August Wilson,

The Art of

Theater No. 14

Interviewed by Bonnie Lyons, George Plimpton

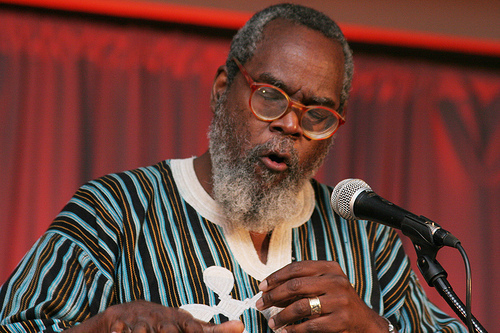

August Wilson has been referred to (by Henry Louis Gates, Jr.) as “the most celebrated American playwright now writing, and . . . certainly the most accomplished black playwright in this nation’s history.” Earlier this fall the beneficiary of Mr. Gates’s praise was in Atlanta to oversee the production of one of his plays. He took time off to meet for lunch at the Sheraton Hotel’s Fourteenth Street Bar, arriving in a black turtleneck sweater under a tweed coat. The tables in the bar are set up on a balcony overlooking the yellowgold emporium that is the hotel lobby. Wilson, who gave up cigar smoking years ago—though he lit one up upon the birth of his daughter, who is now two years old—asked to sit in the smoking section. No cigar on hand, he had purchased a pack of cigarettes at the lobby newsstand downstairs. He said he would give up cigarettes soon, as it would be ridiculous not to be around when his daughter goes to college.

A word about the playwright. Born on April 27, 1945, Wilson grew up in a workingclass area of Pittsburgh. His father, a GermanAmerican baker, abandoned the family when his son was only five. Wilson’s mother remarried and the family moved to a mostly white suburb. Fed up with racial indignities, he dropped out of school at sixteen and his real education started, so he has stated, in the local library. In 1968 he was a cofounder of Black Horizons Theater Company, though his artistic voice at the time was expressed in poetry. In 1978 he moved to St. Paul, Minnesota, where he wrote his first major play, Jitney. A subsequent play, Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom, submitted to the Eugene O’Neill Theater Center, came to the attention of Lloyd Richards, then artistic director of the Yale Repertory Theater. Richards helped Wilson refine the play, which then opened in 1984 in New Haven. Hailed as the work of an important new playwright, the play came to Broadway later that year, and marked the start of an astonishing career—including two Pulitzers (Fences and The Piano Lesson) and a number of Drama Desk Awards, as well as a Tony Award for works that include Joe Turner’s Come and Gone, Two Trains Running, Seven Guitars, and King Hedley II.

Though softspoken, Wilson is a man of strong convictions about the role of blacks in this country and from the first has involved himself in “trying to raise consciousness through theater.” He has an astonishing memory—the envy of those aware of it—and equal abilities as a mimic. With consummate skill he can shift his voice, which bears hardly a trace of a regional accent, into the rich patois of the South when he mimics the railroad porters he met as a boy in Pat’s Place in Pittsburgh.

In 1997 a widely publicized debate took place in New York’s Town Hall between Wilson and Robert Brustein, the artistic director of the American Repertory Theater in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Wilson’s position, based on W. E. B. DuBois’s principles (described in 1926 in his magazine The Crisis), was that the plays of a true black theater must be, in brief, “1) about us, 2) by us, 3) for us, and 4) near us.” Brustein criticized Wilson’s views as “self-segregation” and argued that funds for “black theater” on those terms would be foundationfunded “separatism.” Wilson repeated a statistic throughout the evening—that of the sixtyfive theaters belonging to the League of Regional Theaters, only one was black, the Crossroads Theater in New Brunswick, N.J. “The score is sixtyfour to one.” He pleaded for a black theater that would not have to rely on white institutions or make its appeal to white audiences. The debate was spirited, if inconclusive. And reasonably polite. At its conclusion Brustein referred to Wilson as a “teddy bear.” Wilson fended off the compliment: “I may be personable, but I assure you I am a lion.”

INTERVIEWER

What do you suppose Robert Brustein meant when he referred to you at the close of your Town Hall debate as a “teddy bear”?

AUGUST WILSON

I think he was expecting someone with a more strident tone and antagonistic demeanor. I think he was surprised to find out that I’m a pretty likable person, and that despite out different views I conducted myself with a civility and grace of manners my mother always demanded of me. For myself, I found him to be a more likable person than I had imagined. And I certainly value and respect the contributions that he has made to the theater; our differences of opinion on black theater do not dampen my respect and appreciation, nor in any way invalidate the considerable contributions that he has made.

INTERVIEWER

Can you say what first drew you to the theater?

