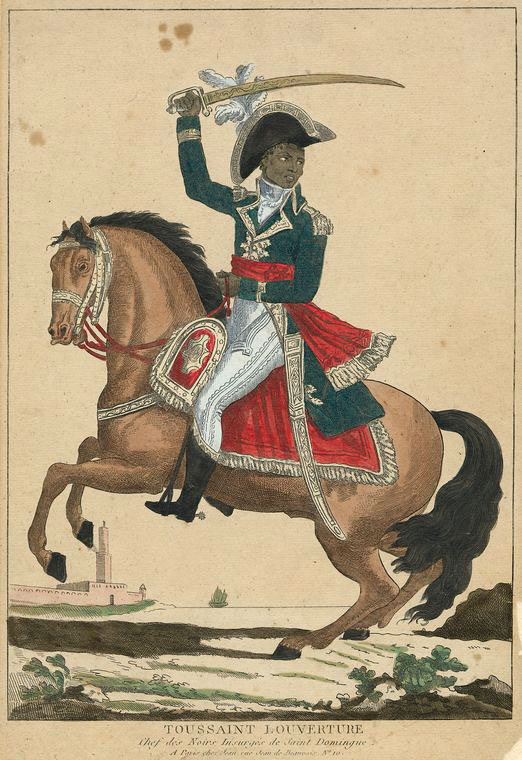

Painting by June Beer

I was walking down a dirt street. Seemingly from out of the blue, I hear someone call to me. In English. “Kalamu! Kalamu!” As the man got closer I recognized the shouter. It was SNCC veteran, Willie Ricks. As we embraced each other, almost simultaneously, we each queried the other, “man, what are you doing here?”

Who in the hell knows I’m here in the northwest of Nicaragua, the city of Esteli, maybe about 150km (roughly 94 miles) away from Managua, the capital, where I flew into the country. Eventually I would visit Bluefields on the Atlantic coast.

Bluefields has a large African heritage population. There is where I met activist and politician Ray Hooker, who was recuperating from wounds he suffered in a recent armed attack.

Also in Bluefields, I just showed up at the front door of largely self-taught painter and poet June Beer. I did not know much about her and she certainly did not know anything about me, but there we were face-to-face. She invites me inside and we engage in a short tete-a-tete. I, of course, learn more about her when I return to the States. She is one of literally thousands, if not millions, of our people who, out of their sheer will to go far beyond simply surviving, decide to do something significant, especially culturally in the arts.

June’s life story reads like a Spanish language tele-nova television series, except that her life was real life, with all the ups and downs we invariably suffer as we bend, and even sometimes break, the bars restricting our life conditions, while we undertake daring efforts to leave a positive Black mark on the world.

Painting by June Beer

On the opposite side of the country, I visited Leon, an old municipality located near the Pacific coast side of the country. Leon is the second largest city and, early on, had been the capital. Although I don’t speak Spanish, I was comfortable everywhere.

In Rama, a city located not too far from the center of southern Nica-Libre, as some of us fondly referred to the country newly liberated by the Sandinistas from the Samoza-regime, I was greeted by a woman in line in front of me. We were waiting to board the ferry that would take us up river to connect to a road that led to Bluefields.

I could not explain to the woman that I was not who she thought I was. My traveling companion, who did speak Spanish, had gone to purchase our transportation tickets. Eventually when he returned and engaged the woman in an animated conversation, she looked confused as he patiently explained who we were and that she was mistaken. I was not ignoring her by saying “no habla Espanol”–I didn’t speak Spanish. She was incredulous as she insisted she recognized me. She knew me and couldn’t understand why I was not talking to her.

I am a big Black man. Tall (five feet, eleven and a half inches) and stout (I easily weigh over two hundred pounds). Although this was my first and only time in the country, I had many of my preconceptions of Central America forever shattered. Prior to arriving, I never would have thought that I looked like a native Nicaraguan.

