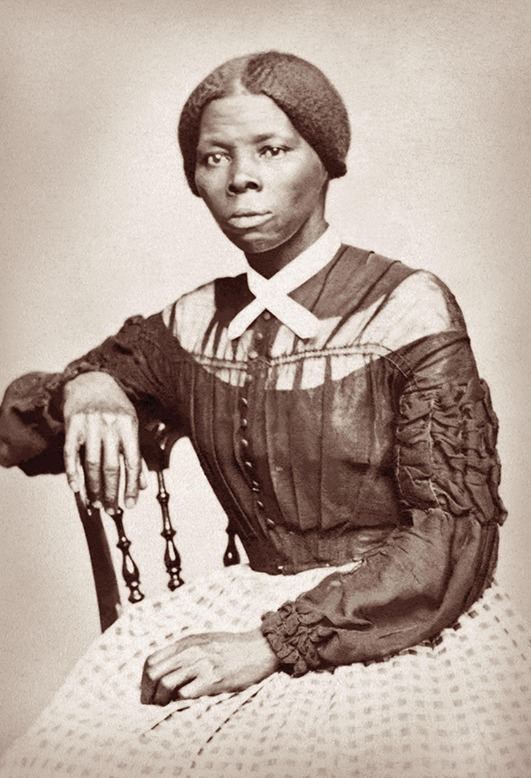

Harriet Tubman (born Araminta Ross, circa March 1822 — March 10 1913)

Because we live in a modern world where men overwhelmingly have wrested and near exclusively approbated the right to rule–we even believe that it’s odd, if not outright wrong, for women to be in charge of our society. We consider it an oddity when women act like men and take charge. Because of all of that and more of that madness, we too often end up with an adversarial attitude toward assertive women.

Men are born of women and although men can not conceive and birth people, we somehow come to the conclusion that men, and not women, should rule. Given the prevalence of this way of ordering society, many even think that only men should be in charge and support the exclusivity of men in leadership positions.

Fortunately, not all women think that way. Fortunately, there are women who step forward to challenge gender oppression and gender exclusivity. Moreover, women warriors, who are often also mothers, are not ipso facto opposed to men, nor to female leadership because of gender considerations and restrictions–revolutionary women do not hate anyone based on gender but rather are opposed to those who embrace sexist patriarchy (i.e. exclusive male rule) regardless of their gender.

Real revolutionaries believe and know that, regardless of gender, we all can be in charge and, if we are not careful, we all also can work against our interests and become ardent supporters of gender-based oppression.

Fortunately, our history is full of women, and a significant number of men, who believe that both women and men, based on their abilities, have a right to rule. Whether women actually lead societies is based on the conditions within a given society rather than the so-called “innate incompetence” of women.

Towards the goal of an egalitarian society we need, and should cherish, female liberators. Here is a small (although far from exhaustive or exclusive) library of books about Black women in America that every home should own and study. Moreover, scholars and activists are constantly creating and/or unearthing more instances of relevant documentation.