WILSON

I think it was the ability of the theater to communicate ideas and extol virtues that drew me to it. And also I was, and remain, fascinated by the idea of an audience as a community of people who gather willingly to bear witness. A novelist writes a novel and people read it. But reading is a solitary act. While it may elicit a varied and personal response, the communal nature of the audience is like having five hundred people read your novel and respond to it at the same time. I find that thrilling.

INTERVIEWER

When did you first become involved?

WILSON

In 1968, during the Black Power movement, when black Americans were, as one sociologist put it, “seeking ways to alter their relationship to the society and the shared expectations of themselves as a community of people.” As a twenty-threeyearold poet concerned about the world and struggling to find a place in it, I felt it a duty and an honor to participate in that search. With my good friend Rob Penny, I founded the Black Horizons Theater in Pittsburgh with the idea of using the theater to politicize the community or, as we said in those days, to raise the consciousness of the people.

INTERVIEWER

Does that mean you were looking for plays that dealt with those issues? What kind of plays did you produce?

WILSON

We did everything we could get our hands on. Scripts were rather scarce in 1968. We did a lot of Amiri Baraka’s plays, the agitprop stuff he was writing. It was at a time when black student organizations were active on the campuses so we were invited to the colleges around Pittsburgh and Ohio, and even as far away as Jackson, Mississippi.

INTERVIEWER

You were the director.

WILSON

And I acted when the actors didn’t show up. As the director, I knew all the lines and I took over more times than I wanted to. I didn’t know much about directing, but I was the only one willing to do it. Someone had looked around and said, “Who’s going to be the director?” I said, “I will.” I said that because I knew my way around the library. So I went to look for a book on how to direct a play. I found one called The Fundamentals of Play Directing and checked it out. I didn’t understand anything in it. It was all about form and mass and balance. I flipped through the book and there in Appendix A I discovered what to do on the first day of rehearsal. It said, “Read the play.” So I went to the first rehearsal very confidently and I said, “Okay, this is what we’re going to do. We’re going to read the play.” We did that. Now what? I hadn’t got to Appendix B. So I said, “Let’s read the play again.” That night I went back to the book and sort of figured out what to do from that point on.

INTERVIEWER

Did you have a theater?

WILSON

No. We worked in the elementary schools—they let us use the auditoriums there. That was our base of operations. The audiences were mostly black. We charged fifty cents admission. Eventually that got up to a dollar. We literally went into the street a halfhour before the show and talked people into going in. Once they got in, they really liked it: “Hey, hey, you gonna do another play?” “Next Thursday.” “I’m gonna be there!”

INTERVIEWER

Were you writing plays at the time?

WILSON

I was writing poetry. But I found the theater such an exciting experience that one day I went home to try. I had one character say to the other guy, “Hey, man, what’s happening.” And the other guy said, “Nothing.” I sat there for twenty minutes and neither of my guys would talk. So 1 said to myself, “Well, that’s all right. After all, I’m a poet. I don’t have to be a playwright. To hell with writing plays. Let other people write plays.” I didn’t try to write a play for a number of years after that first experience.

INTERVIEWER

What sort of luck were you having getting the poems published?

WILSON

It was early on in 1965 when I wrote some of my first poems. I sent a poem to Harper’s magazine because they paid a dollar a line. I had an eighteenline poem and just as I was putting it into the envelope, I stopped and decided to make it a thirtysixline poem. It seemed like the poem came back the next day, no letter, nothing. “Oh” I said to myself, “I see this is serious. I’m going to have to learn how to write a poem.”

INTERVIEWER

What was your first play in which characters talked to each other?

WILSON

In 1977 I wrote a series of poems about a character, Black Bart, a former cattle rustler turned alchemist. A good friend, Claude Purdy, who is a stage director, suggested I turn the poems into a play. He kept after me, and not knowing any better I sat down from one Sunday to the next and wrote a 137page, singlespaced musical satire called Black Bart and the Sacred Hills. Claude started taking it around to theaters and Lou Bellamy at Penumbra Theatre in St. Paul produced it in 1981. It ended up being my first professional production. I had moved to St. Paul in 1978 and got a job at the Science Museum of Minnesota writing scripts—adapting tales from the Northwest Native Americans for a group of actors attached to the anthropology department. So I began work in the script form almost without knowing it. In 1980 I sent a play, Jitney, to the Playwrights’ Center in Minneapolis, won a Jerome Fellowship and found myself sitting in a room with sixteen playwrights. I remember looking around and thinking that since I was sitting there, I must be a playwright too. It was then that I began to think of myself as a playwright, which is absolutely crucial to the work. It is important to claim it. I had worked so hard to earn the title “poet” that it was hard for me to give it up. All I ever wanted was “August Wilson, poet.” So the idea of being a playwright took some adjusting to. I still write poetry and think it is the highest form of literature. But I don’t call myself a poetplaywright. I think one of them is enough weight to carry around.

