyhood and young manhood are any indication, to have been the object of a good deal of love and support. An athlete as well as an excellent student, he ran track, played football, and was captain of his school’s basketball team, and he was voted best all-around student at Mobile County Training School. At Alabama’s famed Tuskegee Institute, which he attended on a scholarship, he read the great contemporary literature of the day, including the works of Thomas Mann, Ernest Hemingway, and William Faulkner. He noted that when he took out books from the library, he looked to see who had checked them out before him, and one name turned up consistently — that of a student two years ahead, one Ralph Ellison, the future author of Invisible Man, who would later become of one of Murray’s close friends and his philosophical soul mate.

Following his graduation from Tuskegee, in 1939, Murray emerged as a true Renaissance man: after doing graduate work at the University of Michigan, he returned to Tuskegee to teach literature and direct student theatrical productions; he then enlisted in the US Army air force, in which, as an ROTC associate professor, he taught air science and tactics. Meanwhile, he indulged what he termed his “consuming passion” for jazz. Interwoven with periods of active duty in the air force were Murray’s graduate studies at New York University, where he received a master’s degree; while in New York he went to hear Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, and Miles Davis play on 52nd Street. Even his air force training came in handy here, since he was able to fly to New York from wherever he was stationed to purchase the latest jazz records and then fly straight back. As an airman he traveled widely, visiting Rome and Istanbul, for example, and soaking up world culture. In 1962, at age 46 (married with a daughter by then), Murray retired from the air force with the rank of major and settled in New York, teaching at a number of universities.

Ellison, also in New York, had already shot to fame: 10 years earlier he’d won the National Book Award with Invisible Man. He and Murray were friends by this time and had written many letters back and forth (later collected in the volume Trading Twelves); their correspondence reveals that Murray had begun to try his hand at fiction, though years would pass before he published any. He had, however, published essays in a number of journals. Some of those were collected in his first book, The Omni-Americans, published in 1970, when Murray was 54 years old.

¤

Unlike Ellison’s, Murray’s is not a household name. But it would be difficult to overestimate Murray’s influence on what are now multiple generations of writers and intellectuals, particularly those, as he himself might have put it, with brown skin. Speaking for myself, and for quite a few others whom I have conversed with and whose works I have read, the resonance of Murray’s writing has to do with its power to sort out a thinking person’s very understandable confusion over the issue of American identity. Given the history of blacks in this country, which began with slavery and has seen no shortage of discrimination and violation since slavery was officially abolished, it is easy for a black American to feel, at best, an emotional distance from the country where he has spent his entire life. This accounts — again — for the understandable appeal of the message from those American-born blacks who view themselves as Africans living on US soil; and I see no reason to take issue with blacks who embrace Afrocentrism, drop their Anglicized names for African names, and observe African or African-derived rituals. But for those who feel unable to embrace the traditions of a continent — Africa — that they may never have even visited, who, at the same time, feel emotionally distant from a home country where their lot has been discrimination, whose educations have taken them into integrated circles, there can arise a painful disorientation related to a central, root question: Who are we?

It is this question that Murray’s work has helped many of us to resolve. By pointing up the central place of blacks in American society, Murray’s writing has served as something of an invitation to a black American homecoming, illustrating for blacks the reasons for embracing America; reasons that go beyond the simple lack of an alternative. Simply put, blacks can call America home because they have helped shape this country through labor and through influence both cultural and genetic; in the process, blacks have created their own heroic tradition, one that has called for skill, improvisation, and grit, qualities symbolized, again, by jazz and the blues.

The word “heroic” is important here, because Murray’s emphasis on American identity should not be seen as representing a black capitulation to mainstream values. Murray’s radical notion, in fact, is that when it comes to American culture, blacks, at least in large part, are the mainstream. Murray called American society “incontestably mulatto,” and he once observed that Americans resemble no one so much as one another. And this, in turn, is why the value of Murray’s work extends beyond the black intellectual community to all Americans: it has much to tell all of us, black and white, about who we are.