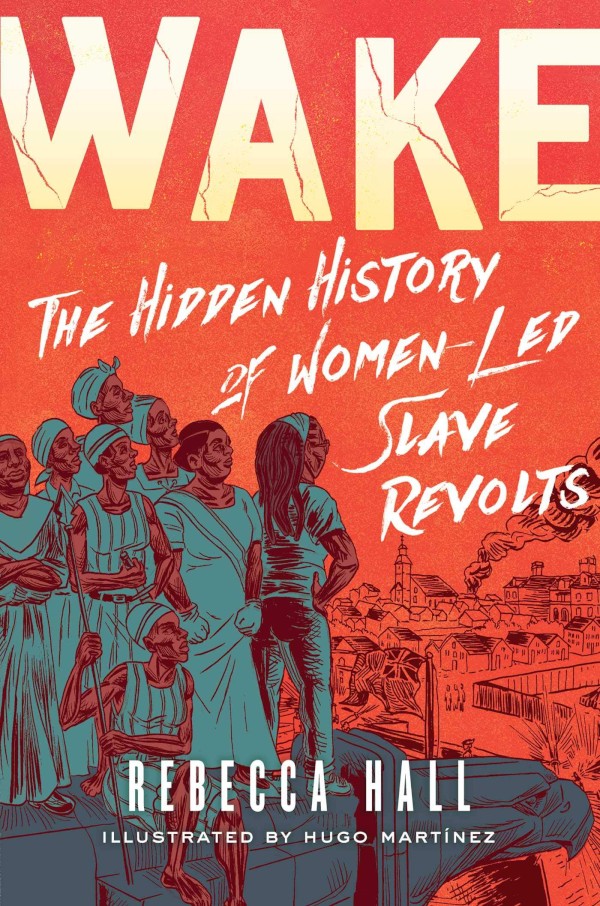

Early on, prior to the 1776 founding of this country (and even before in Africa and subsequently on slave ships) Black women were at the forefront of the freedom struggle. Read about this too often overlooked aspect of our history in this graphic-book written by Rebecca Hall and illustrated by Hugo Martinez.

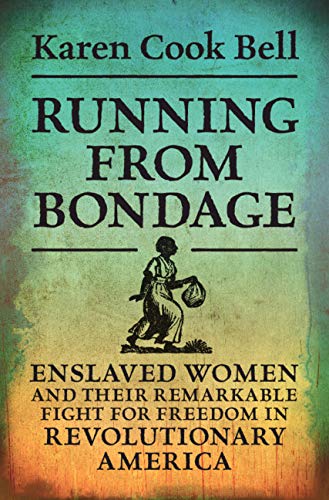

Through the investigation and use of advertisements for the effort to capture runaways, scholars have begun to document the numerous instances of who and how our people escaped slavery. One book that is important in our anti-slavery history is Running From Bondage that tells the thrilling stories of fugitive women–yes, the story of females who chose freedom or death over the life-long indignity of chattel slavery.

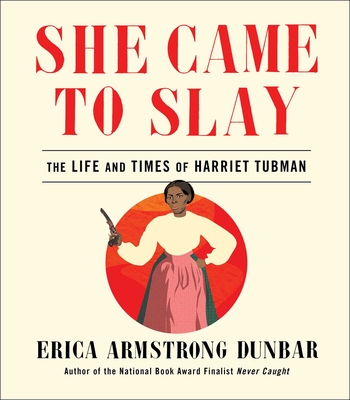

Of course Harriet Tubman is our best known and most celebrated American-born freedom fighter. She not only escaped slavery but returned south numerous times to lead others to escape. A simplified summary of her subversive activities is recorded in the book, She Came To Slay. Significantly, our “Moses” was the only woman to successfully conceive and execute a major victory against the Confederacy during the Civil War: The Combahee Ferry Raid that resulted in the freeing of around 700 enslaved men, women and children.

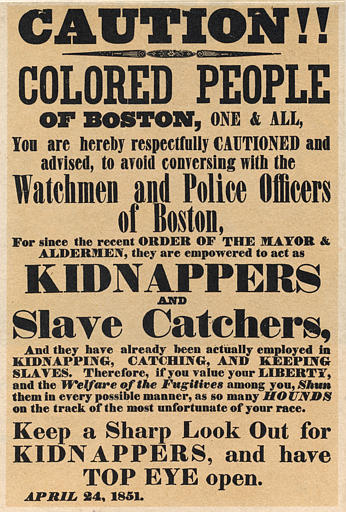

Most of us know that if we are caught up in the criminal (un)justice system we will need expert legal representation, however, although we feel it is true, not many of us recognize that for the majority of America’s existence, Black suffrage and freedom has been illegal. In fact the infamous 1850 Fugitive Slave Act declared not only were the fugitives subject to re-enslavement but any one, including state officials, who aided fugitives was subject to fines and/or short imprisonment.

The first, and less stringent, fugitive slave law was propagated in 1793 and declared that running away was against the law because the enslaved were the legal property of slave holders.

Significantly, the right to vote was, and remains, a major issue in our alleged democratic society. Although voting rights for Black people was a major issue before and after the Civil War, many of us are not aware that voting was gender specific prior to 1920. Just as the fifteen amendment to the vaunted constitution acknowledge and legalized the right for Black men to vote, that same act did not include women. Regardless of color, women were not awarded the right to vote until 1920.