INTERVIEWER

Would an audience recognize those early works as yours?

WILSON

My early attempts at writing plays, which are very poetic, did not use the language that I work in now. I didn’t recognize the poetry in the everyday language of black America. I thought I had to change it to create art. I had a scene in a very early play, The Coldest Day of the Year, between an old man and an old woman sitting on a park bench. The old man walks up and he says, “Our lives are frozen in the deepest heat and spiritual turbulence.” She looks at him. He goes on, “Terror hangs over the night like a hawk.” Then he says, “The wind bites at your tits.” He gives her his coat. “Allow me, Madam, my coat. It is made of the wool of a sacrificial lamb.” “What’s that you say?” she says, “It sounded bitter.” He says, “But not as bitter as you are lovely . . . as a jay bird on a spring day.” Very different from what I’m writing now.

INTERVIEWER

How do you look back on those early efforts?

WILSON

They had validity. I was exploring the same themes as I do now, but in a different language. It turns out I didn’t have to do it that way.

INTERVIEWER

What have been your influences?

WILSON

My influences have been what I call my four Bs—the primary one being the blues, then Borges, Baraka, and Bearden. From Borges, those wonderful gaucho stories from which I learned that you can be specific as to a time and place and culture and still have the work resonate with the universal themes of love, honor, duty, betrayal, etcetera. From Amiri Baraka I learned that all art is political, though I don’t write political plays. That’s not what I’m about. From Romare Bearden I learned that the fullness and richness of everyday ritual life can be rendered without compromise or sentimentality. To those four Bs I could add two more, Bullins and Baldwin. Ed Bullins is a playwright with a serious body of work, much of it produced in the sixties and seventies. It was with Bullins’s work that I first discovered someone writing plays about blacks with an uncompromising honesty and creating rich and memorable characters. And then James Baldwin, in particular his call for a “profound articulation of the black tradition,” which he defined as “that field of manners and rituals of intercourse that can sustain a man once he’s left his father’s house.” I thought, Let me answer the call. A profound articulation, but let’s worry about the profundities later. I wanted to put that on stage, to demonstrate that the “manners and rituals” existed and that the tradition was capable of sustaining you.

INTERVIEWER

And from mainstream theater?

WILSON

Everything I could or can. While I certainly recognize that there are other forms, other approaches to theater, African ritual theater and Japanese Kabuki theater, for example, the theater that I know and embrace is essentially a European art form—the ageold dramaturgy handed down by the Greeks and rooted in Aristotle’s Poetics. I bring an AfricanAmerican cultural sensibility to that art form and try to infuse it with the principles of aesthetic statement culled from a variety of sources, but primarily—as I was saying—from the great literature of the blues.

INTERVIEWER

Can you speak about Romare Bearden and what drew you to his work?

WILSON

I first came across his work in 1977 in a book called The Prevalence of Ritual—representations of black life in the ritualistic terms Baldwin was speaking of . . . street scenes, home life, weddings, funerals. One of the things that impressed me was that it lacked the sentimentality that one might have expected, but it was exciting and rich and fresh and full. When asked about his work Bearden said, “I try and explore, in terms of the life I know best, those things which are common to all cultures.” The life I know best is black American life and through Bearden I realized that you could arrive at the universal through the specific. Every artist worth his salt has a painting of a woman bathing. So Bearden’s Harlem Woman Bathing in Her Kitchen is no different as a subject than you would find in Degas, but it is informed by African-American culture and aesthetics.

INTERVIEWER

Is it a concern to effect social change with your plays?

WILSON

I don’t write particularly to effect social change. I believe writing can do that, but that’s not why I write. I work as an artist. All art is political in the sense that it serves someone’s politics. Here in America whites have a particular view of blacks. I think my plays offer them a different way to look at black Americans. For instance, in Fences they see a garbage man, a person they don’t really look at, although they see a garbage man every day. By looking at Troy’s life, white people find out that the content of this black garbage man’s life is affected by the same things—love, honor, beauty, betrayal, duty. Recognizing that these things are as much part of his life as theirs can affect how they think about and deal with black people in their lives.

INTERVIEWER

How would that same play, Fences, affect a black audience?

WILSON

Blacks see the content of their lives being elevated into art. They don’t always know that it is possible, and it’s important for them to know that.

INTERVIEWER

Are you worried that aspects of black culture are disappearing?