This influence of Murray’s began with that first book of essays, The Omni-Americans. To put the appearance of that book in historical context: its publication, in 1970, came two years after the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., at a time when King’s message of love and nonviolent resistance to racist oppression had largely given way to the separatism and cultural nationalism of the black power movement. Thus, black Americans founds themselves divided into two camps — or trying to decide between them — with one still struggling to bring blacks and whites together and the other asserting black people’s independence from white influence and advocating black interests above all else, supported if necessary by violence. In this debate, Murray’s ideas represented a third way: neither a separating from the American mainstream nor an effort to bridge races, but an insistence that the bridge had long ago been built. While he harbored no illusions about many white Americans’ attitudes toward blacks, Murray nonetheless believed that being an American of any stripe involved the recognition of one’s interrelatedness, both cultural and genetic, to all those residing in the United States. And while one might easily assume that black cultural nationalism represented the more manly of the two options seemingly on the table for black Americans, Murray advanced the notion that it was, rather, a concession. In The Omni-Americans, he anticipates the work of Ta-Nehisi Coates by over four decades:

No one can deny that in [America] many somewhat white immigrants who were so unjustly despised elsewhere not only discover a social, political, and economic value in white skin that they were never able to enjoy before but also become color-poisoned bigots. Indeed, an amazing number of such immigrants seem only too happy to have the people of the United States regard themselves as a nation of two races. (Only two!) Many who readily and rightly oppose such antagonistic categories as Gentile and Jew, gleefully seize upon such designations as the White People and the Black People. But even as they struggle and finagle to become all-white (by playing up their color similarities and playing down their cultural differences), they inevitably acquire American characteristics — which is to say, Omni-American — that are part Negro and part Indian.

The bitterness of outraged black militants against such people is altogether appropriate even if sometimes excessive. The militants’ own insight into the pragmatic implications of the heritage of black people in America, however, is often only one-dimensional. Indeed, sometimes it seems as if they are more impressed by the white propaganda designed to deny their very existence than by the black actuality that not only motivates but also sustains them. In any case, when they speak of their own native land as being the White Man’s country, they concede too much to the self-inflating estimates of others. They capitulate too easily to a con game which their ancestors never fell for, and they surrender their birthright to the propagandists of white supremacy, as if it were of no value whatsoever, as if one could exercise the right of redress without first claiming one’s constitutional identity as citizen!

Murray’s insistence on the central and rightful place of blacks in American society did not prevent him from denouncing racism, both contemporary and historical, when the subject arose. But he reserved his most biting attacks not for outright racists — those, after all, supplied the “antagonistic cooperation” that in turn provided the context for heroic action; instead, those he opposed most vehemently were the proponents of what Murray liked to call “the folklore of white supremacy and the fakelore of black pathology.” That term referred to the work of social scientists and others, however well meaning, who made pronouncements about the black community that were based on little or no personal experience and that depicted blacks as a group made subnormal by centuries of oppression.

A particular target of Murray’s wrath was Daniel Patrick Moynihan’s highly influential 1965 Labor Department study, The Negro Family: The Case for National Action, which identified the absence of males from black homes and resulting black matriarchies as legacies of slavery and as characteristics that undermined black achievement. The report referred to the “emasculation” of the males in this matriarchal family structure and saw this perceived trait as being central to the dysfunctionality of the black family. Murray took issue with the report’s claims on grounds of logic, since this notion was plainly belied by the preponderance of illegitimate children fathered by men free of any domestic or otherwise “emasculating” constraints. He also attacked what he saw as the counterproductive effects of the Moynihan report, writing that “to most white people, sympathetic and antagonistic alike,” the report “has become the newest scientific explanation of white supremacy and thus the current justification of the status quo.” At a time, Murray writes in The Omni-Americans,

when Negroes were not only demanding freedom now as never before but were beginning to get it, Moynihan issued a quasi-scientific pamphlet that declares on the flimsiest evidence that they are not yet ready for freedom! At a time when Negroes are demanding freedom as a constitutional right, the Moynihan Report is saying, in effect, that those who have been exploiting Negroes for years should now, upon being shown his statistics, become benevolent enough to set up a nation-wide welfare program for them […] Moynihan’s arbitrary interpretations make a far stronger case for the Negro equivalent of Indian reservations than for Desegregation Now.

The Moynihan Report, Murray notes, “charts Negro unemployment, but not once does it suggest national action to crack down on discrimination against Negroes by labor unions. Instead, it insists that massive federal action must be initiated to correct the matriarchal structure of the Negro family!”