During the Civil Era, one woman in particular argued that both Black men and Black women should enjoy the right to vote. The famous abolitionist Sojourner Truth was a well known speaker and advocate for full suffrage for both men and women. She was not only a nationally celebrated abolitionist, she was also a strong advocate of women’s rights. Although she lived until 1883, Sojourner dictated her story to Olive Gilbert in 1850 in a short summary of her early life.

Post-Civil War history is replete with women who were at the forefront of the freedom struggle. Prior to the 1964 Civil Rights Act, one of the bravest and best known women warriors was the journalist Ida B. Wells whose writings speak for a generation of those who struggled against the vicious lynchings that were negative hallmarks of southern society throughout the 20th century. We should all celebrate and read the work of Ida B. Wells.

By the fifties, with the advent of the modern 20th century Civil Rights movement, we have many examples of women warriors working in various fields too numerous to explicate in this short survey. However, know that from space exploration to daily struggles here on the ground, women such as Rosa Parks and many others led the way.

I will conclude this literary overview with four essential books. These books are autobiographical and feature the words and voices of their authors who were leaders in their respective fields of work.

In 1966, at the continuation of James Meredith’s March Against Fear, SNCC head, Stokely Carmichael shouted out the phrase “Black Power”, which quickly became the goal of Black citizens to gain political and economic power. There was no smooth road, nor any guarantee of success, nevertheless, Black youth in particular, enthusiastically took up the cause of gaining and using power. As always women were both key leaders as well as foot soldiers in the freedom struggle.

One person who played a critical role as both an adviser and activist was publicist and organizer Florence Tate. Her memoir, which was completed by Jake-Ann Jones, details the exhilarating breakthroughs as well as the debilitating depressions that the struggle entails. Not only is Florence Tate’s story both enthralling and insightful in its own right, her life work includes birthing and rearing, along with her partner, Charles Tate, the noted and recently deceased musician and cultural critic Greg Tate.

Florence served as press secretary for Jesse Jackson when he ran for president of the United States and also was critical to the first term of the Marion Berry administration in Washington, D.C. Additionally, Florence had been a strong supporter and advocate for UNITA, the Angolan liberation organization, until she broke with them over internecine fights within UNITA that led to the death of a number of leading members. When Florence became convinced that Jonas Savimbi, the nominal leader of UNITA, had gone mad and drunk with power, she left UNITA.

Although suffering from clinical depression during key parts of her life, Florence Tate does not shield nor shy away from relaying aspects of her personal struggles. In fact, what is important about her narrative is the honesty and forthrightness with which she outlines the ups and downs, the twists and turns, and even the contradictory elements of her long journey. This is an important statement for some one who was a front-liner in the liberation struggle both here and abroad.

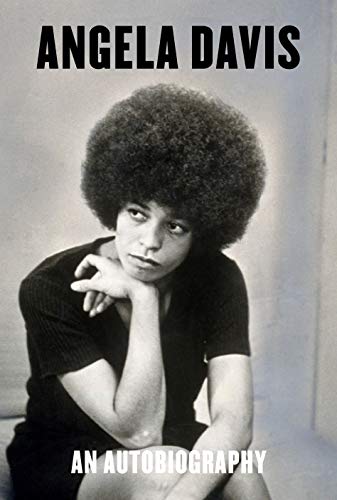

Of course I felt duty bound to read Angela Davis’ book when it first came out. Back in the seventies she was perhaps the best known in a long line of women who were instrumental in the advocacy of what Malcolm X had defined as our human rights movement. She was particularly sharp in analyzing and in organizing opposition to mass incarceration.

Worldwide, the United States was number one in the incarceration of its citizens. In the U.S., Louisiana was number one in terms of incarceration and in Louisiana, New Orleans was number one. Although the specifics differ from decade to decade, New Orleans is an epicenter of incarceration. Although the majority of prisoners are not housed within the city, they originally come from New Orleans.