WILSON

No, I find the culture robust, but I worry about a break in its traditions. I find it interesting that in the convocation ceremonies of the historically black colleges that I have attended they don’t sing gospel, they sing Bach instead. It’s in the areas of jazz and rap music that I find the strongest connection and celebration of black aesthetics and tradition. My older daughter called me from college, all excited, and said, “Daddy, I’ve joined the Black Action Society and we’re studying Timbuktu.” I said, “Good, but why don’t you study your grandmother and work back to Timbuktu? You can’t make this leap over there to those African kingdoms without understanding who you are. You don’t have to go to Africa to be an African. Africa is right here in the southern part of the United States. It’s our ancestral homeland. You don’t need to make that leap across the ocean.”

INTERVIEWER

You speak of your early plays as being poetic. What caused the change?

WILSON

When I first started writing plays I couldn’t write good dialogue because I didn’t respect how black people talked. I thought that in order to make art out of their dialogue I had to change it, make it into something different. Once I learned to value and respect my characters, I could really hear them. I let them start talking. The important thing is not to censor them. What they are talking about may not seem to have anything to do with what you as a writer are writing about but it does. Let them talk and it will connect, because you as a writer will make it connect. The more my characters talk, the more I find out about them. So I encourage them. I tell them, Tell me more. I just write it down and it starts to make connections. When I was writing The Piano Lesson, Boy Willie suddenly announced that Sutter fell in the well. That was news to me. I had no idea who Sutter was or why he fell in the well. You have to let your characters talk for a while, trust them to do it and have the confidence that later you can shape the material.

INTERVIEWER

It’s interesting that you started with poetic drama, because you have such a wonderful ear for dialogue.

WILSON

The language is defined by those who speak it. There’s a place in Pittsburgh called Pat’s Place, a cigar store, which I read about in Claude McKay’s Home of Harlem. It was where the railroad porters would congregate and tell stories. I thought, Hey, I know Pat’s Place. I literally ran there. I was twentyone at the time and had no idea I was going to write about it. I wasn’t keeping notes. But I loved listening to them. One of the exchanges I heard made it into Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom. Someone said, “I came to Pittsburgh in ’42 on the B & O,” and another guy said, “Oh no, you ain’t come to Pittsburgh in ‘42 . . . the B & O Railroad didn’t stop in Pittsburgh in ‘42!” And the first guy would say, “You gonna tell me what railroad I came in on?” “Hell yeah I’m gonna tell you the truth!” Then someone would walk in and they’d say, “Hey, Philmore! The B & O Railroad stop here in ‘42?” People would drift in and they’d all have various answers to that. They would argue about how far away the moon was. They’d say. “Man, the moon a million miles away.” They called me Youngblood. They’d say, “Hey, Youngblood, how far the moon?” And I’d say, “150,000 miles,” and they’d say, “That boy don’t know nothing! The moon’s a million miles.” I just loved to hang around those old guys—you got philosophy about life, what a man is, what his duties, his responsibilities are. . . . Occasionally these guys would die and I would pay my respects. There’d be a message on a blackboard they kept in Pat’s Place: “Funeral for Jo Boy, Saturday, one p.m.” I’d look around and try to figure out which one was missing. I’d go across to the funeral home and look at him and I’d go, “Oh, it was that guy, the guy that wore the little brown hat all the time.” I used to hang around Pat’s Place through my twenties, going there less as the time went by. That’s where I learned how black people talk.

INTERVIEWER

Did they know you were interested in writing?

WILSON

No, but someone around the neighborhood must have guessed. One day there was a knock at the door of the rooming house where I was living. This guy was standing there. “They said you would buy this from me?” He had this typewriter. I knew he had stolen it and couldn’t find anyone to sell it to. If he’d stolen a TV, he could have quickly sold it to anybody. So he was mad as hell walking around trying to sell this thing that in the black community had no market value. But somebody had sent him to my house, telling him, “This guy has books and papers and stuff. Maybe he’ll want to buy it.” So I said to him, “How much do you want for it?” He said, “Give me ten dollars.” I happened to have ten dollars and I didn’t have a typewriter. So I gave him ten dollars. Because it wasn’t an extra ten dollars and I needed ten dollars to get through the week, I took the typewriter and pawned it. When I had enough money to spare, eleven dollars and twentyfive cents, I went to the pawnshop and got it back out—the $1.25 to the pawnbroker. I was eternally grateful. I kept that typewriter for ten years. We played the game many times. When I’d get into a jam I’d take it back to the pawnshop.

INTERVIEWER

You once said that you write a lot in bars and restaurants. Do you keep to this?