What is important to note here is that Murray was not denying that there were challenges to overcome within the black community. “Instead of the alleged cycle of illegitimacy-matriarchy and male emasculation by females, which adds up to further illegitimacy,” Murray writes, “the problem of Negro family instability might more accurately be defined as a cycle of illegitimacy, matriarchy, and female victimization by gallivanting males who refuse to or cannot assume the conventional domestic responsibilities of husbands and fathers.” Here Murray makes a crucial distinction, because while Moynihan’s theory was a statement about how black people are, Murray’s was based on what they do; while one implies helplessness and a need for intervention by others, the other credits blacks with agency.

Underlying Murray’s response to the Moynihan Report was his belief in the values that had allowed the black community to survive — whether those values are rooted in matriarchy or not — and his refusal to accept an image of himself imposed from without, no matter how good the intentions of those who sought to impose it. That theme recurred throughout Murray’s work. Also implicit in his criticism of the Moynihan Report is his preference for heroic action — exemplified here by those blacks insisting on their rights as equal Americans — over the acceptance of ideas based on condescension if not out-and-out racism.

¤

Murray’s writing can be divided roughly into four areas of exploration that often overlap and that all share the same philosophical underpinnings. One area comprises his observations on race, of which The Omni-Americans is the prime example; another focuses on literature; still another, music; and last is his work evoking the black southern culture that produced him. In this last category, the first work to be published was the quasi-memoir South to a Very Old Place (1971), and the other four works are novels. If The Omni-Americanshad announced Murray’s worldview, South to a Very Old Place found his voice fully developed. Murray’s writing has been called “jazz-like,” and while that adjective has been applied far too loosely, in Murray’s case it is actually appropriate. The writing in The Omni-Americans is marked by a forward thrust that is akin to melody, but in South to a Very Old Place, we find the writer, one might say, exploring the chords that undergird that melody — operating, in other words, like a jazz soloist.

Musical lines in jazz are longer than those in pop music and contain more notes, and those notes explore a greater number of ideas. Murray’s sentences often operate in a comparable way. Take this single, long example from South to a Very Old Place:

But what strikes you most forcefully as you find your way around Morehouse this time is how specifically [Martin Luther] King also embodied the very highest ideals of the splendid black, brown, and beige Morehouse Man who whether Alpha, Kappa, Sigma, or Omega was forever dedicated to the proposition that for those precious few Negroes who were privileged to come by it — by whatever means — a college education was a vehicle not simply for one’s own personal gain but for the uplift both social and spiritual of all of one’s people.

A simple enough message there, seemingly: for Martin Luther King and other black Morehouse students, getting a college education meant not just getting ahead yourself but helping other blacks to do so, too. But in Murray’s hands, it is not so simple after all. He might just have written here “the splendid Morehouse Man” or “the splendid black Morehouse Man,” but with “the splendid black, brown and beige Morehouse Man” he adds resonance that reflects the varied experience of the black community; note, too, that he writes not “black, brown, or beige” but “black, brown, and beige,” which is simultaneously a reference to a work of that title by the black jazz hero Duke Ellington and a suggestion that a Morehouse Man carries with him the concerns of all of his people. And there’s more: “whether Alpha, Kappa, Sigma, or Omega,” Murray writes, naming of the different fraternities on campus, commenting again on the varied nature of experience within that single milieu. “For those precious few Negroes who were privileged to come by it — by whatever means — a college education was a vehicle …”: the three-word phrase “by whatever means,” set off by dashes, contains a glimpse of the great variety of people and circumstances involved. Finally, there is “the uplift both social and spiritual of all of one’s people.” The term “racial uplift” is common, but here Murray explores, with “social and spiritual,” the wider implications. Murray uses words the way a jazzman uses notes.

Music informed not only the crafting but also, to an extent, the subject of South to a Very Old Place: at one point, Murray urges black leaders of the day to bring to the struggle for equal rights the resourcefulness and improvisatory skill that jazzmen bring to music. At another, describing a conversation among some of his Alabama “homefolks,” Murray compares their voices to instruments in a band. This portion of the book embodies Murray’s concern with both storytelling and music: the subjects, respectively (but not without overlap), of his next two books.