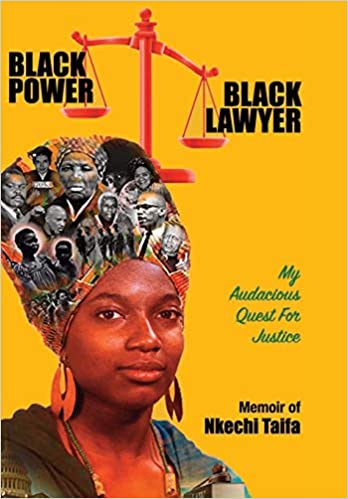

Another important memoir is Black Power Black Lawyer by Nkechi Taifa. In her video interview, Nkechi offers us a true perspective on the protracted liberation struggle, especially the various movements such as the Black Panthers, the Nation of Islam, the Civil Rights struggles, the Reparations movement, and the Black Lives Matter movement.

As a lawyer, Taifa was dedicated to the effort to reform criminal justice. She is a founder of the Justice Roundtable, a broad network of advocacy groups advancing progressive justice system reform. Her book is particularly instructive in terms of putting forward the motives and movements of major activists of the late 20th century.

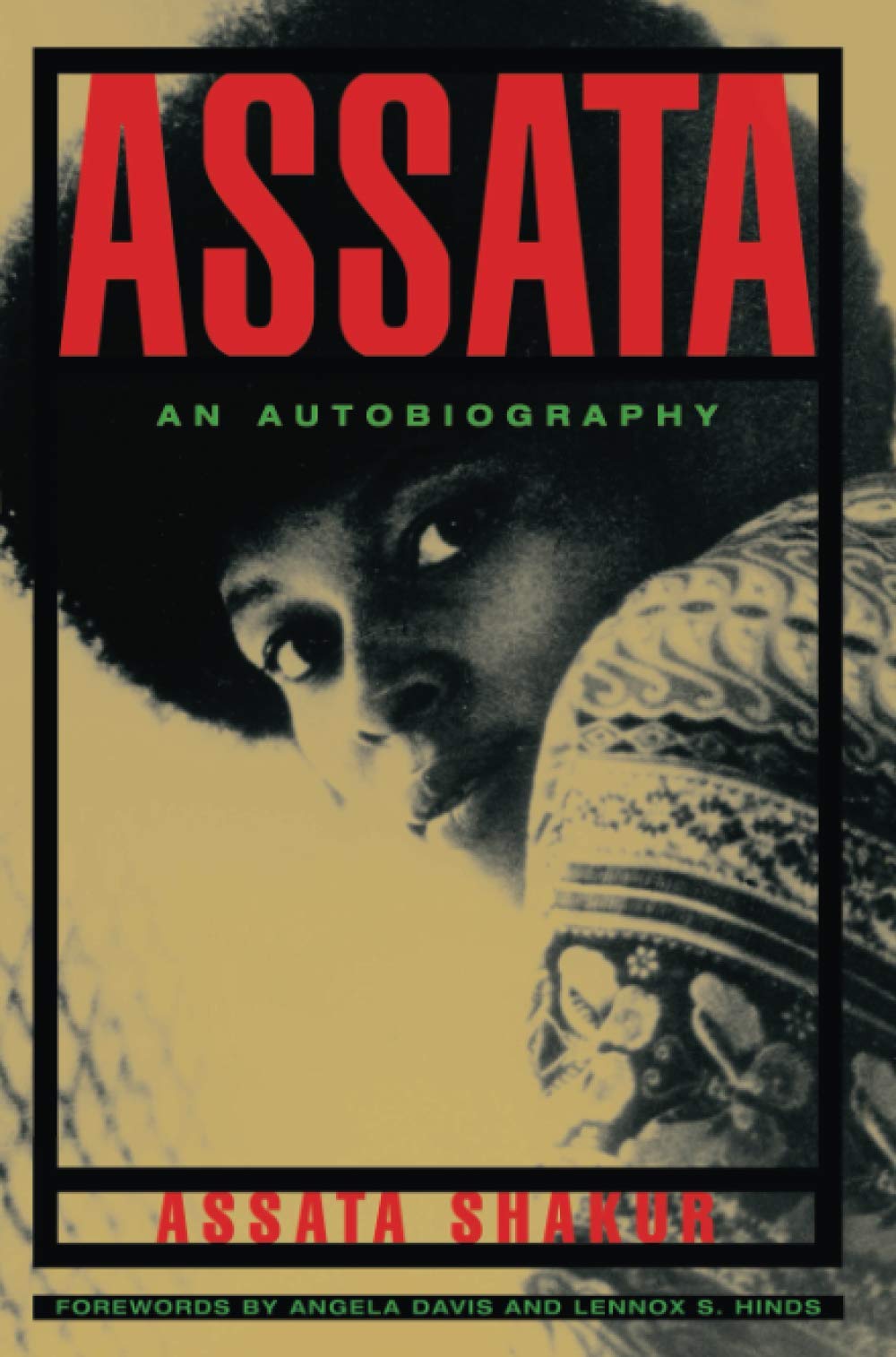

For me the major woman warrior who has written a book is Assata Shakur. Assata details her development as an activist, and eventually as a revolutionary. She was shot, hospitalized and incarcerated but eventually was liberated in a bold jailbreak operation.

However and amazingly, before she escaped, while she was in court, she conceived and subsequently birthed a child while in prison. She describes all of this in her book. Assata lives today in Cuba, which is where I met her at a conference.

I make it a point to at least greet people even if I don’t know them personally. At a break in our session, as I was walking down the aisle, I saw this sister sitting alone, off to the side. I spoke, “Hi, my name is Kalamu. How are you doing?” I don’t speak Spanish. I didn’t know if she was Cuban or even if she spoke English. I just waved and continued walking on as I heard her reply, “Hello. My name is Assata.”

I stopped, turned around. “Assata Shakur?” She smiled and simply said “yes”.

Long story short, we struck up a conversation and we ended up, not only engaging in a brief exchange, but we also got together over the course of the conference. She wanted to know about what was happening in the states, and me wanting to know what was life like for her in this revolutionary country that was at political odds with the United States.

When I got back home, some months later I wrote a long prose poem about Assata. Later, we introduced her book to students in our high school Students at the Center (SAC) writing program. We encouraged our students to detail the story of how they became whomever they are. We asked them to delve into the particulars of their development, to probe and critique the forces that shaped them. Assata’s memoir was instrumental in this method of instruction as she is clear that she did not come out of her mother’s womb thinking that she would become a quintessential woman warrior.

