How I Got Up

After Being Cut Down

Chester Burnett was a bear of a man. He would shake his huge frame and women would scream and shout. Plus, quite a few men would moan and groan as they sang along to the familiar but none-the-less enthralling lyrics that Wolf would be bellowing.

Howlin’ Wolf was Burnett’s stage name, especially up Chicago way in the mid-sixties when he, Muddy Waters, and a whole passel of blues magicians were plying their trade in the Windy City.

Wolf’s iconic song “Killing Floor”, which was recorded on Chess Records in 1964 but written much earlier, had a subtext that the audience knew well but which might easily escape the understanding of non-followers who were not steeped in the vernacular. Besides being hard and bloody, working in the slaughter houses was psychologically taxing on the under-paid labor whose job it was to end the lives of cows and pigs in order to prepare choice cuts of beef and pork.

The underlying meaning of the song referred to being cut down, feeling so low that one felt like one was getting kilt on that dirty, slimy flo’. Your guts cut out and viscera spilling forth from your carcass that had been split open from throat to genitals. Your mind had to be right and your constitution rock solid to keep on doing that spirit sapping work day after day.

When Wolf’s compatriot Muddy Waters sang “I’m A Mannnn” he was partly referring to being strong enough to withstand the trials, tribulations, toils and troubles of working on the killing floor.

# # #

On the sixth of March 2022, I found myself down on a personal killing floor.

I got up about 3:30am that Sunday morning, headed across the apartment from my bed beside the back wall, to the toilet at the other end of the second floor space. When I finished my business, to my utter surprise I could not rise off the commode. My legs simply wouldn’t work.

I waited a little longer and tried again. Nada. Waited awhile more. Tried a third time. Again, no go. After a time period hoping to wait out the problem, I tried and failed again. My legs didn’t hurt, they just wouldn’t work. I don’t know how long I sat there unable to move. The wound care specialist estimates, based on the breakdown of the skin on my butt, I must have been immobile for at least an hour or more.

I vowed to myself. I’m not going out like this. So, I used my right arm, leaned against the bathtub and lowered myself to the floor. My intention was to crawl out of the bathroom. Or so I thought. But, being a good negro, the first thing I did when I stretched out on the floor, I fell fast asleep.

When I awoke an indeterminate time later, to my dismay I discovered that I could not even crawl away.

I’m a veteran. I had crawled fifty yards during night training, with a rifle cradled in my arms, Iive machine gun fire streaming above my head. I was not afraid. Discovering my partial paralysis did not dismay me. I couldn’t move but I never thought I was going to die.

I could faintly hear people conversing with each other as they passed in the hallway outside my apartment but they couldn’t hear me. So I lay there waiting for I didn’t know what. At some point, night fell and I was still stuck.

Long story short, I lay there all of Sunday and then came Monday morning. Still no go. I could no longer even guess what time it was.

Some time later I hear someone coming into the apartment. It was Ed, our maintenance man. He had a key. Along with an assistant he was searching to see if a third floor leak was dripping through, into my space. Fortunately, no water had leaked down, but I was.

“Take me to VA.”

# # #

I thought I saw Oliver Thomas as I was loaded into the ambulance. Both he and I are from CTC–Cross The Canal, in the Lower Ninth Ward below the Industrial Canal. It’s roughly a twenty-square block area. A lot of families are interrelated plus people know each other. There is usually no more than two degrees of separation between kin, classmates, and neighbors.

Oliver is well known. A city councilman from District E who was widely considered to be a leading candidate for mayor. Over the years, Oliver and I got to know each other, especially after his incarceration. He was convicted on a bribery charge even though he didn’t vote on the issue referenced for the contract in question. He was not reticent with me in discussing his life story both as a college athlete and subsequently as a politician. We talked in some detail about the scandal that entrapped him–what he did and didn’t.

The arc of Oliver’s life story bends toward redemption. He was good before his downfall. Getting back up took a major effort of personal will and humility. Rather than hide from his situation, after Oliver was released, he participated in a theater production by the Anthony Bean Theater in the Carollton section of New Orleans. The production not only included a dramatic exposition of Oliver’s predicament, the show also featured Oliver playing himself.

Sometimes you have to be knocked low, in order to get up and walk tall. Anybody, indeed, almost everybody can easily step away from the straight and narrow, however, there is nothing easy about escaping the social and/or political death of being caught on one’s particular killing floor.

Oliver is a friend. I support him.

Even though there is not much I can physically do at this particular point in my life journey, nevertheless, whenever we are down is precisely when we can use a helping hand up–be it socially, economically, or physically.

As I was wheeled downstairs Monday afternoon, I’m on my back and see a small throng of people on the sidewalk. I took Oliver’s presence among them as a rainbow sign that everything was going to be alright–he came thru his walk across the valley of death. Now was my turn.

And then the ambulance doors closed.

# # #

Datia. Angelica. Emanuel. And a whole bevy of nurses and therapists, plus, of course, a battery of doctors. When I arrived in the emergency unit, I had no idea what was wrong, nor how long I would be in an incapacitated condition. As it turns out my recovery would take a lot longer than I expected or hoped for.

Datia was from New Orleans but sent her two children to better schools in a neighboring parish (county).

Angelica is of Cuban heritage–although she and her sister were born in the USA, most of her family was in Cuba and many of them didn’t desire to emigrate.

Emanuel is Haitian and in addition to working hard as a medical professional, he is also struggling to get visas for extended family members.

Those are just three of the nurses who cared for me. They are all of African heritage. None of them looks like what some people call foreign. Angelica is Latina but sounds like the average Black New Orleanian when she speaks. We are so diverse.

I believe the banter and laughter of the mostly Black nurses was therapeutic, especially when they were briefly all together during their shift changes. Hearing them made me, and probably other patients, feel better. They may not have been aware of how uplifting it was to experience their mirth. Although they had very little time just to chat, I sometimes would have conversations about current conditions and about their lives outside the hospital.

Socializing is a major aspect of being human. Being lonely and simultaneously in the midst of people is both psychologically debilitating and ultimately destructive. Fortunately, I never felt totally isolated from human contact. Indeed, I looked forward to mini-conversations as I got to know the house-keeping and nursing staff, and they, in turn, got to know me.

# # #

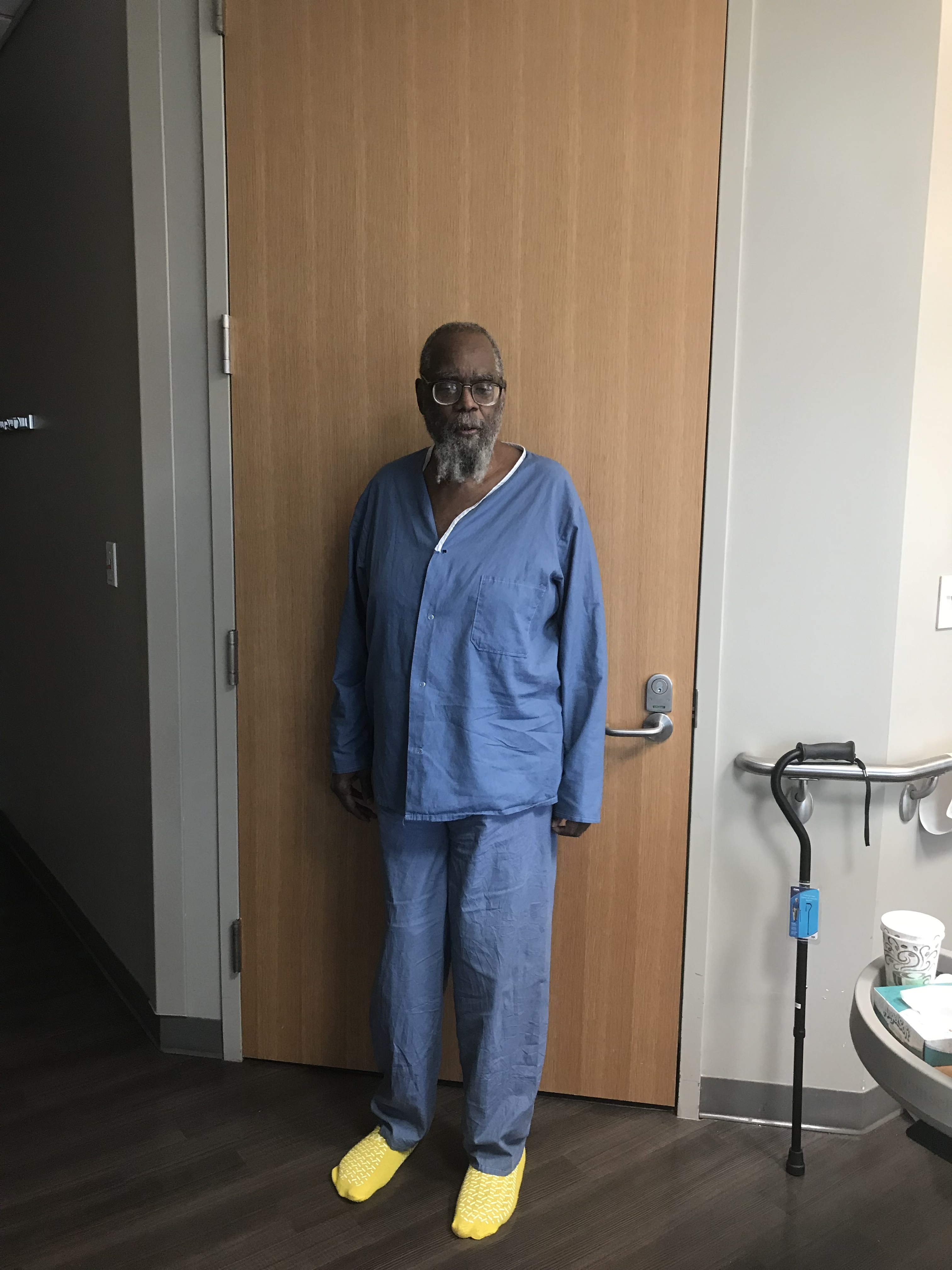

Looking back, by the end of the first week I could not only walk the hallway, but also slowly go up and down stairs. I thought I was ready to return home, but, slow your roll, buddy. You are not as ready as you might think.

During the second week of my stay I go through a battery of tests.

On that fateful Sunday morning, I must have sat on the commode a lot longer than I thought. I had a wound on my backside in a horse-shoe shape–actually the shape of the toilet seat. I was hoping to be discharged one week later, but that did not happen.

By the third week, bad news piled up day by day.

“That’s stupid,” my physician younger brother told me when I told him that I, along with my comrade Lionel McIntyre, had driven to Atlanta to see our terminally ill friend, Ed Brown, the older brother of Jamil El-Amin, aka H. Rap Brown.

We jump in a car about five in the morning and set out to Atlanta. When we arrived, we sat with Ed for about four hours, then rode straight back to New Orleans, arriving around midnight.