I spent about 18 days wandering around the war-torn country.

The first Sunday night during an assembly in Managua, I was in a small group that was sent north. Another group was sent south–they eventually were captured by the contras. Our travel was not a typical tourist adventure. In one small town the only two buildings that had been attacked were the school and the medical facility. It’s one thing to see newsreels and television reports, it’s quite another to hear gun battles in the night and sit in or walk next to buildings freshly pock-marked by bullets.

Near Esteli, our group was led by a handgun toting interpreter as we traveled by bus. In one church-building that served as both a school and community center, there was a poster on the wall picturing a man walking a road armed with a rifle. I asked the priest wether it was appropriate for the church to have a poster depicting an armed individual. The priest replied the people had a right to defend themselves. That was one of the major definitions of what “appropriate” really meant: self-defense.

Although I had been in the army, assigned to a mountaintop base located about fifty miles south of the DMZ in South Korea, I had not been involved in actual combat. Indeed, my MOS was electronic maintenance of the Nike Hercules Nuclear Missile, which included arming the warhead.

I was qualified with the forty-five automatic handgun, the fifty-caliber machine gun, and the M-79 grenade launcher, in addition to my training with the standard issue field rife. Moreover, I had been sent to a special school for chemical, biological, and radiological warfare. I was an intensively trained cog in the international killing machine of the U.S. military.

Eventually, after my discharge, I traveled worldwide both as a journalist and/or as an activist. I felt emotionally comfortable everywhere I ventured: dancing in the streets of Rio in Brasil; walking the roads throughout numerous Caribbean islands, including Barbados, my personal favorite, but also St. Lucia, Martinique and Guadalupe among diverse others.

Trinidad and Tobago deserve special mention. Tobago was almost idyllic in it’s peacefulness and unsullied beauty, whereas the hustle and bustle of its big brother island, Trinidad, was almost like comparing New York City to a little family farm in Virginia.

Oil-rich Trinidad is, of course, widely celebrated for “steel pan” music. Once I experienced “Panafest”, I developed a deeper appreciation for how used oil drum containers had been turned into melodic/percussive instruments. The music they made was more than just a one-note wonder. They did everything from classical music, at an extremely high level, to popular music and jazz, and of course calypso.

As a music producer and event organizer, I was one of the people responsible for putting together the initial Pan-Jazz Festival, at which the reigning pan king, Boosie Sharp, traded improvised exchanges with trumpeter Wynton Marsalis, who also excelled at both jazz and classical music–in their improvised duet/battle neither man could totally best the other.

A notable excursion I really looked forward to was a trip to the South American country of Suriname where the official language is Dutch. Before we had the opportunity to travel inland, our visit was curtailed by an attempted coup that was successfully suppressed. Even amid bomb threats at the hotel and people literally jumping out of ground floor windows to escape potential explosions, which, thankfully, did not come, I totally enjoyed my brief stay there.

Without exaggeration, Suriname struck me as being akin to the mythical garden of Eden. When we visited a small island in the middle of the major river that flowed pass the capital city of Paramaribo, we were able to pick up succulent fruit off the ground or hanging from the abundant trees. I remember plums and all types of citrus plus many tropical fruits. I’ve always wanted to return but, alas, never did.

My travels in Suriname, Brazil, and throughout the Caribbean islands were facilitated and, on numerous occasions, made for a deeper experience by the intercessions and friendship of my dear brother, Jimi Lee, who became not only a valued guide and a man who shared his many human connections whenever and wherever we ventured forth.

Jimi was a trusted partner in diverse situations and far ranging excursions that otherwise might easily have gone sideways. My ramblings certainly would not have been half as fruitful were it not for Jimi’s knowledgable care and concern. He introduced me to socially important activists, organizers and situations that were previously unknown and unimagined by me. Moreover, as we traveled together, he always looked out for me, who was both a stranger and at the same time an insider in too many instances and situations to be named.