Through reading her book, our students understood what Assata did, and also understood that we all can be active participants as we grow and make life choices. A luta continua–the struggle continues.

= = = = = = = = = = = =

1.1

I’m not afraid to die but I am afraid I’m going to die. Afraid that, outside of a grave, there will not be one square inch of earth on which I can reside; afraid that my enemies will not allow me to breathe unless concrete and steel coffin me; afraid that this sweet island, which has been my sanctuary, will be curdled into a tropical casket.

1.2

For we who have been political prisoners, long term incarceration in modern Amerika is a certain death—it is not like South Africa’s Robben Island where a number of movement men came out stronger, and it is certainly not the same as for those who go in unconscious and fly out as dragons both their wings and their fierceness engendered by the education and self-education that one can extract from the school of captivity. No, I am thinking about those of us whom they want not merely to confine and control, but those of us whose spirits they want to thoroughly crush; we are never released from prison unscathed—if we escape that is different, but if they release us, our freedom inevitably means the authorities have successfully, in some nefarious way or another, reprogrammed us to accept the world as they have constructed society or to either self-destruct in fits of rage or in spasms of insanity.

I know what I am saying. I know Huey Newton was never the same after prison. I know many of my comrades who remained there for ten, for twelve, for twenty years, I know if and when they are released they are deranged even if they really believe they are still ready for the revolution. I would never publicly give the government the satisfaction of recognizing such effectiveness, but I know there is no life after prison for people like me. The mind games, the chemicals they feed us in substances they claim is food, the constant dehumanization of strip searches: fingers forced into your everywhere, beneath each fold of flesh, piercing each cavity. And not just the dignity stripping of naked meat inspection, but also the simultaneous twisting of the ephemeral web that is one’s consciousness, one’s sense of self. Literally who we are becomes different after we have been systematically and scientifically fucked with by experts at mind games.

1.3

So you see, it was either escape, which I did, or die.