WILSON

I write at home now more than I’ve done before. I started writing poetry when I was twenty years old; you cannot sit at home as a twentyyearold poet. You don’t know anything about life. At that time many of my friends were painters and when I’d go visit them, I’d hear them complaining about needing money to buy paint. I recall visiting a painter friend of mine who was frustrated because he didn’t have the three dollars to buy a tube of yellow paint. When I pointed to some yellow paint on his pallet he said, “Naw, man, I’m talking about chrome yellow.” Then I realized how lucky I was because my tools were simple—I could borrow a pencil or paper; I could write on napkins or paper bags. I’d walk around with a pen or pencil and I’d discover poems everywhere. I was always prepared to write. Once when I was writing on a paper napkin, the waitress asked, “Do you write on napkins because it doesn’t count?” It had never occurred to me that writing on a napkin frees me up. If I pull out a tablet, I’m saying, “Now I’m writing,” and I become more conscious of being a writer. The waitress saw it; I didn’t recognize it, she did. That’s why I like to write on napkins. Then I go home to another kind of work—taking what I’ve written on napkins in bars and restaurants and typing it up, rewriting.

INTERVIEWER

Has the process changed over the years?

WILSON

My writing process is more or less the same. But I haven’t found a place in Seattle where I’m comfortable writing. I went to this one place where there must have been fourteen people sitting around writing. I thought, I’ve found the place where writers come. I sat there and waited but nothing came. I thought, These other people are taking all the writing stuff in the air for themselves, they’re taking it all away. Afterwards I made this joke about how my muse got into an argument with someone else’s muse and had been thrown out of the restaurant. That was why I was sitting there waiting with nothing happening.

INTERVIEWER

If you are not writing in restaurants, where do you work?

WILSON

I work in the basement of my house. On some days it is a sanctuary. On others it’s a battlefield and then at times it’s a dungeon. It is a place surrounded by the familiar particulars of my life. Photographs, yellow tablets, pens, books, music. I used to have a punching bag, but as I got older I traded it in for a chair. I work at a standup desk, which allows me to pace around. I have quotes, no more than two or three, that I use to keep me focused and inspired. For my new play, King Hedley II, Ihad a quote by Frank Gehry on his plans for the Corcoran Gallery addition—I hope to take it to the moon. And a quote attributed to Charlie Parker—Don’t be afraid. Just play the music. And from the Bhagavad Gita—You have the right to the work but not the reward. Other than that, I’m on my own.

INTERVIEWER

Can you say something about your work habits there?

WILSON

I write in longhand, usually on a yellow pad. I write in spurts, an explosion of writing activity that is part of a longer sustained concentration. These spurts generally last twenty minutes. When I’m working on a play, I maintain focus until the next burst of activity. It is an intense and sometimes furious activity. To find yourself there at that moment, in a way that you will never be again, is full of what I call “tremor and trust.” I’ve discovered that I work essentially in collage. Being an admirer of Romare Bearden’s collages, I try to make my plays the equal of his canvases. In creating plays I often use the image of a stewing pot in which I toss various things that I’m going to make use of—a black cat, a garden, a bicycle, a man with a scar on his face, a pregnant woman, a man with a gun. Then I assemble the pieces into a cohesive whole guided by history and anthropology and architecture and my own sense of aesthetic statement.

INTERVIEWER

How about rituals? Any to get you going?

WILSON

I always approach my work with clean hands. I will do a symbolic cleansing with my morning coffee, if nothing else is available. I do a lot of mental and spiritual preparation for what is essentially a journey on which I am going to make discoveries about myself and the nature of human life. It can sometimes be a painful process. I have a character who says, “Life without pain ain’t worth living.” So I’m willing to accept that. There’s an awful lot of joy also. I accept that. I had dinner with Charles Johnson, the novelist, who is a Buddhist, and he was quoting his favorite passage from the Bhagavad Gita, the quote I mentioned before, which says that you have the right to the work but not the reward. I just love that. It says something I’ve always felt—that I’m not entitled to anything other that the work. Which is sufficient—a joy unto itself. I feel it a privilege to stand at the edge of the art having been gifted with the triumphs and failures of countless playwrights down through the ages. It’s a privilege I don’t want to squander.

INTERVIEWER

Can you talk about the genesis of a work? The Piano Lesson?

WILSON

I started with the idea from one of Romare Bearden’s paintings—The Piano Lesson, the subtitle of which was Homage to Mary Lou Williams, who was a jazz pianist in Pittsburgh. I started with a question—Can you acquire a sense of self worth by denying your past, or is implicit in that denial a repudiation of the worth of the self? Once deciding that, I had to construct a series of events that posed that question and illustrated some possible answers. I started by having four guys carry the piano into the house. I wrote eight pages of dialogue that went like this—“Turn it around the other way.” “Move it up on that end.” “Watch yourself!” “Come on now, lift up on that end.” Once they got it in the house they began arguing about where to put it. I thought, Wait a minute, where am I going? What am I doing? So I threw those pages out and started over. And then I got the idea of the brother coming into the house like a tornado, bringing in the past that his sister is trying to deny. I usually start with a line of dialogue, which contains elements of the plot, character, and the thematic idea. For instance, I started Two Trains Running—“When I left out of Jackson I said I was gonna buy me a V-8 Ford and drive by Mr. Henry Ford’s house and honk the horn. If anybody come to the window I was gonna wave. Then I was going out and buy me a 30.06, come on back to Jackson and drive up to Mr. Stovall’s house and honk the horn. Only this time I wasn’t waving.” That contains the attitude of the character, his approach to the world, and contributes to what became an important element of the play. So I ask myself, Who is talking? Who is he talking to? Who is Stovall? Why does he want to get a gun and go see him, etcetera. In answering the questions the play begins to emerge. Eventually I name the character, decide on a setting, and begin to construct the play in earnest.