We had not stopped except for gas, and even then didn’t get out and walk around. Never thought about it.

Not even a week later, my right leg was hurting. I did not know what was happening. Eventually, I ended up in a hospital and was diagnosed with a blot clot. Untreated it could have taken me out. Fortunately, I was able to deal with the problem, relying largely on Wafarin, a blood thinner medication. I was told I would probably be on blood thinners for the rest of my life.

Ed made his transition about a week or so following our visit. That was in 2011. Eleven years later, I got the disconcerting news that the blood clots in my right leg were chronic–i.e. old and being managed, however I now had new blood clots in my left leg. That explained why I was having a pain under my left knee. The pain was so severe it was difficult to sleep at night.

I was routinely turning down the offers of Tylenol. Although I was assured that the pills weren’t an opiate, weren’t addictive. I didn’t want to become psychologically dependent on painkillers. I’m hard-headed, can even be ornery. Although the pain was very uncomfortable, I was pleased to know why I was hurting. Eventually, I relented and took doses of pain killers. However, as disconcerting as the blood clots were, there were other and more serious medical issues to deal with.

During the extensive tests I took, a life-threatening discovery was made. Following an MRI investigation during which I lay motionless, flat on my back, for over an hour in a tube, an early sign of cancer was revealed.

There was a spot on my pancreas that the doctors didn’t think was too troubling. On the other hand there was a small mass on one of my kidneys. The mass seemed to be cancerous although, thankfully, it had not yet metastasized.

A biopsy would be necessary to be absolutely sure that it was a growing cancer. The doctors were confident that the easiest and best solution was to cut out both the mass and the kidney–I didn’t need two kidneys to survive.

The complication was that in order to do an operation I needed to be stronger. Moreover, I also needed to be off of a blood thinner, otherwise there would be an increased danger of having an operation and subjecting myself to bleeding out. There was no easy decision.

After three weeks and still healing but far from fully functional, I had a possible opportunity to go to CLC. My daughter Tiaji, who lives in Maryland and works in the Congressional Research Department, came to visit me and checked out the conditions at an assisted living place where my now deceased, second wife, Beaula–bka “Nia”–was receiving care right before her third stroke.

Tiaji’s report was discouraging. Seems the facility was now under new management and no longer had a good reputation. I could possibly receive up to twenty-nine days under Medicare but after that I would have to pay the full costs myself. Additionally, they would not provide the level of wound care treatment I would receive at VA’s CLC.

Right before choosing either CLC or a private facility, I began to realize that I was much sicker than I initially thought. Full recovery would not be easy nor short. I had to get my mind right and settle into the reality that I was now 75-years-old–I celebrated that birthday in the hospital–well, not really celebrated. I did nothing special although I was served a large, sugar-icing ladened, maxi-sized cupcake, which I did not eat.

Much more difficult than a quick dash, getting well was going to be a long slog through weeks, rather than days, of treatment and therapy. Even though I had approached death, I remained anxious to get back to my usual activities.

At the end of the third week, there was the possibility of being moved to another and more isolating section of the Veterans Hospital: CLC (Community Living Center), which offered long term recuperation but had stringent visitation rules. No more gatherings of eight or ten people in my room. There was a real concern for the possibility of Covid transmissions. Plus, although we investigated a number of nursing homes, the reality was that VA isolation, including ongoing wound care, was the best choice.

One of the first people I meet is Asia Brumfield, who is a leading social worker in CLC. She recognizes my name and introduces herself. Turns out she is a former student when I was teaching high school with Students at the Center. I immediately notice that she wears her hair in Nubian knots and am both surprised and glad to see her.

Later, when my youngest daughter, Tiaji, arrives from Maryland to spend a week with her hospitalized father, it’s uplifting even though visitors have to run a major gauntlet to gain entrance. At one point Tiaji falls asleep in a big chair.

The oldest of five, my daughter Asante, who lives here in New Orleans, tells me that when she visits, the guard at the entrance responds when she says who she is coming to visit. “Tell him I said hello.”

Even though I don’t know everyone who visits, I am aware that the array of people who care runs the gamut from family to people I don’t know personally but who know of me as a result of my work in the community.

Moving into CLC convinces me that being here is significant. My room has a large bathroom with a shower, and a front space that includes a sink, faucet, and hygiene area. Were I not infirmed I would enjoy the amenities of being in CLC. I try to make the best of the situation but it’s not easy.

I could not see my backside even when I tried to examine my wounds in the large mirror in the bathroom. Moreover, and more importantly, I could not dress my own wounds. I needed help, preferably competent, professional care.

A complicating factor was the question of whether there was an available room in that housing section of the hospital. Fortunately, there was an available slot at CLC.

On my second-floor room in CLC, there was even an outside patio where one could sit and get some wonderful Vitamin D, which sunlight provides. Plus, I was receiving treatment from both physical and occupational therapists. I quickly realized I was much weaker and less able to care for myself than I wanted to believe.

After getting over to CLC, I was able to walk with the aid of a cane. Eventually, I did not require the cane to walk abound my spacious living quarters. I even could take an unassisted shower in the bathroom.

A hot shower was a high-point of my hospitalization. I had not washed myself the first week I was in-hospital, but at CLC, much to my delight, showering became an almost daily routine. Spraying myself with warm water felt really, really good. Being able to wash myself without the help of anyone made me feel a lot better.

# # #

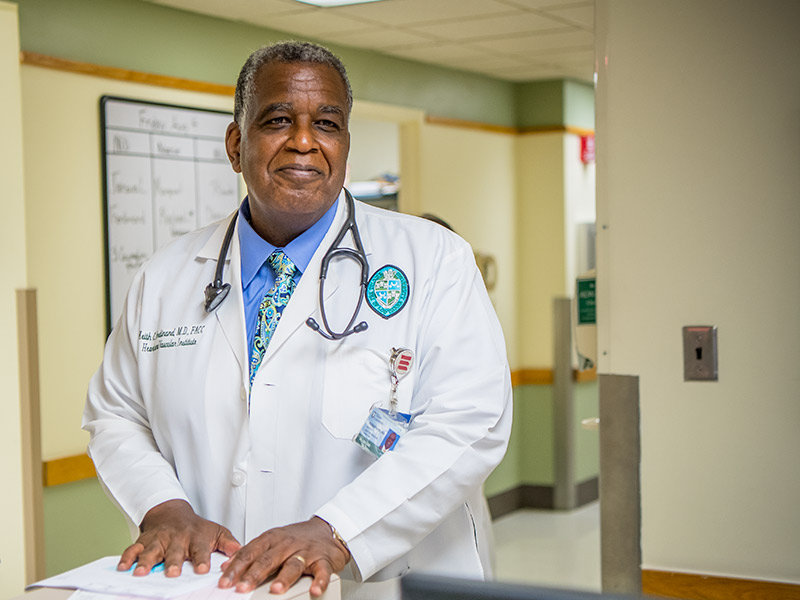

Pictured is Dr. Keith Ferdinand, a cardiologist and a professor of medicine at Tulane University School of Medicine’s Heart and Vascular Institute.

I knew I was blessed to have a respected physician as a younger brother. Keith not only gave me good advice, he was a knowledgable advocate who could talk that medical-mumbo-jumbo and thus was able to be an advocate who was also a sentinel observing the care I was receiving. Unfortunately, there was nothing he could do about the food service.

Fortunately, what was most beneficial was drinking water. The staff kept a large 30-oz cup full of crushed ice, so I had a generous supply of chilled water to consume on a regular basis, including the after-midnight hours. I can’t remember a time ever drinking as much water as I began to do in the hospital.

It is axiomatic that hospital food keeps you alive–but not all of it is high on tasty nutrition. Hospital diets are generally, at best, bland, particularly compared to well seasoned, salt and sugar heavy, typical New Orleans cuisine.

I purposely made a habit of not adding salt to my food. Scrambled eggs and grits were usually served for breakfast. It took a while for me to get used to the non-taste but I had concluded no added salt was better for me health wise. I even avoided adding margarine and Mrs. Dash as a condiment to my grits and eggs. No condiments was probably the hardest aspect to get used to.

Because I don’t eat red meat or poultry, resultantly I have baked Tilapia fish at lunch and for dinner. On Fridays I usually had the option of shrimp fettuccini, and once I even was served a cut of much enjoyed salmon.

To my delight, a desert of lemon meringue pie was served twice since being at CLC–that desert used to be my favorite as a youngster, moreover, I had not had any since before I went into the army in 1965. Although the pie was not good for my diet, I enjoyed every bite.

As I got used to the food, I also found myself acclimated to the size of the portions, which were much, much smaller than I usually prepared for myself. I not only ate less and loss weight, despite not doing any substantial amount of physical activity. I decided that, perhaps, once I was released I would actually cut back on the portions of food I prepared.

Every cloud has a lining. Every night, no matter how deep, inevitably gives way to dawn. Or death. Since I did not die, “I guess I’ll live another day.” Inevitably, whomever would hear me say that would smile.

# # #

Ms. Siney routinely took my food order for the day. She was both cheerful and helpful, and above all patient with me as we went through the menu, which was varied but not extensive. Her attitude and conviviality made the routine ordering process oftentimes as enjoyable, if not more so, than the meals themselves. Part of Siney’s beauty was her use of New Orleans colloquiums, or as she was wont to say: “All right, my baby,” with just the right speech inflections indicating we shared a common cultural orientation.

I love Black women. Far beyond racial hubris and heterosexual enchantment with a gender partner. Indeed, I am one who loves women the world over and simultaneously one who resists the urge to be either a dilettante or a predator. As my good friend Jimi Lee always encouraged, learn how to admire the garden without having to pick the flowers.

Among Black people it is axiomatic that Black women do all that they can to protect and love Black men, sometimes to our sister’s own detriment. Of course I know that not every woman feels that way. I know that there are women who have been scared and react with understandable hatred to males in general and especially to misogynistic male perpetrators. Moreover, such hatred is healthy–it is healthy to hate oppression and to resist those who oppress us. Nevertheless, my experience with a wide range of Black women teaches me that taken as a whole they love Black men way beyond what many of us deserve.

For Black women, such as Siney, and many others that I have encountered in life, as well as those who literally treat me in this hospital, loving Black men is an inseparable aspect of their DNA and daily practice. I would be either a fool or a monster if I did not acknowledge and try my best to mirror their essence.

Since being hospitalized, I now drink far more water than I previously did. The hospital does offer small 4-ounce servings of orange juice and apple juice with the daily meals. As far as I am concerned, the orange juice was too acidic to drink. The apple juice was ok but not much better than room-temperature water. The staff routinely filled a large, 30-ounce cup with ice, which over the course of a couple of hours offered satisfying sips of chilled water. The cup had a separate, Styrofoam outer sleeve that made handling the cup easy.