I am a runaway slave in an era when the descendants of slaves are well paid in the employ of both consuming and perpetuating big house fantasies. An era where living on the edge seems totally nonsensical, totally unnecessary to those reared on television and cyberspace, corrupted by creature comforts as seemingly innocuous as fast food hamburgers and video games, sports events and evangelical churches.

The mantle of conformity fits us so snugly that those of us who choose naked resistance rather than wear the weave of exploitation, we appear to be no more relevant than homeless bag people existing on the fringe of society, scavenging to survive as we mutter incoherent inanities about how bad the good life is.

Indeed, the guardians of good times tell everyone that not only are we maroons crazy, but worse, because we refuse to join the parade of collaborators with the status quo, we are painted as failures who are afraid to grasp the success that is available to any and all of us who would pledge allegiance to taking advantage of others.

And where can I run to now that capitalism is global and the liberated zones are nearly all paved over and billboarded? If Cuba goes under where will I be able to stand tall? What other country would endure the economic whippings administered to anyone who shelters me? What other nation would (or could afford to) refuse the bounty the government of my tormentors offer for my head, my body?

1.4

Though I rose from the dead once before, I do not believe in miracles. I do not believe if they entrap me this time that I will be able to live within the grip of their murderous clutches.

My strong instinct for survival, so strong at times that I have done what the normal person can not even imagine, indeed, I have done what I could not imagine, I have done whatever was necessary—and you know that necessity is unsentimental and often very, very ugly, if not sometimes downright amoral. My strong instinct for survival will not allow me to be locked down by them and turned into a person who accepts the status quo, or worse, a person who insanely (and ineffectively) rages against the dark of 24-7-365 nightmares.

After all is said and done, I am a human being who loves life, the beauty of quiet moments, the joy of conversation and sincere touch, the exhilaration of sweating as I labor, as I make love, as I exercise. My instinct for survival is no impulse merely to breathe, my instinct is to live, to love life freely and to be free to love life, and I will never accept slavery no matter how comfortable.

* * *

2.1

she followed instructions. got out with her hands up. and then the world exploded. she was on the ground, bullets in her. and she did not really know what happened.

a person caught up in the chaos is the most unreliable witness there is.

perhaps if she had been the bullet, she might have seen the whole scene more clearly, or if she were the gun, she would have known who the targets and who was calling the shots. or if she had been the finger on the trigger she might have known the time table, the sequence of events, but she was only the target, and before she was struck had no warning that the bullet was coming, after all, as the medical experts testified at her trial, given her wounds there was no doubt her hands were up in the gesture of surrender, she was following instructions.

she was not the bullet. so at that moment she did not know it had entered her torso, missed vital organs, and ended up lodged near her neck, leaving a mess of rented flesh in its wake, thin streams of thick blood seeping from the open door of the entry point.

nor did she know that the first bullet had a companion who followed closely on its heels like a younger sibling trailing an idolized big brother.

the impact of the first slug spun her around like a rapist sadistically intent on anal penetration.

the second bullet burrowed into her back.

immediately afterward, in the distance she could hear noises and voices. and thankfully so, for although the voices sounded muffled like that time as a child she had an ear infection and her mother poured some heated liquid in her ear and then plugged it with cotton and all day she kept loosing her balance and asking people “what did you say?” she was thankful because at this moment it was strangely comforting, reassuring even, to hear the words “she ain’t dead yet” and to know that the “she” who was alive was her.

2.2

life is full of choices, most of them are minor, trivial details and inconsequential chains of events, but kernelled in the ordinary are those little nodes on which turn one’s whole existence. why would an assata surrender? perhaps she did not see herself surrendering. perhaps this was just a momentary hassle, a stop and delay tactic. perhaps her gesture was meant to be a diversion. who knows. life is like that. sometimes we ourselves don’t know what we are doing even though the doing will have profound and far reaching consequences. who knows. how can anyone know the future?

2.3

the discovery of the future is always an evaluation of the past. we only learn what the future means once it is over, once we have experienced it, once it has become history. and by then it is too late to change anything. we can never fully know anything, least of all exactly what we did and why. our ability to sense reality is too limited to take in everything. we can only ever grasp a small part of the totality of our existence. the trooper with the gun drawn, barking orders, at that moment what was assata thinking?

