The Scout Oath: “On my honor, I will do my best to do my duty to God and my country and to obey the Scout Law; To help other people at all times; To keep myself physically strong, mentally awake, and morally straight.”

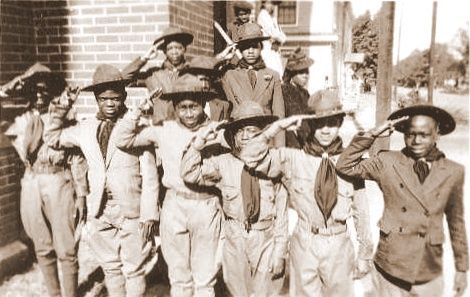

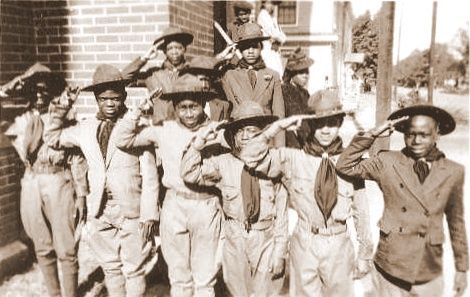

This date celebrates the founding of America’s first “Negro Boy Scout” troop in 1911. Initially started in Elizabeth City, North Carolina, opposition was encountered immediately, but troops continued to meet in increasing numbers. In 1916, the first official Boy Scout Council-promoted Negro Troop 75 began in Louisville, KY. By the next year, there were four official black troops in the area. By 1926, there were 248 all-black troops, with 4,923 black scouts and within ten years, there was only one Council in the entire South that refused to accept any black troops.

The founding of America’s first “Negro Boy Scout” troop, July 31, 1911

During this time as more troops started up, the Inter-racial Committee was established in January of 1927, with Stanley Harris as its leader. Also as part of the Boy Scouts of America (BSA) Inter-racial Service was “Program Outreach,” a program that combined racial minorities with rural, poor, and handicapped boys. These programs were often ineffective, especially with immigrants who feared the BSA as a means to recruit for the Army. Another problem with Program Outreach was that it often didn’t distinguish between the boys it viewed as “less chance” and those who were simply not white.

For example, the program’s reports categorize some scouts as “Feeble-minded, Delinquency Areas, Orphanages, and Settlements.” Many of the scouts in “Delinquent Areas” were blacks, who were measured as “Special Troops.” Instead of embracing black Scouting, the BSA systematically categorized blacks, bringing a literal meaning to “racial handicap” as the color of their skin was why they were considered “special.”

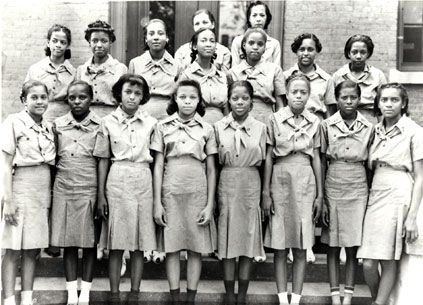

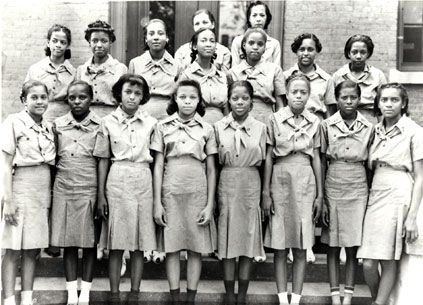

First African American Girl Scout Troop, ca. late 1930s

Scouting for minorities wasn’t just confined to cities, Scouting in rural areas were also common. One of these programs was called “railroad scouting,” where employees of the BSA would ride trains throughout the rural South, stopping at every town on the way to distribute information and encourage the formation of troops. This policy originated to cut down on railroad vandalism, and the BSA realized it was a great way to promote its organization. Native Americans were also a large portion of the minority Scouts, and lived in settlements in rural areas. With the help of these programs, the two Southern Regions, Region V in Memphis and Region VI in Atlanta, had growth rates of 28.2% and 47.9%, respectively. In 1937, 57.9% of black Scouts were from these two regions.

By the 1960s, with the industrialization of the South, the BSA shifted more towards urban expansion and improvement. In 1961, the Inter-Racial Service turned into the Urban Relationship Service and added inner-city children of all races. William Murray, author of “History of the Boy Scouts,” wrote, “Negro lads in the South and in the northern industrial centers were somewhat out of the stream of American boy life and needed special aid.” The Inner-City Rural Program was also developed to expose rural Scouts to the city and vice versa, but was small in scope. Programs targeting gangs were unexpectedly successful, and in many cities as many as 25% of boys living in housing projects were enrolled in the Scouts, many former gang members.