I had been encouraged to drink at least 64-ounces of water daily. Sometimes, I don’t imbibe as much as I should but I do much more than I previously had. At home I usually drank mango juice and fruit smoothies, which I prepared with a mixture of frozen fruit and juice blended together.

However, the food service was not a big issue; getting discharged was my goal.

# # #

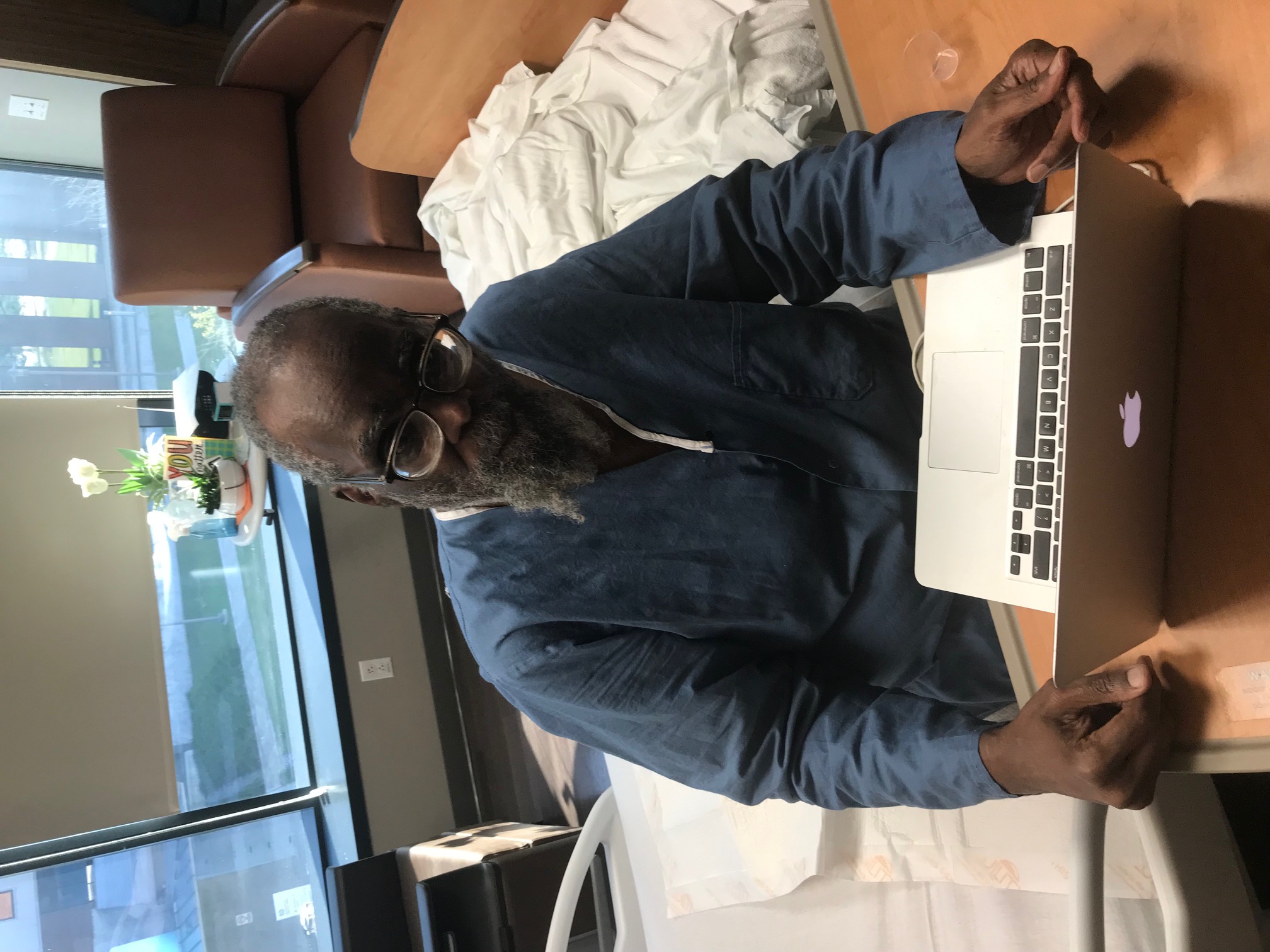

I have a major project that had a funding deadline.

The title of the project says it all: SEEING BLACK–Photography In New Orleans, 1840 and Beyond.

Photography began in France in 1839. In 1840 it was in New Orleans, brought here by Jules Lion. Lion was sometimes identified as a free man of color born in France but domiciled in New Orleans. He happened to be in France in 1839 and learned the new art of photography while there and subsequently brought photography back to New Orleans.

Circa 1958, I learned photography in seventh grade at Rivers Frederick Junior High School. I was introduced to photography by the industrial arts instructor, Mr. Conrad, who had constructed a darkroom in one of the storage closets and taught students after school. My first camera was a Yashica Twin Lens Reflex. I went around the school taking pictures. My nickname was “the picture man”.

However, I was introduced to Langston Hughes by my eighth grade English teacher, Mrs. O. E. Nelson. She said put your books away, I want you to hear something. Up until then, I voraciously read all kinds of books, some of which anthropomorphized the life stories of various mammals. Despite my wide ranging devouring of widely varying stories, I never cared for poetry. Langston Hughes turned me around.

On the recording Mrs. Nelson played for us, I remember Hughes recited his poetry backed by a jazz combo. The last lines of one poem in particular arrested my attention. It described a woman whose husband died suddenly and she went around Harlem begging for the money needed to give her man a fine burial. The concluding line of the poem asserted: “a poor man ain’t got no business to die.”

That was my magic moment. After school I went straight to the main library, asked the desk librarian where could I find a book by Langston Hughes. When I followed instructions, I expected to see a poetry book by Hughes, maybe even two. As I approached the designated shelf, I instead was confronted by multiple books, not only poetry but short stories, the then unknown to me collection of Semple stories, biographies about music and theatre, and much, much more. In my naivety I thought being a writer meant you had to be like Langston.

Hughes had two autobiographies: The Big Sea and I Wonder As I Wander. In those two books he mentioned a cornucopia of writers from all over the world. Every writer Hughes wrote about, I would seek their books, scan them quickly. If something they wrote struck me, I’d check out the book, if not I would return the book to the shelf. That was my literary higher education.

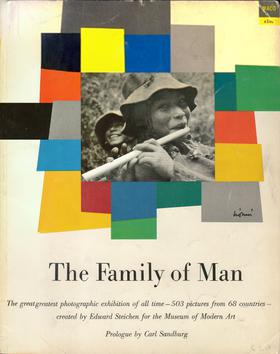

Additionally, because of my interest of photography, I stumbled across a major find, The Family Of Man, consisting of photographs from all around the world.

Unknowingly, I was schooled to see Black people as an integral part of the great flow of human history and did not elevate Whites above others.

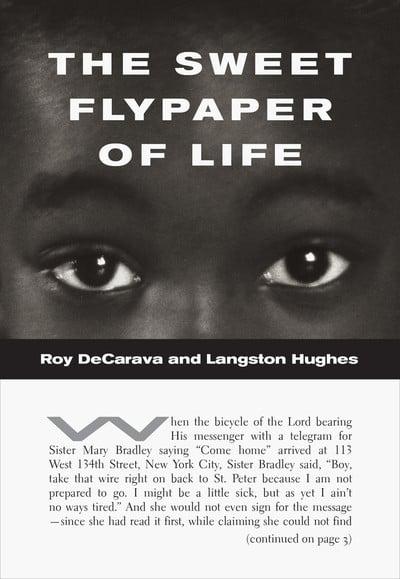

Hughes had done a book with photographer Roy DeCarava, The Sweet Flypaper Of Life. That cemented my life-long love affair with both photography and writing. Although generally thought of as a poet, Hughes wrote in all forms and genres. I assumed Hughes exemplified what being a writer meant and I modeled myself on Hughes.

While I kissed photography, I fell hard, head over heels, in love with writing. And though I subsequently won all kinds of awards and honors for writing, I never forgot that first kiss. One morning I woke up with an idea about photography. As the idea formalized, I knew I alone could not do it the way I wanted to do it. Eventually, I gathered a four-member team to do SEEING BLACK.

Our team consisted of professional photographers Eric Waters, with whom I attended high school, and Girard Mouton III, who was expert as both an archivist and investigative historian. Shana griffin was our business administrator handling and coordinating a myriad of moving parts. Shana’s associate, Renee Royale, later came aboard to supplement our founding quartet.

By the spring of 2022, with the help of friends, we had raised about $35,000.00 for the project–20K of which had to be spent by October 2022 or we would have to return money secured by the University of New Orleans Press. There was no time to delay or to hesitate. There was so much that remained to be done.

SEEING BLACK, featuring the work of historic and of contemporary Black photographers who are, or were, domiciled in New Orleans, was the focus of most of my attention.

