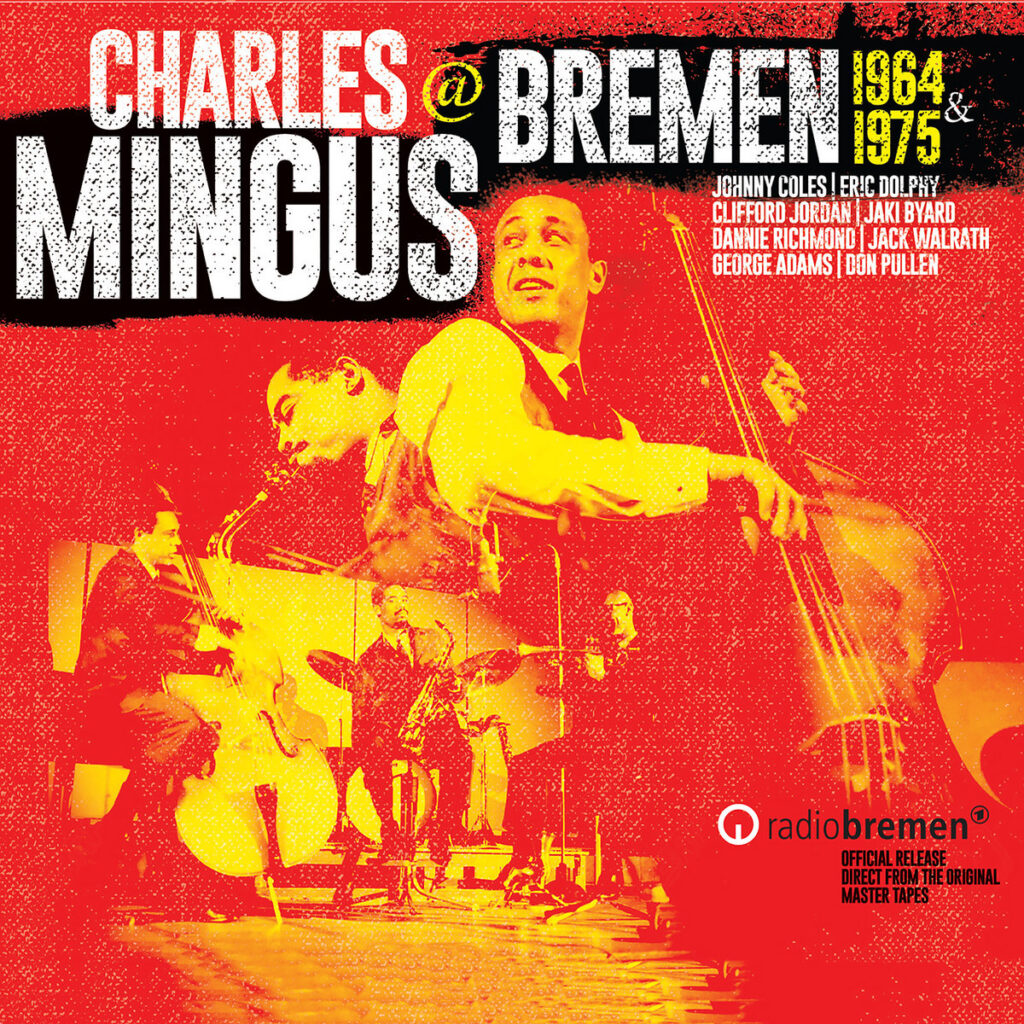

I’m ready to put forward my best jazz album of 2020. None of the usual suspects make the cut. This is modern jazz from the sixties and seventies. Innovative bassist/composer, maestro Charles Mingus (April 22, 1922 – January 5, 1979) and a gathering of beautiful musicians, seriously playing at the height of their powers. Bracing music. Not for everyone–but if you’re into contemporary jazz this is as close to sonic nirvana as you can get in this lifetime. If you have Amazon Prime, the music streams free.

Charles Mingus was both a composer of astounding depth and also a bandleader who reveled in the musical achievements in the moment. Here, in one box set, are two concerts recorded in Bremen, Germany a little over a decade apart–1964 & 1975, two years that I usually short-hand to respectively be the Civil Rights and the Black Power eras.