2.4

have you ever faced a gun beaded on you, an enemy hollering at you? do you know what you would do if you were shot and on the ground, or in the hospital chained to a gurney, or even in a courtroom and lie after lie after lie after lie was going on record against you, and the judge threatens to throw you out of the courtroom if you don’t be quiet, and every fiber of your being is quivering with the urge to resist, even though enchained, even though guards are over you, and what do you do?

assata was removed from the courtroom and her comrade too. they were shunted into a side room while the trial proceeded and during that isolation they made love.

your enemies are kangarooing you to an almost certain death sentence or at least life imprisonment and you make the decision. to make love. think about choosing love as an act of resistance at that moment. then think about the bravery to make love.

you are a prisoner. on trial. armed agents are standing just outside the door. most of us would never even have thought of making love. and very few, very, very few of us would have had the bravery to bare our nakedness knowing that at any moment the guards could have busted us in the middle of getting it on.

oh, the adrenaline rush, to steal the sweetness of sex under such conditions. now if there was ever a definition of revolutionary fucking, that was it.

2.5

but every act has its consequence. every movement carries us somewhere else then where we were when we started. and sometimes we think we are ready to travel, but we really don’t have a clue as to the magnitude of the trip we blissfully, or blithely, or unknowingly started on.

did assata know that she would become pregnant?

how many times did they do it in the dock?

and now it is decades later and kakuya, a girlchild, has grown up without the emotional anchor of a father’s familiar words, without the rudder of a mother’s daily teachings. a daughter has been reared by extended family. did assata reckon on that? of course not. sometimes we throw our rage at the state without a thought of where we will be thirty years later, who we will become, how our actions will affect those not yet born.

* * *

3.1

I am a warrior and I tell you I hate war. There have been so many times when I have had to go one on one with despair, and it was not always a given that I would win. Sometimes I battle day after day, other times, rare times, I have whole weeks, occasionally a month or two, when I am good to go, well, at least I am ok with being on the periphery of normalcy. My daily diet is the stress of uncertainty.

I know life back in the world is different from when I went underground. I know my people seem freer and hence less consciousness—the intoxication of options, the addiction of material acquisitions, the disorientation of commodification. People even come to Cuba for a vacation. A photograph with me becomes a trophy. It is hard not to be bitter.

3.2

The struggle has become so convoluted, so complex. I can understand the seduction of comfort corruption… even these words seem like so much political rhetoric.

When I was locked down, I kept myself defiantly alive, poised to escape. Now that I have escaped, I find that I am still in captivity, a qualitatively different captivity, a captivity where my range of motion is, of course, much, much wider, my ability to speak out significantly broader, and certainly my opportunities to love life infinitely greater, but I can not fool myself… as long as those who measure life by counting possessions and grading bottom lines are in charge of most of the earth, I remain either in captivity or on the run, never surrendering, constantly resisting, measuring how alive I am by how long, how well I am able to fight until death. What a hard way to live… but this is my life. My. Life.

* * *

4.1

the embargo is real. some times sanitary items are non-existent. there is nothing romantic about resistance. nothing romantic about the grind of constant vigilance, ceaseless struggle. romance is idealism. resistance is realism.

if you read about the struggle many years after, when victories are celebrated in textbooks, when most of the ugliness is erased, when the human costs are barely reckoned or recognized, if you only read about struggle then you can think of its beauty. but the runaway often literally stinks; they do not have the daily luxury of bubble baths or clean fluffy towels after a long, hot shower. the vegetarianism of a subsistence diet of beans and rice, or beans and tortillas is not a trendy choice. very few relationships last a life time in the field, or perhaps, that is the more brutal truth, such relationships only last the shortness of life in the field—life on the run is seldom very, very long and elderly runaways are rare.

people nostalgically talk about the good old days when the political struggle was on fire in the united states, but how many people are rushing to cuba to volunteer to live in exile with assata? we all like to dream, to fantasize about being heroes and to romanticize those individuals whom we consider our heroes. but, oh, the reality of being a runaway is a state embraced by only a very strong few, only a few, very, very few… while the rest of us rationalize about choosing to remain cocooned in the materialism of our relatively comfortable captivity.

—kalamu ya salaam