The short 1973 volume The Hero and the Blues began as a series of lectures Murray gave at the University of Missouri. In proposing a theory of literature based on the tenets of art rather than protest, Murray was not downplaying the relevance of the writer to his or her own time; instead, he saw the function of the writer, or literary storyteller, as being not unrelated to but above that of the protest novelist or political pamphleteer. “It is literature, in the primordial sense, which establishes the context for social and political action in the first place …,” Murray writes in The Hero and the Blues. He continues,

It is the writer as artist, not the social or political engineer or even the philosopher, who first comes to realize when the time is out of joint. It is he who determines the extent and gravity of the current human predicament, who in effect discovers and describes the hidden elements of destruction, sounds the alarm, and even (in the process of defining “the villain”) designates the targets. It is the storyteller working on his own terms as mythmaker (and by implication, as value maker), who defines the conflict, identifies the hero (which is to say the good man — perhaps better, the adequate man), and decides the outcome; and in doing so he not only evokes the image of possibility, but also prefigures the contingencies of a happily balanced humanity and of the Great Good Place.

How is what Murray describes here different from protest literature? Two words are key: “hero” and “possibility.” In naturalism, or protest literature, the courses of characters’ lives are determined by the societal conditions in which they live, and improving those lives necessitates dismantling whole systems; therefore there are no heroes, since heroic struggle implies the possibility of individual victory, and in protest literature that possibility does not exist. And since the “good” characters in these novels are powerless to change their lives, protest literature amounts to an appeal to powerful “bad” people, or, as Murray terms them, “dragons.” “In effect,” Murray writes,

protest or finger-pointing fiction such as Uncle Tom’s Cabin and Native Sonaddresses itself to the humanity of the dragon in the very process of depicting him as a fire-snorting monster: “Shame on you, Sir Dragon,” it says in effect, “be a nice man and a good citizen.”

But in Murray’s view, the work of the storyteller as artist entails describing life in all of its squalor, and beauty, and possibility, and heroism, and it entails confronting the realities of life, the way a blues musician does.

And so, even Murray’s books about literature are about music! But Murray took music itself as his subject in Stomping the Blues, published in 1976. Early on in that volume, he draws a crucial distinction between the blues — or feelings of sadness — and blues music, which, “with all its preoccupation with the most disturbing aspects of life,” as Murray writes, “is something contrived specifically to be performed as entertainment.” Murray goes on in the book to discuss heavyweight practitioners: not only blues but also jazz musicians, offering insightful commentary on the likes of Bessie Smith, Billie Holiday, Coleman Hawkins, Lester Young, and many others.

Also in the area of music, Murray collaborated with Count Basie on the great bandleader’s autobiography, published in the mid-1980s, a book that took a decade to write and that sadly appeared after Basie’s death.

Murray’s work with music was not limited to writing. Later in the 1980s he co-founded the Jazz at Lincoln Center program with the celebrated trumpeter Wynton Marsalis. Marsalis had been greatly influenced by the writer Stanley Crouch, on whom Murray was the chief influence; with Crouch’s rise to prominence, signaled by the publication of his essay collection Notes of a Hanging Judge, in 1990, more attention was focused on Murray. Indeed, it was an essay about Murray in Hanging Judge, titled “Chitlins at the Waldorf” (originally published in the Village Voice), that brought Murray to my own attention. Murray’s work, Crouch wrote, “is that of a writer who knows that to be all-American is to be Indian, African, European, and Asian, if only through cuisine.” The 1990s brought Murray more attention still, with the success of Jazz at Lincoln Center and Henry Louis Gates Jr.’s 1996 New Yorkerprofile, titled “The King of Cats,” which ended with the line, “This is Albert Murray’s century; we just live in it.” Murray appeared on television frequently beginning in the 1990s, and he published more books, including the essay collection The Blue Devils of Nada, which includes pieces on jazz, visual art, and literature, and the second and third novels in what would be the Scooter tetralogy.