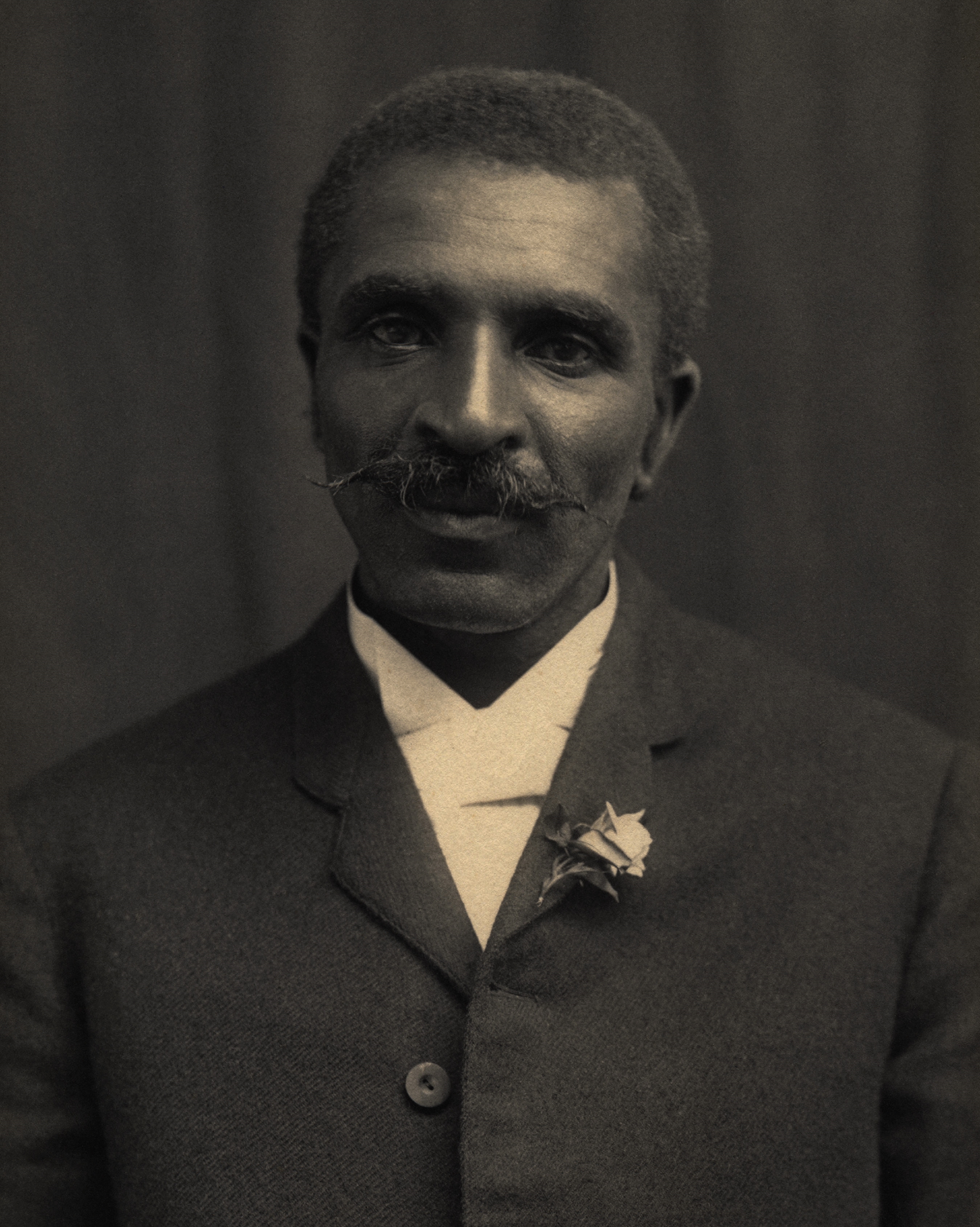

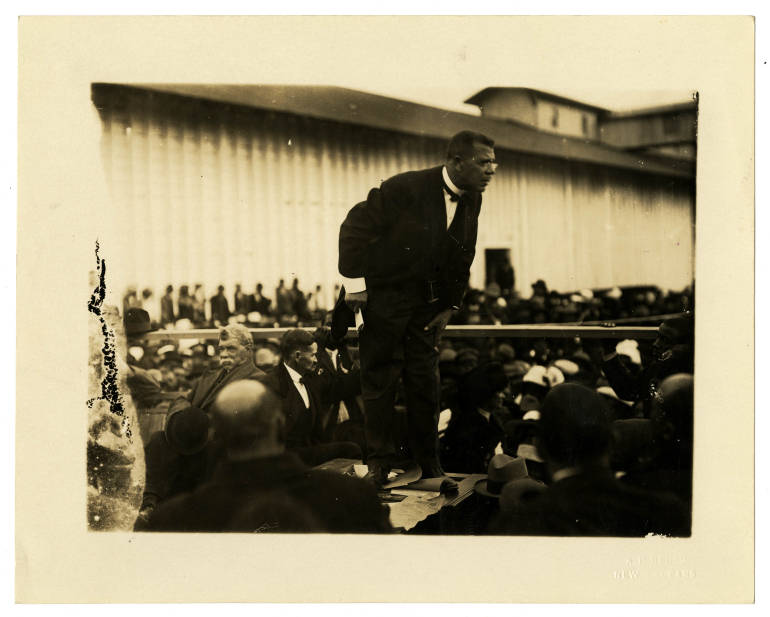

My favorite historic New Orleans photographer is A.P. Bedou, who has a striking photograph of George Washington Carver as a mature individual rather than the usual photos we see of an elder in a laboratory. Bedou was the official photographer for a handful of Booker T. Washington’s concluding years.

The SEEING BLACK project will cover photography in the United States from the beginning. There will be a book featuring photographs, a website, at least two major exhibits, and possibly a touring exhibition. The vision was ambitious but it was do-able.

I had an incentive to get out of the hospital.

While in the hospital, Tammy and a number of nurses offered great treatment–often saying “thank you for your service”.

My job in the army had been electronic maintenance of the Nike-Hercules Nuclear Missile, which included arming the warhead. Additionally, I had been trained in “chemical, biological and radiological” warfare. When my three-year stint was up, I made no secret about my intentions to leave.

By my third year I was an E-5, a basic sergeant level. I no longer had to make roll calls in the morning or the afternoon, although I did have to pull night-officer duty in the barracks every three weeks or so. But being in the army was no longer a burden. I even had my own room.

An army official promised me a “sweet deal”. If I would re-up, I would be given a $10,000 signing bonus and get promoted to E-6, a staff sergeant–I really wouldn’t have much I was required to do outside of my training duties in the states and missile maintenance on overseas assignments. Moreover, I would have a choice of Germany or South Korea for an annual overseas assignment. The truism was that the Black soldiers preferred South Korea and the White soldiers leaned toward Germany. But not for me. I wanted out.

I asked the official offering the deal, had he ever heard of Bobby Blue Bland.

He said no.

I explained that Bobby was a blues singer and had a song that explained my position. “If you don’t believe that I’m leaving / count the days that I’m gone”.

# # #

And now a word about money. If I were not a veteran being treated at the VA Hospital, there is no way I could have afforded the treatment I was receiving.

As my brother, Dr. Keith C. Ferdinand, asserted on one of his visits to see me, the high cost of health care was a major reason for bankruptcy in the United States. Thousands of dollars of doctor bills can wipe you out and tens–even hundreds–of thousands in hospital bills will drown the average family. Hell, even most upper class families could not absorb extensive medial costs.

Does it really have to be so expensive for this nation to offer quality health care? Moreover, it’s not just the cost of treatment that is too expensive, but the whole system that is structured against the poor and those citizens who most need health care.

Consider the cost of medical school. What it takes to matriculate through the established training and educational routines can set one back a small fortune.

One of the poorest countries in the Western Hemisphere offers top notch training for medical personnel including medical school to become a doctor. Cuba is exemplary as a source of medical training and treatment. Although far from a paragon of political freedom, Cuba offers free and/or inexpensive medical education to “minority” and other under-served students from the USA.

Health care in the USA is among the best and simultaneously among the most expensive. Those who can afford to do so, often travel to Mexico or Canada for treatment where prices are not so exorbitant. For example something as simple as eye exams and glasses are cheaper, not to mention the cost of non-difficult and/or elective surgeries.

I have no personal complaints about the treatment I’m receiving at VA. I just wish this level of care was available to all citizens.

Although I am thankful for my treatment, I can hardly wait to be discharged. I joke with some of the nursing staff that I’m going to do a late night get-away. One told me that I would be seen before I could get out the door. “Nah. I’m going one o’clock in the morning. I’ve already told my accompanist to have the car ready.”

# # #

Today it’s Easter Sunday. I wake up at 5:30 in the morning and hobble to the bathroom, only six feet or so from the bed. When I get back, I sit on the side of the bed, leaning forward slightly to ease the pressure on my backside. Pain in my buttocks when I sit upright is the most immediate result of the incident that propelled me to my long-term residence at CLC.

Even though it’s a little over a month that I have been hospitalized, there is no ignoring my health condition, especially the blood clots in my legs and the cancerous mass that is on one of my kidneys. I know the long term holds a serious operation that will include a major recovery period, but the reality is, I end up focusing more on day-to-day issues.

The mostly, but not exclusively, Black and female nursing staff is both attentive and competent in ministering to my physical wounds. On more than one occasion we talk politics and/or racial issues.

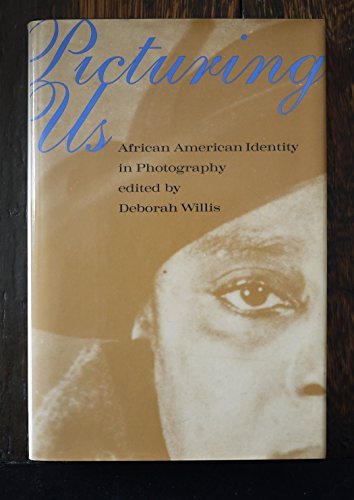

Late one night, or maybe it was shortly after midnight, when I shared the SEEING BLACK project with nurse Omika Williams, we get into a short exchange. I show her Reflections In Black, a collection of photograps detailing the Black experience edited by Deborah Willis. Ms. Willis is the preeminent expert of Black photographers and images.

Omika says she has an interest in photographs and a book on Blacks and photography. She says she will bring it the next time she comes to the hospital. A day later when I wake up, Picturing Us, a book that features writers discussing what specific photos mean to them, is sitting on my bedside tray. The book is edited by Deborah Willis. And yes, I have a copy in my library of books of or about photography, including more than a few featuring Black photographers.

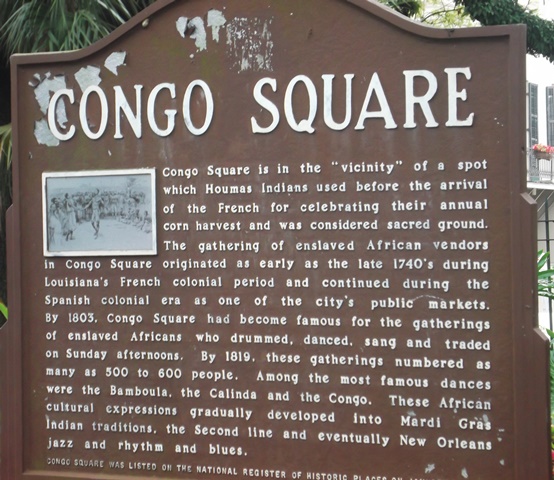

Omika also attends drum circles on Sundays in Congo Square. Those weekly gatherings, featuring dancers in addition to the drumming, is open to everyone–just bring your own drum or your happy feet.

Annually, Congo Square is also the beginning point for a ceremonial Maafa trek to the Mississippi River about a mile away. The Maafa demonstration specifically memorializes the middle passage, which included the torturous, trans-Atlantic trek that brought many of our ancestors to a city that at one point was the site of the largest slavery auction in the United States.

A few ask about my unusual name. Was I born that way? Why did your parents give you that name? Does your name have a meaning? I smile.

Black Americans have a way with names. Often our names have no specific meaning. They just sound African. My name, Kalamu ya Salaam (which means “pen of peace”), is Kiswahili, a Bantu-based language used throughout East and Central Africa. Born Vallery Ferdinand III, I legally changed my name in 1969/1970–first at Kwanzaa and then in the courts.