The first independent Caribbean country to significantly break ties with Europe holds a special place in my consciousness. I was on my own as an observer and at the same time enjoyed broad access as a journalist throughout French-speaking Haiti, a country I can never forget. I was especially impressed by the famous Citadel that was built perched atop one of the highest mountains and fitted out with cannons to protect the country should the French decide to counterattack in a vain effort to reclaim that fabled country after the successful uprising in 1804.

Historic Landmark France Citadelle De Corte Castle

The Citadel was a marvel of engineering and human effort. How the victorious peasants of Haiti successfully constructed the Citadel at the start of the 19th century we will probably never know. That fortress undoubtedly is one of the wonders of the world.

On a different occasion on a different island, one of the vice-presidents drove us through the Blue Mountain ranges of English-speaking Jamaica, a part of the country internationally famous for its coffee but also the historic home territory of maroons who escaped enslavement on Jamaica’s plantations.

Once we descended to the north coast, we paused briefly for a lunch-time, pit-stop nearby the popular Blue Lagoon.

Although I enjoyed the length and breadth of my worldwide travels, I really marveled at and was enchanted by the Casbah-like marketplaces of Zanzibar and especially the sparkling blue-green waters of the Indian Ocean. In Tanzania’s major port city, Dar es Salaam, the activist in me could not resist standing astride the tracks of the then recently completed Tan-Zam railroad, which was built to free, copper-rich Zambia from an economic stranglehold imposed by the racist Rhodesian and South African interlopers.

Much further east in the orient, my vision was increased by standing atop the Great Wall of China and peering out over the adjoining countryside. We were shown the palaces and objects of antiquity but nothing matched witnessing literally millions of Chinese celebrating in Peking (now Beijing), the night Deng Xiaoping was rehabilitated.

And of course I should mention the amazing, forward thinking use of technology that was all over Tokyo, Japan, which we visited for a day, both coming and going, during our travel to China. I had previously, briefly been in Kyoto, Japan while in the army. I was wary of the tourist traps, especially for us soldiers, where young women sat at the bars drinking and smoking in an atmosphere of sex and drugs. One quick peep and it was back to the ship for me.

In an entirely different part of the world, I visited a museum in Munich, Germany and had the wonderful opportunity to stare, touching close, at paintings by Matisse, Picasso, Gaugin and others culled from Picasso’s personal collection. Most impressively, visitors were greeted at the front door by a carved head that stood at least six-feet tall, a massive West African statue that left me absolutely awestruck.

At a different time I was in Ghana–my wife was so impressed, she wanted to retire there. We attended the first multi-ethnic festival representing the diverse peoples of the country. Panafest was held partially to attract foreign tourism in addition to helping to integrate and unify the diverse elements of Ghana. While the music, dancing, and related festivities were really attractive, for me, the source of the most meaningful interaction happened when we visited the slave dungeons, known as slave castles, strung out along Ghana’s long Atlantic coastline.

Most people only see these relics of that terrible time during the daylight hours but special arrangements had been made and we were allowed to go down into the holding cells at night with just small handheld candles for illumination. The eerie feeling, the dankness, the uninviting dark, the vividly imagined horror of the conditions suffered by our ancestors marked me in ways for which I was totally unprepared. At one point I fervently remember wanting nothing more than simply to escape the experience.

My impressions of Europe, especially London, where I had extended visits at least four or five times, were far different from the unhospitable moments I had expected. Those sojourns were pleasant and consistently culturally rewarding. In retrospect, I realized that a major aspect of my embrace of the London town visits had to do with a factor that hit me by surprise, although it should not have. Similar to the United States, the metropoles of Europe are crossroads containing diverse African peoples striving to make a livable haven out of seats of exploitative and oppressive hell.

I especially recall walking through the snow one dreary afternoon trying to find a flat in north London where a South African freedom fighter was hold up while on a liberation assignment. Like a moment lifted from a semi-secret private meeting, well into the evening, we sat before a crackling fire and seriously talked.