¤

It is the great irony of Albert Murray’s career that in his own work as a fiction writer the heroic struggle he celebrates in other works is mostly absent. This is not to suggest that Murray wrote protest novels — he most assuredly did not — or that his main character and alter ego, Scooter, is not the chief determiner of his own fate, because he most certainly is. Rather, the “antagonistic cooperation” to which Murray often refers, or the difficult conditions against which the protagonist must struggle to be a hero, do not exist in his own four novels. In the first, Train Whistle Guitar, we are introduced to Scooter during his childhood in the South; in The Spyglass Tree, Scooter attends a southern college and gets caught up in a local confrontation that is resolved not only very easily but also, as it were, off-screen; The Seven League Boots finds Scooter traveling as a bass player with a famous jazz band; and in The Magic Keys, Scooter, like his creator, has moved to New York. In these novels, Scooter has all the fun of a storybook hero — traveling here and there and getting the girl — without any of the obstacles. It’s difficult to recall a moment of self-doubt in Scooter, and not only does he face no opposition from others, but those others appear to compete with each to see who can offer Scooter the greatest number of compliments. As one reviewer of The Magic Keys put it, “whatever Scooter touches turns to praise,” and in the essay that severed his friendship with Murray, Stanley Crouch referred to “the legions of the Scooter-awed.”

At a symposium on Murray held at Columbia University in February 2016, the Murray scholar Paul Devlin, who edited the forthcoming Murray Talks Music: Albert Murray on Jazz and Blues, proposed an interesting theory about the ease with which Scooter moves through the world. If, as John S. Wright has suggested, the problems facing Ellison’s Invisible Man are those of the innocent hero of a bildungsroman who finds himself in a picaresque novel, then Scooter is the picaresque hero, by nature a trickster figure, with the great good fortune to inhabit a bildungsroman.

In all the novels, however, even when they are marred by the lack of obstacles in Scooter’s path, there is a wonderfully evoked sense of setting; this is particularly true of the first, Train Whistle Guitar, perhaps because it reflects the most fondly remembered scenes of the writer’s own childhood. In the following passage from early in that novel, in which the boy Scooter talks about his best friend, Little Buddy Marshall, and about a local hero known as Luzana Cholly, Murray conveys the sights and smells of this black southern world:

The color you almost always remember when you remember Little Buddy Marshall is sky-blue. Because that shimmering summer sunshine blueness in which neighborhood hens used to cackle while distant yard dogs used to bark and mosquito hawks used to flit and float along nearby barbwire fences, was a boy’s color. Because such blueness also meant that it was whistling time and rambling time. And also baseball time. Because that silver bright midafternoon sky above outfields was the main thing Little Buddy Marshall and I were almost always most likely to be wishing for back in those days when we used to make up our own dirty verses for that old song about it ain’t gonna rain no more no more.

But the shade of blue and blueness you always remember whenever and for whatever reason you remember Luzana Cholly is steel blue, which is also the clean, oil-smelling color of gunmetal and the gray-purple patina of freight train engines and railroad slag. Because in those days, that was a man’s color (even as tobacco plus black coffee was a man’s smell), and Luzana Cholly also carried a blue steel .32-20 on a .44 frame in his underarm holster. His face and hands were leather brown like dark rawhide. But blue steel is the color you always remember when you remember how his guitar used to sound.

No discussion of Train Whistle Guitar would be complete without a mention of the way Murray captures southern black speech. In September 2013, I was present at Murray’s memorial service, at which Wynton Marsalis himself read the following sections of dialogue from the novel. (I concluded that if Marsalis had not settled for being the face of contemporary jazz, he might have made a fine actor.) In this section, Scooter is on his front porch in the middle of the night, in the company of adults, his head on the lap of his mother, Miss Melba; the adults assume incorrectly that Scooter is sleeping and begin to discuss the subject of his biological parents:

Miss Minnie Ridley Stovall sucked her gold teeth twice as she always did when she was gossiping about something and I knew she was going to say something more, and she did.

Of course me, myself, it ain’t none of my business, Jesus. Lord knows I know that, Miss Melba. So that’s why like I say I ain’t never asked you a thing about any of it before, and I don’t even know who the one started it. All I know is what everybody keep saying. So I just say to myself, I’m going to ask Miss Melba. That’s the only way to set em straight, if you don’t mind, Miss Melba.

Folks always running their mouth about something, Mister Horace Upshaw said. If it ain’t one thing it’s another, and if it ain’t another it’s something else.

It sure God is, Jesus, Miss Minne Ridley Stovall said.

And don’t none of them know the first thing about it, Miss Liza Jefferson said, Not a one.

That’s exactly why I said I was going to ask Miss Melba, Miss Minnie Ridley Stovall said. If you don’t mind, Miss Melba.