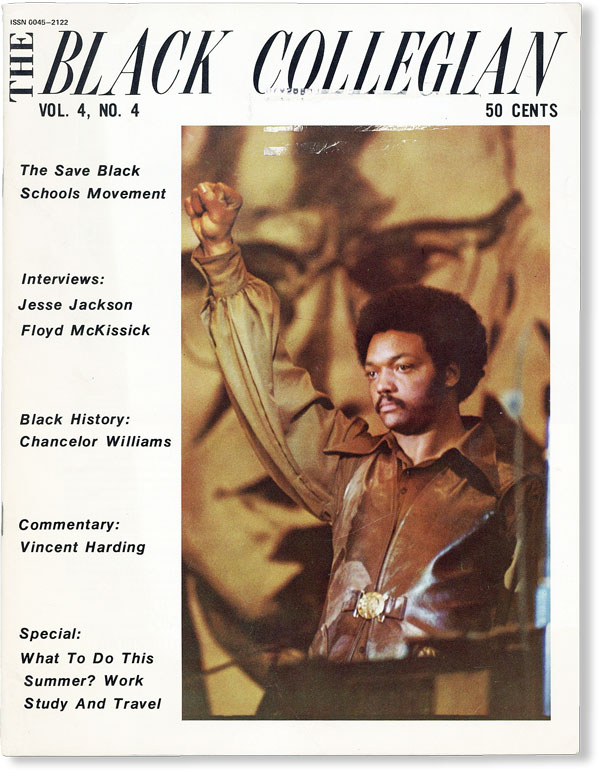

During my years as a founding editor of The Black Collegian Magazine (I served 1970 – 1983), I would sometimes take one of my five children with me as I moved around.

Once when visiting a layout artist who was doing work for us, I had my middle child, a daughter, with me and introduced her to Hal when I went to pickup some layouts. He stumbled trying to pronounce her name, “key…, ki…, caw…”. She quickly and self-assuredly asserted: “My name is Kiini Ibura Salaam. It means the inner-most part of something special, which is peace. What does your name mean?”

At that time, I had no way of knowing that Kiini would become an award winning writer and editor, with whom I joke: “I want to be just like you when I grown up.”

As we live our lives we often have no idea what the future will bring, whom we will meet on our life journey, and what influence we will have on others. I make it a point to relate to everyone. I know I got it from my father.

Our family was motoring to San Antonio, where my father was stationed in the army. I was very young, bundled into the backseat of our vehicle–a Buick, although it more probably was our first family car, which was a Kaiser.

It was very late at night. There was a White guy hitch-hiking along the way. My father stopped to offer him a ride. Big Val told my mother, Inola, to drive, gave the front passenger street to a man he didn’t know and squeezed beside his sons, while he sat directly behind the guy.

After I don’t remember how many miles, the guy said this is where he was going, and got out. Afterwards my father told us the reason he stopped, “It’s too late at night for anybody to be out there on their own. Besides, I sat behind him in case he tried anything.”

# # #

My wound care is the biggest immediate issue I “face” (which is a “joke” because the wound is on my backside!). During the fourth week of my stay, a duo of nurses led by Charlotte Jones and Gingerla Sanders usually administer treatment after I have taken a shower and donned a pajama top. I lay on my side and eventually rolled over to expose my backside.

They work quickly and we share moments of mirth. They are hard core New Orleans Pelican basketball fans, and are ecstatic when the 21/22 playoff series is tied 2-2. “Nobody expected us to be there. But we fight.” And a team who was not even supposed to be in the playoffs are giving the number one team in the league a hard time.

An onlooker might think it was crazy but as I am being treated for a serious wound, I and the nurses are laughing about how the Pelicans are showing out. As they are about to leave, Gingerla asks me where I am from. “Lower Nine.” And it’s on. Uptown. Westbank.

Like we say CTC (cross the canal): “I might take a killing, but I ain’t taking no ass whippings today.” Although I let them know I am an avowed Golden State fan, we all agree, we will be watching the Pelicans and their amazing run.

As for my medical care, I don’t even know the list of medications that an alternate nurse, Andreleta, later applies to my backside. These nurses do an expert and efficient job at wound care treatment. Until you have serious wounds on your butt, you have no idea of how discomforting such wounds are.

When I was in junior high school, I fractured my left leg playing sandlot tackle football. I ended up briefly hospitalized and shortly had a walking cast put on my leg, which allowed me to limp around as I attended classes. But that was minor compared to the inconvenience of the wound I now have.

We generally are unaware of how much we use our butt muscles to sit and to walk. As I recuperated, I would always have to steel myself to push off the bed and walk to the bathroom, or even to simply standup for a short stint. I still keep the cane nearby to aid my perambulations up and down the hallway.

Fortunately, nurses such as Tammy and Kia are truly concerned about my wellbeing. Invariably they ask if I need anything? Invariably, I respond: “to get out”, whether by formal discharge, or, if necessary, by simply walking away. Of course, “walking away” is no simple matter at this time.

Tammy is particularly caring. As the old folks say, she “goes the extra mile” to make sure that I’m comfortable and always checks to see if there is anything I need. Most of us, even those of us who are patients in the hospital, don’t realize how stressful and too often relentless are the plethora of duties a good nurse performs on our behalf.

Tammy offers to assist me in going outside, which means walking out on the patio located near my room, which is at the end of the hall. Although I’m grateful for small favors, I joke that what I really want is to go away much further than down the hall and outside on the upstairs patio. I don’t take for granted that Tammy treats me like a relative, maybe even like a cousin or brother. I, in turn, ask about her life outside of the hospital.

Most of the nurses are mothers, and not a few of them are single heads of households. It’s not easy to daily care for the health and well-being of others and at the same time maintain your private well-being, especially when you work a stressful job requiring both vigilance and mental acuity in providing treatment.

For health care workers there are very few moments when they can relax once their shift starts. Nevertheless, some of them like Tammy not only hold it all together, they do so cheerfully. Just the way they take your blood pressure or smile with you when they linger a minute to listen to you complain about the food or thank them for finding an extra blanket for you–I find the air conditioning a bit too chilly for my tastes, it’s all comforting.

Sometimes I get into serious conversations with nurses such as an exchange I had with Kia, who seriously embodies her Christian beliefs not just in her daily behavior, she also is serious about understanding her Christian philosophy.

Once after giving me my meds, Kia and I exchange views on the meaning of Adam and Eve being ashamed of being “naked”. I argue that there need not be any shame about being naked. I point out that pictures of indigenous people who live in tropical environments are mostly what we would describe as naked or near naked without any negative concerns about being nude. Kia responds that it’s more about being expelled from the Garden of Eden than their nudity.

I believe it’s a Christian conceit to view nakedness as a “sin” or, at least, something to be ashamed of. Part of my thinking about nakedness is a result of my wounds on my rear, which are usually treated and dressed by female nurses. I have no embarrassment concerning being naked in order to be treated.

Most of us don’t realize how many of our beliefs are grounded in Christian views abetted by capitalist views that ostensibly are in direct contrast to the viewpoint that money is the root of all evil. To me, one of the most controversial stories in the Bible is when Jesus picked up a whip and drove the money-changers out of the temple.

My interpretation is that the story validates both using violence and being anti-capitalist. Of course there are other interpretations but Jesus wielding a whip is a most un-Christ-like look.

But beyond all of that, my real issue is the misogynist undercurrent that is philosophically endemic to western culture. Two books that identify how the hatred of women is pervasive are The Alphabet Versus The Goddess: The Conflict Between Word and Image by Leonard Shlain and The African Origin of Civilization by Cheikh Anta Diop. Both interrogate patriarchy versus matriarchy, which is the philosophical conflict fueling what is sometimes characterized as the battle between genders. Actually the real struggle is around the ideological need to dominate women exhibited by many, if not most, men.

Dealing with the contradictions inherent in male domination of women is complicated within the Black community, wherein there is a widely perceived need to support Black men, who are routinely oppressed by diverse elements of the national environment on both individual and institutional levels.

Moreover, in our struggles to support Black men, we too often overlook our own sexism, and worse yet, we unthinkingly embrace the oppression of women. Once, before I arrived in CLC, when Tiaji visited me, my room was filled with a quartet of “my boys”, when a trio of doctors arrived making routine rounds, among the doctors was a Black woman of Nigerian descent.

Per usual, I was making light of a serious situation, striving to keep my spirits up. After the doctors and the visitors left, Tiaji lit into me, saying that I had been disrespectful of the doctor by joking about Nigeria. I was referring to the time on a brief stop-over, Tiaji had a major dust-up with Nigerian officers at the airport. A friend who came to see her was assaulted when the airport guards took her passport, went outside, and asked if anyone was there to meet this person.

Her friend identified himself and he was beaten and sent away. The authorities didn’t tell her what happened. Tiaji didn’t find out until after she left. I had warned Tiaji to be careful traveling through Nigeria. Many years later I joked about Nigerian attitudes when I lay in a hospital bed.

Subsequently, after everyone else departed, Tiaji didn’t hesitate to point out that she was shocked that I didn’t recognize how my unthinking joking was far from harmless. When Tiaji criticized me, I realized she was right and made a mental note to myself to be more careful. Regardless of my intentions, I indeed had inadvertently demonstrated how deeply sexism can worm inside any of us.

After listening to Tiaji, I also wanted to apologize face to face, however I never saw that physician again. In our organization, Ahidiana, we used to say: “if we are wrong, reality will correct us; if we are serious, we will correct ourselves.” That truism applies to all of us, especially those of us who strive to live a principled life.

Black folk are generally oppressed by patriarchy but our public leaders, who are overwhelmingly, mostly male, often in subtle and inadvertent ways, fail to recognize and confront sexism. This is especially true in the areas of entertainment and athletics. However, it is also counterintuitive true that, despite rampant sexism, without our private and public spheres of activity, Black women share or shoulder the major burdens of leadership, from home to workplace, and beyond.

It is accurate to assess that society at large restricts Black men, not allowing us to be the equal of White men, however, we make a major mistake when we equate patriarchy with manhood, as if being a man inescapably means embracing patriarchy. On the other hand and by contrast, matriarchy is not based on elevating women by down-pressing men.

I believe we have contradictory and often conflicting forces at work in our community. So many of our households are female headed, plus a very high divorce rate leads to single women alone (and lonely) too often bearing the burden of raising children, whom generally remain with their mothers. Thus, while we continued to be surrounded by images in the mainstream of the typical family as husband, wife and children, the reality among our people is far from what we are shown to be a desirable norm.

We are routinely taught to aspire to the norm of the establishment defined nuclear family. But that is not how we live, how our social conditions exist and, to a large degree, how establishment mores influence, if not outright define and determine our behavior.

Thus, there is a serious issue of cognitive dissonance. We believe one way and live another. In a number of cases this dissonance leads to self-loathing, or at least a belief that something is wrong with us and that we should be more like what we are taught is desirable. While that dissonance is particularly hard for Black women to deal with, the situation also affects males, too many of whom, over-compensate and insist on being either a society defined typical head of household, or a totally independent man who wants to be in charge of everything and everyone encountered.