INTERVIEWER

Is there a gestation period?

WILSON

Yes. When I finish a play, after I type “The End,” I immediately begin work on the next play. I force myself to sit there until I come up with something, an idea, a title, a character, a line of dialogue, etcetera. That way I’m always working on something. So if you ask me ten minutes after I finish a play what I’m working on, I’ll be able to tell you I’m working on a new play. That begins the gestation period. It can be anywhere from two months to two years. It is difficult sometimes, given the responsibility of public life, to find a block of time in which to do the work. The gestation period has become increasingly longer, which I think is ultimately good for the work.

INTERVIEWER

What areas of playwriting give you the most trouble?

WILSON

I would say the management of time. That has always been a problem. For instance, in King Hedley II, I have a character who plants some seeds in one scene. The way the play is structured they have to be growing in the next scene. There is not enough time for this to be realistic, so you have to ask the audience to make a leap of faith, suspend disbelief and accept that the seeds are growing. Things of that sort I have not always managed well.

INTERVIEWER

What is easiest?

WILSON

The characters and their dialogue. The characters want to explain, as most people do, their entire history and philosophy, their take on the world and the vagaries of life. Sékou Touré has said that language describes the idea of the one who speaks it. I discovered that what is easiest for me, once I know who is speaking, is to translate the ideas and attitudes that I find in the blues into a language that defines and illuminates the characters, along with the elements of their philosophies and attitudes that are central to the play’s thematic concerns.

INTERVIEWER

Is there a character who is a particular favorite?

WILSON

I like all my characters and I’ve always said that I’d like to put them all in the same play—Troy and Boy Willie and Loomis and Sterling and Floyd. I once wrote this short story called “The Best Blues Singer in the World,” and it went like this—“The streets that Balboa walked were his own private ocean, and Balboa was drowning.” End of story. That says it all. Nothing else to say. I’ve been rewriting that same story over and over again. All my plays are rewriting that same story. I’m not sure what it means, other than life is hard.

INTERVIEWER

How important is plot to you?

WILSON

Obviously if you are going to write good plays they have to be plotted. Plot is an essential tool of the dramatist. But in the way my plays are structured, plot grows out of characterization. The play doesn’t flow from plot point to plot point. It emerges from the seemingly pointless banter of the characters. If you dismiss the banter as so much excessive verbiage, then you can miss the plot. In Seven Guitars you hear four men talking and you may think the play is not going anywhere. They are sitting in the yard reciting childhood rhymes, and it might seem that the rhymes are simply entertainment and do not contribute and advance the plot. But they do. Everything in the plays connects to something and is designed to lend resonance and support for the ideas and action of the play.

INTERVIEWER

How much does the direction of a play change as it progresses? Do you keep a tight rein on things?

WILSON

It varies. I always say if it doesn’t change, you’re not writing deep enough. I make discoveries as I go along. Sometimes the direction of the play can change dramatically. As far as keeping a tight rein, sometimes you just let go; sometimes your passion can carry you to places where you lose control and then something exciting happens—the characters forge their own way. Hedky in Seven Guitars, for example, assumed a much larger presence than I had originally imagined. He ended the first act, and I was surprised to find him on stage alone at the start of the second act. He demanded that I focus on him and what he had to say. He was a most unruly character. He threatened to knock down the set and remake the world to his liking. In times like that you have to reassert your authorial control.

INTERVIEWER

Is it easy to divide a work? Do you pick a dramatic closing scene and then back into it?

WILSON

I often come up with my firstact curtain early on. I look for a defining moment in the character’s life that also, in large part, defines the play. In King Hedley II, for instance, before I knew much else about the play I knew that someone was going to step on some seeds that a character had planted and that the character was going to go berserk . . . which could be my act break.

INTERVIEWER

How much can you produce in a day’s work?

WILSON

Sometimes nothing. Writing ideally is recognizing your bad writing. I mean, people ask if I write bad lines, and I say, Man, I write bad scenes! I put them in a drawer where nobody can see them.

INTERVIEWER

How much revision is necessary?