Ask me what? Mama said.

About Edie Bell Boykin, Miss Minnie Ridley Stoval said.

Ask me what about Edie Bell Boykin? Mama said, and the way she said it made me suddenly numb all over.

Some of them saying he really belongs to her, Miss Minnie Ridley Stovall said.

He belong to me, Mama said.

See there, Mister Horace Upshaw said.

But before anybody else could say anything else Mama’s stomach was vibrating again and I felt the sound start and heard it go and then it came out through her mouth as words:

She brought him into the world but he just as much mine as my own flesh and blood. I promised her and I promised God.

¤

There is no doubt, as noted, that Murray’s work has influenced generations of black writers and thinkers, as well as artists and scholars of many other stripes. But I would argue that his work and ideas have relevance far beyond intellectual circles, and, indeed, are sorely needed in the everyday, divided world we all face in America today.

The killing of Trayvon Martin, the killing of Michael Brown, the killing of Eric Garner, the killings of too many other young black males to name, the disproportionate incarceration rates of people of color, the disproportionate level of poverty among people of color, the need for black parents to tell their sons to be careful when so much as stepping out of their homes — all of this suggests many injustices, of which I will mention two: the first is the obvious bias of the police, the very people who are supposed to protect innocent people; and the second is the sense of hopelessness these events can certainly engender among black children, particularly those who are poor, as a significant number are. In the midst of all this, teaching Murray’s ideas, not only in college and university settings but as basic components of a primary school education, would fill a desperate need in at least two corresponding ways. First, for anyone who is raised or conditioned to see black Americans as “other,” Murray’s ideas would introduce the notion of the interconnectedness of all Americans, in terms of culture and genetics; a police officer less inclined to view a black man as an alien being might just be a little slower on the draw than one accustomed to equating all blackness with criminality. Second, related and just as important, Murray’s concept of the heroic black American tradition would serve as emotional sustenance for black children who live with the constant message that they are not valued and worthy — that they do not belong. Black kids need to learn what people who look like them have accomplished in America in spite of the odds: they need to hear not only isolated stories but a narrative of heroism in the face of times worse than our own — of heroism on the part of blacks who understood themselves to be American, and who fought for their rightful place in these United States.

I cannot think of work more important than Murray’s for helping to instill these ideas — for giving our children a sense of their own rightful place, as well as their history. Let us make sense of the world, and order from the chaos. Let us survive.

¤

+++++++++++

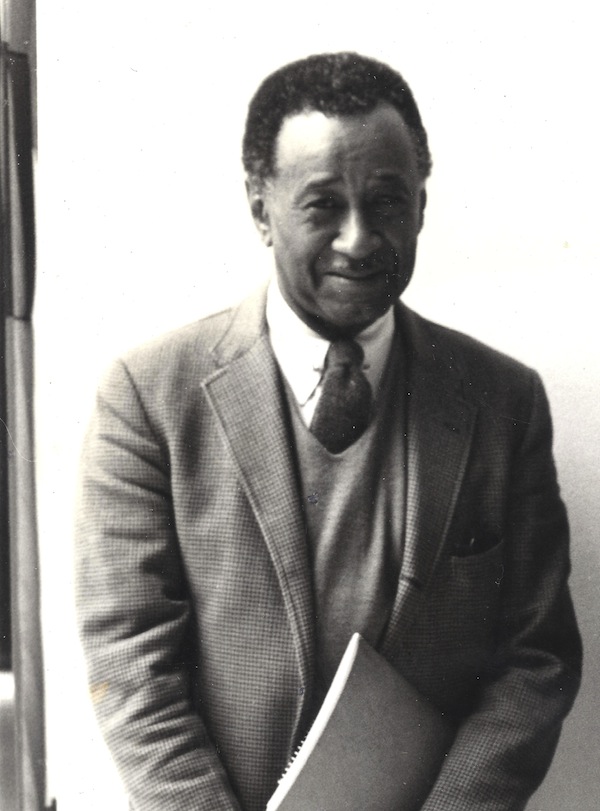

Clifford Thompson is the author of Twin of Blackness: A Memoir, Love for Sale and Other Essays, and a novel, Signifying Nothing.

>via: https://lareviewofbooks.org/article/hero-blues-celebrating-albert-murray/