In the USA today, a real question is how to be a man without being an overbearing patriarch. There is no easy solution. Without directly thinking about the question, most of us men do as we have been directly taught and indirectly acculturated. We strive to be what our families, our communities, and the overall commercially-oriented culture teach us to do: we think (and act on those thoughts) that being a man means being in charge.

Inevitably, being in charge includes being in charge of women–if not directly controlling women, at the very least garnering their admiration, which we also take to mean the submission of women.

# # #

The imposed hegemony of intellectual knowledge over manual labor is reflected in the social structure of most hospitals. I have identified four levels of labor in the typical hospital.

It is easy to look at these four levels and to resultantly, place one above the other on a totem pole of authority and relevance. However, the deeper truth is that we are all humans defined by how we work, or don’t work, with each other. Thus, I believe labor relations are generally more important than a number of other social factors.

Indeed, within factors such as gender relations, or interaction between people of different ages, differing religious and/or political beliefs and affiliations, work realities likely dominate, if not outright determine, social relationships.

Acquiring, having, using and enjoying things might be nice but ultimately “things” are not fulfilling. Regardless of what we are shown in the media, the acquisition and utilization of things are not the deepest definition of the good life.

The conflict between acquiring things and living the good life is a social contradiction that we all grapple with. There is the need to make enough money to meet the cost of living in the here and now. In this society, the good life is not free, indeed, the good life is expensive. Too often the cost is not simply a matter of money.

A cynical argument goes: money can’t buy you love, but money will buy a measure of satisfaction while you look for love. Thus, we work for a paycheck regardless of job satisfaction, if there is any. Of course, another old adage is also true: the more you have, the more you have to take care of. To use the vernacular, maintaining the good life is a bitch.

Laying up in a hospital bed, offers hours and hours of time to think about one’s life. Such self examination includes analyzing one’s immediate condition and environment.

One of my thoughts is about what I call the four levels of hospital work. I used to identify the levels starting with level one as the foundation. However, invariably the bottom is considered, well, the bottom, the least important, rather than the foundation, upon which the whole structure relies. Without the bottom the top can not truly function.

Rather than using a totem pole as the model, let’s consider a wheel, or a pie-chart, to describe the hospital. No part is non-essential, even though some parts may be more intellectual or more medically critical than others.

One major slice is maintenance and housekeeping. Those who are responsible for upkeep and cleanliness are absolutely necessary for the running of a hospital. In large part they keep the lights on, the machines running, and the rooms clean. Try maintaining a major hospital without their services–and they are overwhelmingly Black laborers and generally female.

Another slice is the nursing corp, which ranges from aides to highly trained RNs (i.e. registered nurses who have studied medicine). They daily, and hour-by-hour interact with patients who require treatment and therapy to get well. Nurses are the main points of interaction with patients.

Here I will point to an aspect that is too often overlooked. Nurses provide human contact through language and touch. Their interactions, whether linguistic or tactile, are essential to healing.

In our normal day to day relations, we have thousands of exchanges. Verbally we banter, we make requests, we state our intentions, our feelings. It makes a big difference whether there is someone to whom we can relate, someone who responds to us, and with whom we feel connected–after all, there is nothing like two people being momentarily connected in oneness. Even when it is one helping the other, it’s a great feeling. Both helping and being helped feels good.

Personal contact and caring is a fundamental element of recovery that is too often overlooked or minimized, but it is axiomatic: recovery is both physical and social. Our feelings are both physical and emotional. We always feel better when we function together with each other.

The third slice is therapy and specialists, who range from x-ray and laboratory technicians, to physical and occupational therapists, plus a whole cadre of other specialists, such as pharmacists and social workers, who deal with diverse and too often unseen or even overlooked aspects of medical diagnosis, treatment, and therapy.

For example, I had no knowledge of occupational therapy, but it is essential for me because I live alone. Before I am released, the staff wants to make sure I am ready to resume caring for myself.

The fourth slice is, of course, the physicians and the medical knowledge they bring, which is extensive. However, in my case, no one has yet solved the mystery of what happened to cause my temporary immobility.

My brother, Dr. Ferdinand, recalled a specific ailment that beset my uncle Lloyd Ferdinand in Chicago. In his latter years, Uncle Lloyd couldn’t move his legs. Keith said he probably had dermatomyositis, an uncommon inflammatory disease marked by muscle weakness and a distinctive skin rash.

They tested me but thankfully the tests were negative. Besides, on the third day, I was up and walking, although haltingly. Nevertheless, I was moving on my own. My legs were working. Whatever caused my weakness remained undiagnosed.

No matter the medical mystery, I was ready to go home. At the same time I realized another week of wound care would make a significant difference. More than getting discharged, my gold standard was simple: once I was released, I didn’t want to have to return. At least not until the kidney operation, which was going to be a whole other issue to deal with.

# # #

I have been a traveler on a long and winding path. Actually, more like a pilgrim seeking solace as I forge my way across mountains and rivers, wander the countryside and survive, and sometimes even thrive, in the metropoli known as New Orleans and other cities. I’ve yet to find a safe resting place. Along the way I’ve learned a lot and even taught a little, as I’ve tried my best to pass on the nuggets of wisdom I have mined from my travails.

But I don’t feel sorry for myself, and no ways tired. I wanted to be a writer without realizing that, ok, if that’s what you want, life will give you something to write about.

I remember being a founding editor of The Black Collegian Magazine–a thirteen year journey during which I thought of myself not merely as an editor but rather as a cheerleader for others. I considered many activists and writers more important than myself. They were proponents of ideas and issues far larger than me.

I followed a path of turning ideas into reality with no concern for fame or fortune. I guess you could call me a true believer in the power of the word, both written and spoken. Indeed, my forte was doing interviews with all kinds of folk, especially artists, activists, and musicians, telling tales of their own loves and struggles. That’s life, or at least that was my life, my choice, what I felt I was born to do.

Despite the debates, fissures, and even a shoot-out, that characterized the Black nationalists versus Marxists separations that tore asunder attempts to unify anti-establishment elements, small groupings of us tried to hold on while the majority of our people voted with their feet for integration into the larger American society. The 2009 election of Barack Obama to the presidency solidified a resurgence of belief in the American way among people of color.

On the other hand, Obama was followed by a one-term ascendency of Donald Trump to the presidency. Not since the Civil War has the country been as polarized as is post-Trump America. Whatever one’s political persuasion, there is a general dismay about the social status of conflicting elements of America, whether those elements are Democrat or Republican, advocate or opponent of abortion, or a myriad of other political or social issues. It is hard to be cheerful and optimistic about the immediate future nationally, as well as abroad, in the face of disease (particularly Covid) and war (particularly in Ukraine).

But as terrible as they are, the national and international issues also play out internally. You wake up, look in the morning mirror, and suddenly recognize, the battle is closer than you ever thought–the hardest battles are actually against our own weaknesses and inabilities to change the situations overwhelming us.

Be strong, brother. Fighting others is easy, battling with yourself, ah, that is the most difficult of all the wars you will ever wage.

The battle to better one’s self is especially difficult when we are simultaneously trying to resolve the conflicts and contradictions within one’s life, particularly if we are a male. The vicissitudes of being a man in modern America is complicated not only by the realities of race and the uneven pressures of economics, this effort to identify manhood and to define how one ought to live as a man is a complex undertaking.

I taught high school juniors and seniors in our Students At The Center (SAC) program. I was a co-teacher, with Jim Randels, in AP (advanced placement) English 4 class, as well as an instructor in a creative writing class. We published pamphlets and books. Our most popular title was Men We Love, Men We Hate, a student exploration of relationships with fathers, brothers, sons, cousins, friends, acquaintances, and, too often, with males, who were reductively, enemies.

That book was our most popular publication, so popular that students from other classes would request copies, and occasionally even fleece a copy for their own personal use. Abbie Hoffman had nothing on this often surreptitiously acquired book.

I viewed the disappearances as an indication of young people actually seeking to mature as they dealt with the conflicts and conundrums of achieving adulthood. Not only did the stories help the authors become critical thinkers, the writing also helped their peers. No teacher could ask for more from their students than to become critical agents of their own growth and development.

What is life? An eternal struggle to make the self better, regardless of the environmental forces working sometimes to help, but too often working to hinder, one’s development. The saints are the ones who smile instead of scowl as they push on through both sunshine and storms.

You want to be a writer, huh? Well life will give you a lot to write about.

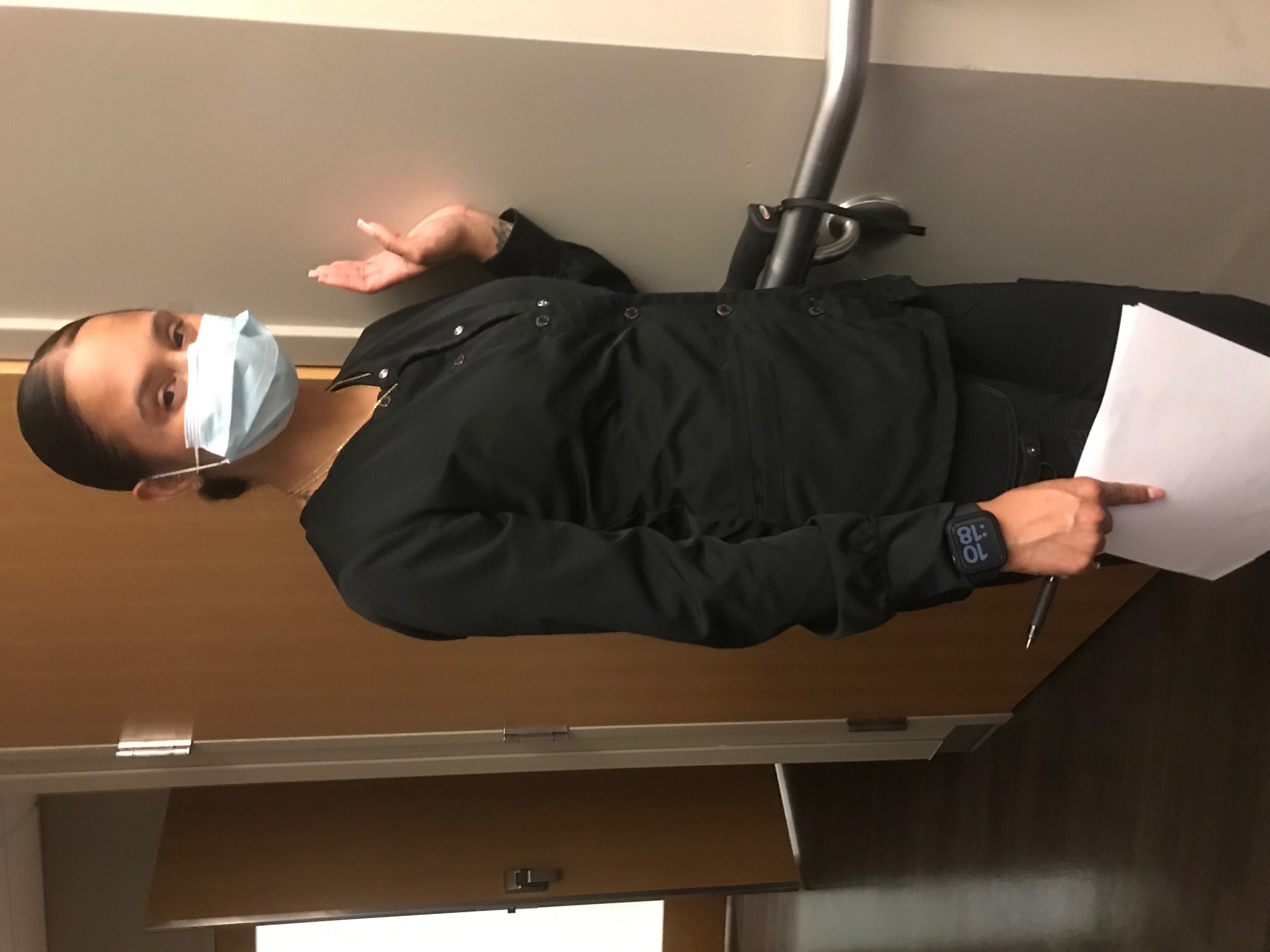

Certified nursing assistant, Kaiana Santiago is emblematic of a section of New Orleans, the seventh ward, known for its light-skinned, proud creoles of color. Many never denied being Black, just a lighter shade of darkness.