I congratulated him as I related how important their anti-Apartheid work was worldwide. Breaking into my praise, he shushed me by relating how our civil rights and Black power struggles had inspired and catalysed their work. At that moment I realized that no matter where we were and what were the conditions there, we were engaged in struggles that had common elements. We were distant cousins.

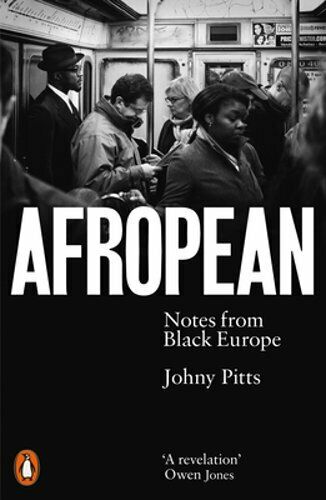

A recent book, Afropean: Notes from Black Europe, by Johny Pitts goes much deeper into the why’s and wherefore’s of Black survival in European environs. While we emphasize political struggles and daily exploitative living experiences there are, nevertheless, also amazing moments of joy, or at least satisfaction, to be found anywhere in the world our people are.

On a different note, as mundane as it may sound, when I managed a band touring music festivals, there was something totally delicious upon eating freshly baked and buttered, French bread in combination with diverse cheese while in Nancy, France. Until I was there, it never occurred to me, that those crusty, long loafs of French bread were not just a stable of New Orleans po-boy sandwiches, but actually had their origin in France. Indeed, an even deeper example of an oxymoron that was actually historically explainable, was that some of the best French bread to be found in New Orleans is actually produced by Vietnamese bakers in their enclaves in a far flung section of the city, New Orleans East, locally known simply as “the east”.

While there was so much to hear, see, feel, smell and taste in parts of the world I had never previously visited, I also had the benefit of my broad travels around the USA, including a cold winter spent in Minnesota, which is where the head waters of the mighty Mississippi River gush forth. I am from New Orleans, over two thousand miles away, located in a bend in the river, just above where the river flows into the Gulf of Mexico.

I have had a wide variety of experiences. My history confirms that people may have divergent cultural practices and languages, but when you get right down to the street level and the daily interactions of people one to another, well, the warping of U.S. imperialism worldwide notwithstanding, people are people. We all laugh, we all cry, we all revere our families and stare, sometimes disbelieving, at the foreign ways of our fellow citizens of the world.

Everywhere I went there was something to learn; something instructive, or important, or at the very least interesting. This travelogue only skims the surface of my memories.

My political activism causes me to have a deep interest in the economic and political underpinnings of different peoples, nevertheless it doesn’t take long to embrace similarities or to successfully struggle to understand or appreciate differences.

Perhaps my most important macro lesson was given to me by Mwalimu (“teacher”–an honorific title), awarded to Julius Nyerere. In a small conclave I literally sat a few feet from the country’s president, who took me by surprise when he imparted an important observation.

Julius Nyerere, President of the East African federation (1964 -1985) of mainland Tanzania and island Zanzibar

“All governments are conservative. . .” I respectfully sought to interrupted him, recounting the anti-apartheid measures undertaken by their country in overt support for liberation organizations throughout southern Africa. Nyerere hugely smiled at my naïveté and repeated himself, slowly and with appropriate hand gestures, “all governments are conservative.”

I learned a lesson that day that I have never forgotten. Whether revolutionary or reactionary, socialist or capitalist, upon obtaining office and practicing real politics, all governments are, or become, conservative.

You can take that to the bank all around the world; power always seeks to consolidate itself. That’s a basic law of science and sociology. Unless acted on by an outside force, governments are going to strive to be whatever they are, and more likely whatever they become due to their efforts at maintaining their status quo. Howsoever it may or may not benefit its citizens and foreign members, the ultimate goal of every government is staying in power.