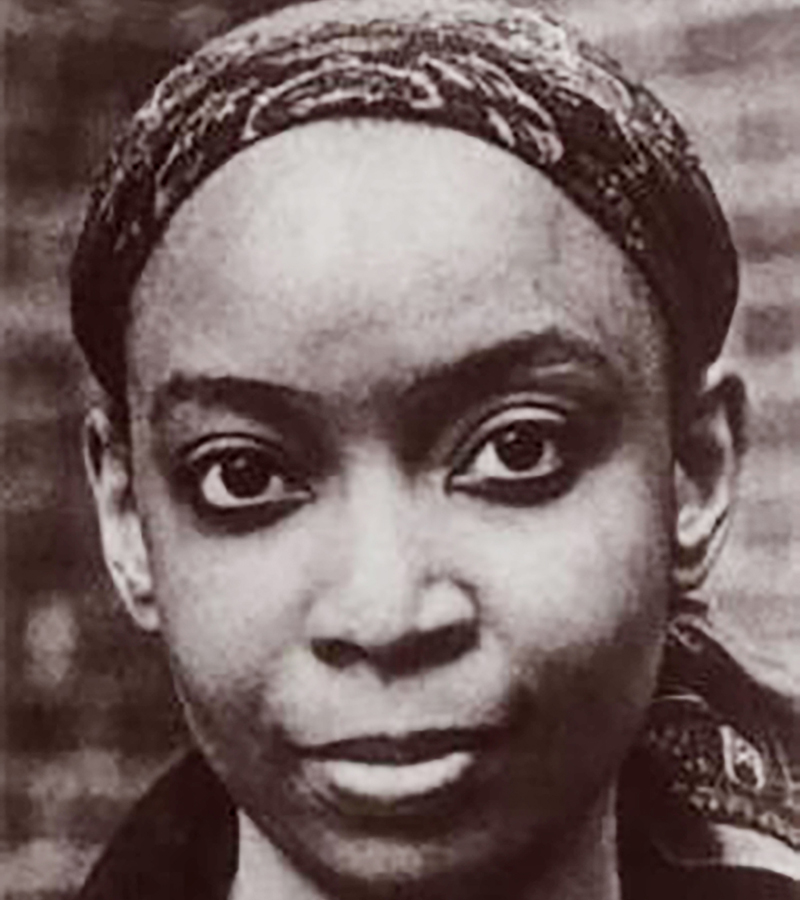

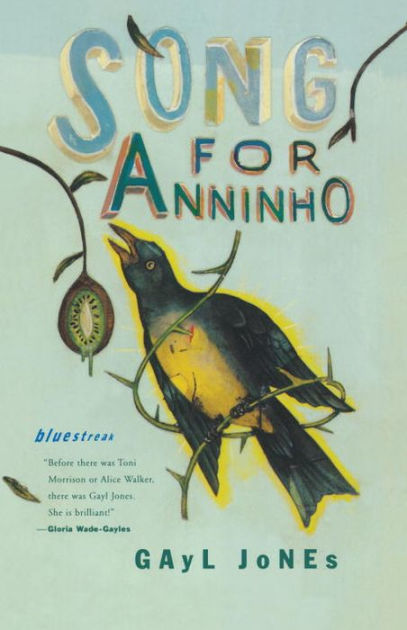

I just read a long look at the life and career of Gayl Jones, born in Lexington, Kentucky on November 23, 1949. Between the end of World War 2 and the seventies culmination of the Civil Rights struggle is a rough period. I don’t know her but I know the road she has traveled. Way back when, long before Katrina tried to drown New Orleans, I read and was captivated by her book, Song of Anninho, chronicling our turbulent history in Brazil, South America. Brazil contains the largest population of African-heritage people in the Western hemisphere, and if I understand correctly, the largest population of our people worldwide with the possible exception of Nigeria.

Gayl is a hell of a writer. Tough and too much. I knew pieces of her story. In combination with my readings and what I already knew, the 2020 Atlantic magazine article, entitled The Best American Novelist Whose Name You May Not Know, by Calvin Baker, pulled the jigsaw together for me. It is a fascinating horror show; I don’t like looking at it but I am compelled to regard the importance of it.

Being a serious, Black writer in America is damn near impossible if the goal is to create great literature grounded in the Black experience and, at the same time, remain sane while telling the truth. That’s a chess game with life; life has both the opening move and, ultimately, the final move where death or resignation are the only choices.

You see great literature requires you to tell the truth, and the truth is most of us don’t really want to hear untempered or unsugared truth about life in America, whether pre- or post- the 1860s Civil War. Especially now that we are recently free of Donald Trump, we all want a happy ending, or at least a hopeful ending, but there is no happiness or hope in death, which is the only conclusion there is for each of us. Gayl Jones not only knows that, she has written stories that contain a small share of happiness but are grounded in death. After all, no matter how well or how poorly we live, in the end, in our ending, we all die.

Here is a tragic thumbnail. Early on she made her mark. Many were struck dumb by her brilliance, more than a few repulsed by her unrelenting assault on optimism about American history and promise, vis-a-vis Black existence in a land that was never meant to be a home other than a plantation.

Plantations are a mean space. Gayl’s writings elegantly albeit unflinchingly inhabit that mean space. Her books, like a Malcolm X speech, make it plain: home is not a hospitable place for African Americans. Especially prescient is her non-fiction book of literary criticism: Liberating Voices: Oral Tradition in African American Literature.

By dint of her imagination, Gayl traveled to Brazil, which is where I came to know her work, particularly Song Of Anninho. After grad school she went to Europe with her husband, Bob Higgins (aka Bob Jones); they eventually returned to Kentucky. Circa 1998, a Newsweek article led to a police SWAT team assault ostensibly on a decades old warrant. Gayl was physically held down by the invading authorities. Her husband killed himself during the siege. He slit his own throat. How do you live after that? Decades later, also in Kentucky, police killed Breonna Taylor. It seems the killings never stop.

Gayl has her masterwork, Palmares, due out within a year. Like I said, being a serious Black writer is serious business. It could get you killed or at least be the victim of unspeakable but, all too often not uncommon, great American horrors.

Although Gayl is still alive, her survival is a wonder. Known as an early seventies purveyor of feminism, she is both a hero and a model to and for many of us. I don’t know how she has survived but I do know I love her. I want to state publicly my support for Gayl Jones.