As she cares for me, I learn a bit about Kaiana’s background. “Your people from Cuba?” I ask because of her last name. “No. My grandfather is Puerto Rican.”

Which means to me, that they don’t take no shit. Don’t get it twisted. They may not look dangerous, but these are the people who literally shot up Congress in a 1954 armed attack (look it up if you find that unbelievable). Over the years, they even took over a hospital. The Young Lords put a Latin Boogaloo twist on the Black Power struggle–and if you don’t know, you better ask somebody.

We African Americans are not the only ones who have a long history of struggle. Indeed, many Puerto Ricans identify their struggle as simply the Spanish-speaking and/or bilingual part of our larger struggle for self-determination, self-defense, and self-respect.

“Pa’lente!” Go for it! Or as JB might have sang, “go head on with your bad self”.

Another disturbing aspect is the near universal, establishment engendered identification of Black women with a sexuality that is either wanton or taboo, a forbidden fruit to be savored but also exploited. This is especially relevant for the light-skinned Black woman, subject not only to exploitation inside the race but also the subject of a pernicious activity among our people known as “passing”, which refers to light-skinned Blacks living as though they are Whites.

Passing was twice mythicized, first in an important novel by Nella Larsen and second, almost a century later, in an insightful cinema expose. Ms. Larsen published two iconic novels at the end of the “Jazz Age”, i.e. the “Roaring Twenties”. Her books were Quicksand (1928) and Passing (1929), the second one of which became a searing Hollywood movie that shocked some and was a total revelation to others. Passing was actually no bed of roses, in fact it was a crown of thorns that punctured the so-called valorization of Whiteness as the point of living as though one was actually the “other”.

Although passing was more common than generally acknowledged, a quintessential example of passing was by acclaimed literary critic Anatole Broyard, whose previously hidden, or perhaps simply ignored, African heritage was totally obliterated when Broyard intentionally passed.

Broyard’s Blackness was publicly, and near scandalously revealed by his daughter Bliss in her book, One Drop: My Father’s Hidden Life–A Story Of Race And Family Secrets. When she was an adult, Bliss was told of her father’s heritage just before he died. She would go on to reveal the story in her writings and identified herself as a person of mixed race.

As an interesting side note, one of my classmates in high school was a Broyard, although he didn’t look White. Broyard was New Orleans born and some of our classmates would playfully pass for White when school was let out and then regale us with tales of their crossing the color line in school the next day.

In America, racial identity can be straight-forward or can be obscured, partially dependent, of course, on how one looked. The upshot is that there is both an individual and institutional complexity to racial identity that is seldom without some degree of either angst or pride, distancing or embracing. Being of part Black heritage is one thing, but looking Black is a mule of a different horse.

An educational work that we in SAC felt was of insightful value was The Pedagogy Of The Oppressed by Brazilian educator and liberator, Paulo Freire. His book, in detail, not only argued that many of us are oppressed but also, and more importantly, demonstrated how we often internalize our own oppression.

As Carter G. Woodson presented the case in his important work, The Miseducation Of The Negro, not only will we seek the back door designated for our debased place in society, if there is no back door, we will often create one rather than assert our right and responsibility to be fully human and, as they say in church, to act accordingly.

The detriments heaped on Black people were not unique to Blackness, even though it was true that we suffered a crippling racism, which was a twin evil often co-joined at the hip with economic exploitation. Social segregation affected a far wider sector of the national population than being Black alone. Moreover, exploitation, sexual as well as economic, was and remains the American cross that women were forced to bear.

In the twentieth century the last two major movements against racism and economic exploitation were the Civil Right/Black Power struggles of the sixties and seventies, and the Women’s Liberation Movement of the seventies and eighties.

Needless to say, many of the effects of yester-year are still in effect today. “A luta continua” (the struggle continues) is real. Bringing these issues to full fruition has proved to be far more complex than originally envisioned.

# # #

I’m from a much maligned area of New Orleans, the Lower Ninth Ward. Located on the southeast end of the city, between the Industrial Canal and St. Bernard parish, and bordered by the Mississippi River on one side and the marshlands off of Florida Walk on the opposite. Our little redoubt was virtually a self-contained community of people newly arrived to the city who all looked out for each other.

The river side of our stomping grounds was mixed and was predominately White, but once you crossed St. Claude Avenue, the complexion was overwhelmingly Black, although in the fifties and very early sixties, Tennessee Street, for some reason, as I remember it, was mainly White. Tennessee ran from the bridge out to a canal just yards from the levee by the swamps. However, after the Korean conflict when soldiers, such as my father, returned home, even that street transformed to being mainly Black populated.

There used to be only two bridges into Lower Nine. One was on St. Claude Avenue. That was the main bridge and led into St. Bernard parish, which was formerly, the stronghold of segregationist political leader, Leander Perez. Through hard experience we had sense enough not to be caught down there overnight.

I faintly remember my father and some of his post-war friends vainly trying to establish a Black Country club in what we familiarly, simply called “the parish”. Although they worked mightily and invested many man hours and hard-won money, they were forced to surrender to the blatant racism that was in full flower and nowhere near abating, as it later did in the new millennium.

The other bridge was at Florida Walk. We used to euphemistically call it the “back way”. That bridge was always up and also had a railroad track attached, which ran down into St. Bernard parish.

In the fifties, when I grew up below the canal, I didn’t realize the historical significance at the time, but I was able to see the last of the fabled baseball Negro League games in a field a few blocks from where we lived.

The ninth ward was so isolated from the main part of New Orleans that for the longest period, there was only one bus line on St. Claude that ran down there, from Canal Street to the Domino’s sugar refinery in St. Bernard parish, a few blocks below the city limit. Indeed, when the city finally constructed the Judge William Seabrook Bridge, which we simply called the Claiborne Avenue bridge, that was such a major event in the Lower Nine that my father packed us into the car and we were among the first to cross the waterway when then Mayor Victor Schiro officially opened the bridge.

We lived back-a-town, way down and almost on the edge of the city on St. Maurice and Law streets. There were only two streets after us, Tricou and Delery, before you were out of the city. And heading east there was only a canal, railroad tracks and a levee that separated us from the marshlands, which were our early playground, full of snakes (especially cottonmouth rattlesnakes), muskrats, rabbits, raccoons, diverse birds, cypress trees and flora, fauna, and all types of general Louisiana wildlife, including alligators and gar fish with their huge teeth.

Typical of youth, we picked wild blackberries, caught crayfish in the canals, and took our growing up environment for granted, although we were aware it was different from most of the city. Also, typical of youth, we loved where we were from and thus it was no surprise to me, over sixty and seventy years later, when I find out that Christina, one of my nurses, is from lower nine that we strike up an immediate camaraderie.

I don’t mean to demean or detract from the care that other medical staff give, such as Tiffany and Gerald (one of the few male nurses I encounter–he goes by the moniker “Zee”), as well as not from any of the other personnel, who are first rate. Nevertheless, those of us from the the mighty nine have an extra bond that we recognize and revel in, almost like we were war time vets greeting each other.

Christina Dunbar tells me to hold on, she will be back when she gets off. On the return visit, Christina offers me a cup of chilled, cold watermelon which she says she has brought from home to help her through a long, twelve hour shift. You can’t fully appreciate watermelon until you are laid up in a hospital bed and have the succulent juices flow down your throat as the cool cubes melt in your mouth. Watermelon. Asante sana (thank you very much) Christina.

The next day I am effusive in thanking her after she asks was it ok? I smile more than I have since being here. Christina says it’s no big thing. I smile some more and we proceed to talk about the bridge, the turnaround on Caffin Avenue by the funeral home, and a number of other L9 landmarks.

As we continue to talk, it is also Christina’s turn to bandage my wound. As Christina medically ministers to me, we continue to talk about the little things that are common to people from L9. Even though we are more than a full generation apart–I’m 75 and Christina is in her thirties–our home turf is a shared experience.

# # #

Aron Chang has come to visit with me twice since being at CLC. We talk about the struggle in general and particularly about anti-Asian aspects of life in the USA and elsewhere. Since I was stationed in South Korea; did an 18-day tour of the People’s Republic of China–I happen to be in what was then Peking, when Deng Xiaoping was rehabilitated and brought back to power (there was a celebration by literally millions of people in the streets, I had never witnessed anything like that before or since); and one-day or overnight visits to Tokyo and other cities in Japan, I had developed an openness to Asian views and values from the Far East Orient.

One lasting habit that has stuck with me is removing one’s shoes when you enter a home or apartment. People usually move around inside in slippers or socks. When I was in Korea that required the extra effort of unlacing combat boots. Over fifty years later, I generally still follow the practice of leaving my footwear near the front door.

Aron and I were more interested in what it took to make major changes to benefit the masses of people rather than for the benefit of authority figures. We talk about the iconic revolutionary figure of the 20th century, Che Guvera. I ask Aron if he had ever read Che’s Congo Diary. Aron says no. I have a copy sent to him and the second time Aron visits he and I briefly converse about that important document that never attempted to hide or excuse the many problems that Che encountered, including Che’s own misunderstandings.

We also discuss the anti-Asian biases that run throughout modern American history–modern meaning post Civil War, including the Chinese exclusion legislation and the Japanese-American interment camps that were built and utilized during World War 2 after the bombing of Pearl Harbor. Although I don’t recall his name, I remember a fellow soldier whom I was close friends with during the nine month period with whom I was in training for electronic missile maintenance. He was born in an interment camp and was subsequently then serving in the army with me.