WILSON

It varies. But I’m a strong believer in rewrites. Rewrites are the shaping of the material you have already processed. It is an essential part of the work. The process of shaping may lead to discoveries and it may be necessary to climb back into the heat of the moment. I often make references to my notes during rewrites. They are a record of the germination of the work; sometimes contained in there is a crucial idea which you have strayed from. In architectural terms, I walk around and test the structure to make sure there is support for the ideas of the play and its validity as a work of art.

INTERVIEWER

Do you write with a particular audience in mind?

WILSON

No more than, say, Picasso painted with a particular audience in mind. The nature of the audience is built into the craft of playwriting, of course, but that’s not the same as writing for a particular audience. I write to create a work of art, to contribute to the art form and to make my aesthetic statements.

INTERVIEWER

Does it bother you that your audiences are mostly white?

WILSON

I don’t think about it. Here again, to go back to Picasso, you create the work to add to the artistic storehouse of the world, to exalt and celebrate a common humanity. I don’t think Picasso thought too much about whether the viewers of his paintings were French or American or Asian or German. I think the primary concern is to do the work to the best of your ability and to fulfill its aesthetic requirements. My audience, if I thought of one, would be Ibsen, O’Neill, Miller, Williams, Baraka, and Bullins—my fellow playwrights who have wrestled with the problems of the an form and have contributed to my understanding of it. When I sit down to write, I am sitting in the same chair that Ibsen sat in, that Brecht, Tennessee Williams, and Arthur Miller sat in. I am confronted with the same problems of how to get a character on stage, how to shape the scenes to get maximum impact. I feel empowered by the chair. For years I sat in that chair and tried to best my predecessors, to write the best play that’s ever been written. That was my goal until I ran across a quote by Frank Lloyd Wright, who said he didn’t want to be the best architect who ever lived. He wanted to be the best architect who was ever going to live. That added fuel to the fire and raised the stakes, so to speak. Now you’re not only doing battle with your predecessors but with your successors as well. It drives you to write above your talent. And I know that’s possible to do because you can write beneath it.

INTERVIEWER

While white audiences can enjoy black music—jazz, blues, soul—is black theater something of a stretch for them?

WILSON

The question I can answer is whether—as a black audience member—theater based on white experience is something of a stretch for me. Can I appreciate the work of Ibsen, Chekhov, Miller, Mamet? The answer, of course, is yes, because the plays ultimately are about things I am familiar with—love, honor, duty, betrayal . . . the same way, for instance, I can appreciate German or Italian opera though I don’t speak the language . . . I can appreciate good singing and dramatic incident the same way I can appreciate Wynton Marsalis, Skip James, or Bukka White. I would think the white members of the audience can appreciate my plays because the specifics and the social manners of the characters, while they may be different, can certainly be recognized as part of human conduct and endeavor.

INTERVIEWER

Do you often go to the theater?

WILSON

I don’t go to the theater very much. Nor the movies. I didn’t go into a movie theater for eleven years. I read the reviews and I try to keep up with what is going on. But in the evenings I play with my twoyearold daughter. I don’t watch TV. I read. I listen to music. I have a large collection—classical, jazz, Eastern Arab, Irish—all kinds of stuff. I have a large blues collection, probably the largest section of what I have, much larger than jazz because the blues have words. I’ve never heard a piece of music I didn’t like.

INTERVIEWER

Do you try out the plays on your family?

WILSON

My first critic is my wife. But it’s better to get people who are not involved in the theater, who have no preconceived ideas against which they can measure what they’re seeing. My favorite critic is my brother, who has no particular interest in the theater. He’ll let you know exactly what he thinks.

INTERVIEWER

What are your notions about the importance of production? Edward Albee has said that “A firstrate play exists completely on the page and is never improved by production; it is only proved by production.” Would you agree?

WILSON

I agree with that. I don’t write for a production. I write for the page, just as I would with a poem. A play exists on the page even if no one ever reads it aloud. I don’t mean to underestimate a good production with actors embodying the characters, but depending on the readers’ imagination they may get more by reading the play than by seeing a weak production.

INTERVIEWER

What kind of liberties do directors take with your plays?

WILSON

I like it when directors try different things, even though they don’t always work. I don’t want to see a production that’s a near duplicate of the original. One production of Ma Rainey had a spiritual dancer in it. I personally didn’t think it worked, but I didn’t mind them trying it out. What I objected to was listing the spiritual dancer in the cast as if that dancer was part of my script. Another production had Hambone after he died coming back dressed in a white suit and looking in the window of the restaurant. The audience loved seeing this homeless person dressed in an elegant white suit. I wouldn’t have done that if I were directing the play, but it worked for the audience.

INTERVIEWER

Do you go to opening nights?