As a jazz addict I’m a major fan of Trane (John Coltrane), Monk (Thelonious Monk), and Mingus (Charles Mingus). Of course, there are numerous others, but the aforementioned triumvirate are my major touch-stones, those whom I return to time and again for inspiration and aural excellence.

I’ve got to add Duke Ellington as a composer/bandleader and Miles Davis as a soloist/bandleader to that pantheon of significant voices although I don’t think Duke is major as an instrumentalist, nor is Miles profound as a composer. Nevertheless, all of them have canonical albums that have been unparalleled additions to recorded jazz.

All jazz aficionados have their personal selection of favorite players and performances. Moreover, it is well known that it’s hard for studio albums to compare with stirring recorded concert performances. Inevitably, while the studio offers an opportunity to lay down iconic music, it’s in performance that jazz inevitably scales the heights.

Many of the compositions recorded in Mingus’ two Bremen concerts have been recorded in the studio or have concert sessions that are major performances of jazz lore. Previous recordings notwithstanding, this 4-CD set is essential for fans of Mingus’ music.

Here are some of the staggering highlights. First, there is the work of woodwind master Eric Dolphy. His technical achievements as an instrumentalist are the pinnacle of what it means to master the saxophone. I don’t know which brings me more joy: the brilliance of his alto playing or the massive agility and impact of his bass clarinet solos. Less than a month after his appearance on the 1964 recording, Dolphy was gone, died in Germany of a diabetes complication.

Second, there are the two pianists: Jaki Byard and Don Pullen. Byard is encyclopedic in his abilities to cover the waterfront of over a half-century of recorded jazz keyboard stylings. He lays down a multi-textured carpet of chordal work that virtually defines jazz from the twenties to the sixties. Byard truly knows how to sonically embody the sound of hammers on strings, thereby giving us both percussion and melody, singing single notes as well as prodigious chordal techniques. Pullen, on the other hand (really on both hands), can solo to match any of the horn players in his ability to excite rhapsodic and rapturous responses as he pounds and trills the keys. His is a unique vocabulary of pianistic techniques that are as exciting as any horn player achieving anthemic high notes and is also awe inspiring with his dexterous explorations up and down the scales combined with the machine-gun velocity of single-note runs.

I was appreciative of the work of both tenor saxophonists: Clifford Jordan and George Adams. Their recordings rarely reach the intensity of what is displayed herein. Both Jordan and Adams were too often overshadowed by the horn players with whom they played, however both are outstanding on these recordings. I also am particularly appreciative of the trumpet stylings of Johnny Coles and Jack Walrath. It is a special joy to hear the severely under-recorded Coles blowing at length, especially because on a previous recording of the band, Coles was ill and did not offer up his sweetly pungent trumpet essays. How he achieves a seemingly contradictory sound is both stirring and absolutely singular. Walrath is a woefully under appreciated musician. The second concert offers some of Walrath’s best recorded solos and, hopefully, encourages some listeners to check out more of Walrath’s brass work.

Of course, I can not say enough about Dannie Richmond’s bedrock drumming that keeps the music moving and exciting without recourse to bombastic pounding of the skins. Given the vitality and volatility of Dannie’s sensitive support, it is amazing that he is not better celebrated as a master percussionist.

Standing out because of his prodigious command of the string bass is my man Mingus, who was stellar as both an accompanist&instrumentalist and simultaneously as a composer. While Mingus has a number of important albums, this major set of two concerts, is a surprising and important addition to his aural library. If you are not familiar with the recorded work of Charles Mingus, this box is phenomenally satisfying, and if you are familiar with Mingus, this set is a new joy to add to the Mingus banquet of musical delights.

A final footnote: of the 15 tracks there is only one repeat. Both concerts offer up rollicking versions of “Fables of Faubus”, with the ’75 recording presenting us with an update that is shorter but far more sarcastically condemnatory. I hope I have convinced you that this 4-CD Bremen box set is a musical must-have for any of the thousands of fans of contemporary jazz in general and Charles Mingus in particular.