In the South, with the “separate but equal” mindset of the times, black troops were not treated equally. They were often not allowed to wear scout uniforms, and had far smaller budgets and insufficient facilities to work with. The BSA on a national level was often defensive about its stance on segregation. “The Boy Scouts of America] never drew the color line, but the movement stayed in step with the prevailing mores.” Even so, there was only one integrated troop before 1954 in the Deep South compared to the frequent occurrence of integration in the North. Also, the Scouts in the South did not support social agencies that were allies of the BSA. The YMCA was historically one of the BSA’s strongest supporters, but in Richmond, Virginia, blacks were not allowed to use the Y’s facilities to earn merit badges, specifically for swimming.

While nationally the BSA has a large endowment (approximately $2.6 billion), local councils had to raise money on their own. BSA is not a non-profit organization, and if local councils had pushed for integrated troops, it would not have gone over well with the general public and it would have made raising money difficult. It would have also been dangerous, because the Ku Klux Klan had strongly denounced the Scouts for even having segregated black troops. They claimed the BSA was a puppet of the Catholic Church, and it was not unheard of for Scout Jamborees and rallies to be broken up, often violently, by the Klan.

After the Civil Rights Act, slowly, troops began to integrate throughout the nation, even in the South. Currently several troops remain all black. After integration, many segregated black organizations, especially churches, remained segregated, not by law but by choice. It provided a heightened sense of community and unity that complemented their internal needs. If they made it this far under such extreme oppression, why should they happily submit themselves to white churches and social clubs? Since these organizations sponsored such a large number of Scout troops, many remained all black by choice. In 1974, after 53 years of segregation, the Old Hickory Council (North Carolina) and BSA councils throughout the South, started to integrate troops.

As an organization dedicated to developing morally strong and virtuous men out of boys, the BSA stresses the importance of understanding what it means to be a Scout. When applying for the Eagle Scout Award, the highest rank in Scouting, applicants must submit an essay along with documentation of their earned merit badges. In the essays, Scouts are asked, “In your own words, describe what it would mean to you to become an Eagle Scout.” Essay lengths differ greatly, from one sentence to four handwritten pages. Generally, Eagle Award applicants write about what it has meant to work several years to receive this award, and what they plan on doing after the receive it.

In the responses immediately following integration, different values and goals emerged based on race and oppression. One young man says, “When applying for a job or trying to enter college being an Eagle Scout is a great advantage.” “Being white in Winston-Salem, opportunities to go to college and to get a good job were there. As a black young person, such opportunities did not always exist, and instead of mentioning college and a job, there was a tendency to make more references to the army and military. Not necessarily saying outright that a future in the military is what they are striving for, but there are references like, ‘[if I get my Eagle Award] it will be like ‘becoming an Eagle Scout is like being a Captain or lieutenant in an army, working towards the Generals position.'”

Historically, the military has been one of the few ways blacks achieved distinction and respect. These youths had seen their fathers and uncles come back from World War II and the Korean War with medals and get the help of the G.I. Bill. Many saw this as their only way to eventually get into college or have a good career. With the aid of the civil rights movement, black Scouts saw the Eagle Award as a further means of proving their dignity and achievement. blacks in the first half of the 20th century were not allowed much dignity. America and the South were set up to make sure this dignity was never achieved. Through Scouting, black young people finally had something to be proud of, something that would make them, in at least one realm, equal or even superior to white children. It gave them a sense of identity that was lacking for centuries. They were no longer just “Boy,” they were an Eagle Scout.

Before de-segregation, in nearly all-white Eagle Scout applications, the essays included references to leadership opportunities to come out of their Award. Leadership is mentioned much less often among the black applicants, having not seen the same opportunities for leadership in their communities as they progressed through the Scouts. Another theme among the pre-civil rights applications was the frequent mentioning of God and Church in the white applications, compared to the black applications. The white applications tended to connect God and Country together as an important trait of an Eagle Scout, as, for example, “The Eagle award would show me that I have been doing my duty to God and my Country as a Scout.” The black Scouts did not mention citizenship nearly as often and when they did, it was usually in a secular manner. “I am an American on whom the future of this wonderful Country depends . . . learning to be of service to others.” This distinction the result of the lack of citizenship experienced by blacks from the beginning of this country.

It is telling that an organization like the Boy Scouts of America, dedicated from its inception to raising men of high moral strength and conviction supported racism. But at the same time, on a national and local level, the Scouts did have certain leaders that pressed against the grain of society for racial change. In the end, though, our most valuable insight is into the minds of these young black men who wrote of an equal chance for distinction and success in their Eagle Award essays. This relatively small achievement may have helped and inspired them to push on in their fight for liberty.

Contributing reference:

Kurt Banas,

Wake Forest University

Winston-Salem, North Carolina

336.758.5255