WILSON

Yes. I go to opening nights and sit in the audience. But the performance that I look forward to and enjoy best is the very first time the play ever plays before an audience. There is nothing quite like that. That’s the most honest collaboration between actor and audience that you’re ever going to get. It’s before the review, before the word of mouth; it’s that moment of actuality when no one, actors or audience, knows what is going to happen next.

INTERVIEWER

What do you see as the essential element to be established in the drama?

WILSON

I see conflict at the center. What you do is set up a character who has certain beliefs and you establish a situation where those beliefs are challenged and the character is forced to examine those beliefs and, perhaps, changes. That’s the kind of dramatic situation which engages an audience, forces them to go through the same inner struggle. When I teach my workshops I tell my students if a guy announces, “I’m going to kill Joe,” and there’s a knock on the door, the audience is going to want to know if that’s Joe and why this guy wants to kill him and whether we would also want to kill him if we were in the same situation. The audience is engaged in the question.

INTERVIEWER

Are there other techniques, tricks that you suggest in your students’ workshops?

WILSON

After we talk about what a play is, I ask them to invent a painting in their minds and then describe it in words.

INTERVIEWER

That frees them up?

WILSON

Absolutely. If you tell them to write a description, they get too conscious and can’t do it. Let me give you an example—in his word-painting a guy will describe a train station. He says, “There’s a woman wearing a white dress over there and some guys sitting in another part of the station.” Then I start asking questions. “Is she coming or is she going?” “Going.” “Where is she going?” “To visit her grandmother.” And simply by asking these quesitons we find out who this person is. Then we’ll find out about these guys over in the other part of the station. All of a sudden the student yells, “I can write a play about this!” You’ve caught him by surprise. Until he began fleshing out the painting, he didn’t even know who the woman was.

INTERVIEWER

This wordpainting technique sounds a little like your napkin writing.

WILSON

Well, it’s about changing their approach. I tell them anybody can write a play, just like anybody can drive a car. All of us can learn the rules of the road, make the turns, switch on the lights. But there is Mario Andretti out there. I can’t make them into Mario Andretti, obviously. But they know I’ve never taken a playwriting class or read any books about it. Everything I know comes from my own writing. Those students, many of whom came back for those three years I taught, really did become better playwrights; a couple of them even had productions of their plays produced. I quit teaching after the three years. But after I finish these three plays I have in mind, and the novel, I think I’d like to go back to it. But first, I’ve got to finish those plays. That’s first.

INTERVIEWER

If you hadn’t found the theater, what do you think you might have done?

WILSON

I don’t know. I probably would have become a novelist. The only thing I know for sure is that I would have been involved in what Borges called “the problematic practice of literature.” I fell in love with words as concretized thought when I was a kid and knew somehow that I would spend my life involved with them. I probably would have pursued my poetry with more resolve and more purpose. I remember when I was twenty years old and the world was wide open as to how I was going to live my life and make a contribution, to mark my passing, as it were. I had fallen in with a group of painters. I was intrigued and fascinated with the idea of painting. I didn’t question whether I had any talent for it. In my youthful arrogance and exuberance I felt I could do anything.

INTERVIEWER

Do you see advantages in the novel form?

WILSON

The big difference in writing a novel is that the narrator can take an audience to places you can’t on a stage. What I can do in a novel is to take you down this dusty road and have you taste the dust. Suddenly it gets dark and two million crows come flying across going south. They black out the sun. I can’t do that on stage. But in a novel I can make you see those crows and have that mean something. I’ve got about sixty pages of a novel. Notes. A page here, an idea there. It really wants to be born. On occasion I have dinner with Charles Johnson, and every time I tell him I want to write a novel but that I don’t know how to do it. I can’t see the form of a novel—this vast ocean where I really don’t know how to get from here to there. I tell him that for me writing a novel is like being on an ocean without a compass. And he says, “Well, go find a compass!” So I guess that’s what I have to do. As soon as I find a compass I’ll take a shot at it.

INTERVIEWER

Isn’t a “compass” necessary in the writing of a play?

WILSON

For me a play is more like a river that you can navigate . . . a big bend there, a tree by the shore.

INTERVIEWER

If you had to construct an imaginary playwright, with what qualities would you endow him or her?

WILSON

Honesty. Something to say and the courage to say it. The will and daring to accomplish great art. Craft. Craft is what makes the will and dating work and allows playwrights to shout or whisper as they choose. A painter who has not mastered line and form, mass, perspective and proportion, who does not understand the values and properties of color, is not going to produce interesting paintings no matter the weight and measure of his heart, or the speed and power of his intellect. I don’t think you can ever know too much about craft. So I would give your imaginary playwright a solid understanding of craft. All that is necessary then is ambition . . . which is as valid and valuable as anything else.

(additional material by Bonnie Lyons)

>via: http://www.theparisreview.org/interviews/839/the-art-of-theater-no-14-august-wilson