My interest in international issues works in confluence with my interest in foreign cinema. I’m a cinephile who was baptized in film during my brief stay at Carleton College where I was introduced to films such as Knife In The Water (1962), an early movie by Roman Polanski and Kanal (1957) by Andrzej Wajda, whom I consider one of my all time favorite movie makers. I was particularly stuck by his examination of the French Revolution in his major film Danton (1983), which ended on a modernist moment when the hero ascends steps into modern society. But there were so many other Wadja movies that I deeply admired.

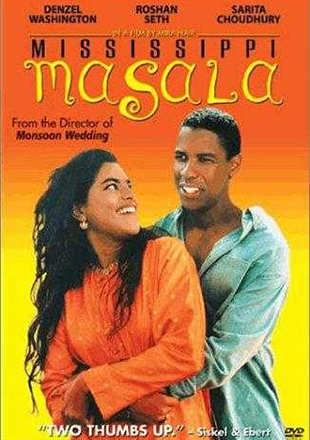

Which brings me to movie makers internationally, especially Asia directors. Mira Nair is particularly important in both her willingness and ability to illustrate cultural clashes and connections between people of color and their families within the racist environment of Mississippi. Her film, Mississippi Masala (1991), which features Denzel Washington and Sarita Choudhury, is especially noteworthy. Denzel’s character falls in love with a young woman of Indian heritage.

I was fascinated when I encountered an interview with Ms. Nair that discussed the making of the movie, as well as the arc of her career as a filmmaker who deals with the tensions and resolutions of cultural encounters beyond the stereotypical black/white and all-American/foreigner-immigrant situations.

# # #

I slept well and only woke up once overnight, however, after close to two months in the hospital, I am more than ready to leave this facility, yet at the same time I realize that this journey is not even half-way past the whole of my illness. I’m not afraid, but I’m tired of this.

In a few months, before me looms an operation to remove a presumed cancerous mass on my kidney. The severity of the near future does not cause me pause. I face my night with both eyes wide open. Whatever I might bump into will not deter me. Regardless of the wounds on my body, in my head I am ready to carry on.

Confined to the CLC, I have watched and/or listened to a lot of cabe news. I can’t stomach the bulk of television programming. Indeed, I find much of it, including the so-called news, not just distasteful but outright repulsive. Why? Because in a number of examples, political policy (driven by economic motives and incentives) is at odds with the wellbeing of the majority of the population. This contradiction is particularly sharp in the United States with the recent revelation of the proposed reversal of Roe vs. Wade, which will directly lead to the prohibition of legal abortions.

Again, to quote Muddy Waters, “I’m a man”, but it is clear that the proposed Supreme Court ruling directly affects me. I do not believe that men have the right to legislate what women can and can not do with their bodies but that is not how Republican politicians in particular vote. The vast majority of those who vote “pro-life” are actually patriarchal and “anti-abortion”. Whether overtly through their actions or covertly because of assumptions and beliefs, most men (particularly politicians) assert that they have the right to limit, if not prohibit, women’s rights of self-determination.

Part of the anti-abortion position is based on a fear that in both population and politics, non-Whites will eventually dominate Whites in what some have dubbed “the replacement” theory, as if the United States was not stolen land based on the genocide of Native Americans and the racial exploitation of African Americans and, increasingly, of segments of the Latin American populations. pluralize Latin Americans because they represent widely varying cultures from Mexico, our next door neighbors, to Peru, the most far-flung of our associates south of the border.

Moreover, beyond the international demarcations, a number of male authority figures do nothing, or vote against, policies that provide direct aid and assistance to families in general and to women’s health policies and programs in particular on a national level within the United States. Now is the time for conscious men to stand up for women’s rights.

The issue is self-determination: do women have the right to determine their lives, to determine how they deal with pregnancy? Simply put, should men have a right to make rules governing how women control their own bodies? Full stop.

The argument is that a fetus has rights, that a fetus is an individual, or potential individual, with the full rights of an individual. In a similar way, those who advance the pro-life argument are often the same as those who argue that in legal jurisprudence a corporation is the same as an individual, even though by definition a corporation is composed of a group of individuals.

Legally, all the members of a corporations are not subject to the same legal overview as individuals are. In other words, the corporation can function in ways that an individual either can’t or where an individual is ineffectual. For example, even though most corporations are overwhelmingly male dominant, corporations legally do not have gender.

Except, once a woman becomes pregnant, state legislatures (i.e. mostly men) can make laws that restrict a woman’s ability to terminate a pregnancy. Question: should the rights of a fetus over-rule the rights of the pregnant mother?–especially since the fetus is not yet a self-contained individual, but instead is dependent for its existence on the female host.

Do the rights of a fetus to grow to full term over-ride the decision of the woman, the host, to end the pregnancy? Or, put another way, does the fetus have more rights than the female host?

There is no easy answer.

When we consider the gender context we understand that the so-called “pro-life” argument is most often an extension of the patriarchal power to determine the actions of women. If we believe in individual rights, and, in particular, a woman’s rights to choose, how can we elevate courts to the power to prohibit a woman’s rights to choose to terminate a pregnancy, especially when the fetus could not survive outside of the woman’s body?

Should men have the right to determine what a woman can or can not do with her body?

In the context of gender relations, men believe their social power trumps female self-determination. Wherever patriarchy is dominant, women resultantly have lesser power, whether we are talking about individual power over their own bodies, or when we consider women as a group having and using social and political power.

Regardless of how we frame the abortion question, the deeper question is will we or won’t we support women’s rights to control their own bodies, including the right to terminate a pregnancy.

# # #

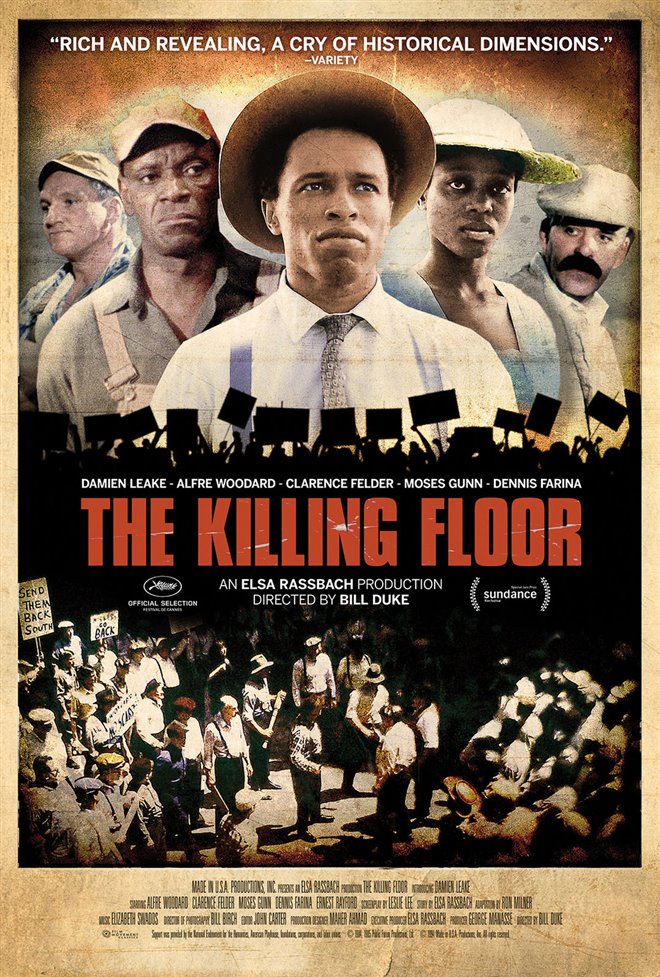

A movie called The Killing Floor (1984) is a pro-union look at the effort to organize workers, many of whom are Polish–hence the derisive term “Polack”–and others of Eastern European heritage. Set in the Chicago stockyards where cattle, primarily cows and pigs, are slaughtered. Without being overly graphic this movie makes clear how hard and psychologically taxing those killing floors were.

Here is a statement from the director, Bill Duke. Nothing was easy nor without contradiction and conflict. People, slaughterhouse workers in particular, were required to make great sacrifices for a chance at a better life. Although didactic by today’s standards, the movie highlights the pushes and pulls that impacted Black labor in a White controlled environment, especially during the war years when signing up to be a soldier and being paid to fight in the trenches was a viable alternative.

The Killing Floor is unstinting in illustrating the contending forces bearing down on each individual even if the individuallity of the participants are subsumed within the larger context of social conditions.

For example the language differences are highlighted, particularly as some of the union leaders speak Polish and other languages to workers who have become bilingual. This is a deep characteristic, especially because Black workers, ancestrally come from tongues that are unknown to them and were not only forced to abandoned their heritage languages and embrace English, but these workers are also subjected to linguistic amnesia.

Africa and African languages are so long ago, so far away, so forgotten and remembered only in either an idealized manner or, as is most likely the case, only in the demeaning terms presented as the American mainstream teaches us what Africa was and is.

In one sense our skin marks us as different, yet the real difference is in our culture, or should we say lack of a conscious culture other than imitating and/or appropriating the mainstream. There is nothing subtle about the movie, set during the World War years, yet we can miss the specifics of the realities that underline the obvious. The movie presents most Blacks as not only oblivious to our cultural essence and social conditions, but also unaware of how organizing can mitigate, if not totally overcome, our ethnic oppression and exploitation.

Black workers are introduced as both a divisive as well as a decisive element. Rather than sugar-coat the inevitable conflicts, this movie uses the tensions of difference in what Obama would call a “teaching moment”.

There is no easy way to bridge the differences, we all have to struggle to cross over from where we are to where we want to be. Moreover, getting to our envisioned promised land requires us to trod new territory and to learn new ways of living, including embracing the other as another, although different, part of ourselves.

The struggle teaches us that we are all exploited, and to a lesser degree all oppressed even as there are differences in the severity and frequency of our oppression and exploitation.

Every step forward requires leaving something behind. The question is are we prepared to pay the cost of progress? It is never simple to give up what we know in order to achieve what we hope for, especially when we have not fully calculated what it takes to win, keep and enjoy our hopes and dreams.

This movie alludes to the fact that it is not only four-legged animals that are slaughtered and consumed. The question is will we stand up for ourselves, in league with others who are also taken advantaged of in a society within which the rich exploit labor and do all they can to discourage union organizing.

We are offered creature comforts–big screen televisions, fancy automobiles, access to education and material amenities–in exchange we are required to forget from whence we came, and to a lesser, but more likely greater degree, to separate ourselves from our less fortune brothers and sisters.

All the raw materials required to live a good life are found in Africa, particularly the minerals that are required to make our cell phones and computers work. Honoring origins is important unless we become unconscious accomplices in our own oppression and exploitation.