The real question is “Why?”.

I had news to rip and my 8pm – 10pm Sunday night jazz program to produce. Ripping the news required me to get to the station early. Literally pulled off the roll of teletype news and separated the items by tearing them into manageable strips, which in turn were read on the broadcast news at the top of the hour.

It was February 21st, 1965. A shocking news story: Malcolm X was assassinated. Linda, a young sister from Little Rock, who was with me was crying. I guess I thought I was supposed to be strong and held back my tears. Really my rage. That’s what I was damming behind my stoic exterior. Years later, I was banned from a radio program at WWOZ in my home town. Part of my offense had been to produce a Malcolm X program that included excerpts of his speeches and related music that included Archie Sheep’s homage “Malcolm, Malcolm Semper Malcolm“. (I am listening to it as I write this.) In the eighties that was too much for the managers of our public radio station.

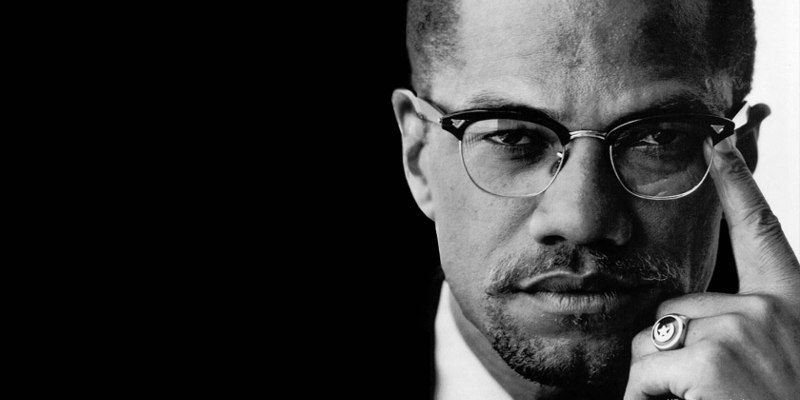

I was sad when King had been shot down but I was emotionally devastated when Malcolm was killed. I was not a muslim, nor a follower of the Nation of Islam. I had been a long-time civil rights worker (sit-ins, voter registration, the whole nine), but somehow Malcolm’s death moved me in ways that none of the other death’s of that era did, including the assaults on both president Kennedy and later Bobby Kennedy.

Why then was I so affected by Malcolm’s demise? I know and I don’t know. I know it was because in those last years of Malcolm’s life he was a walking definition of Black manhood. Malcolm X was a family man, a supporter and protector of women (which was a major reason for his break with Mr. Muhammad). He was someone who made pan-africanism real with his journey across Africa during his trip to Mecca. He was a religious man who did not require a follower to join the religion in which he believed. But there was an indefinable more, a feeling. Like the old r&b song said: I don’t know why I loved him, but I did. There was just a deep affection I had for that man.

One of the most moving sequences is the silent non-responsiveness of Betty Shabazz as she is pummeled with a barrage of media questions following the death of her husband. Her face was not simply sadness. She projected a defiant exterior that refused to breakdown in a moment when she was obviously without hope.

Okay, so it has been years since that deep mourning for the loss of a hero was resurrected in me. And then I spent a Sunday night binge watching the Netflix documentary. The movie features the gum-shoe, tireless sleuthing of Abdur-Rahman Muhammad, the man who single-handedly took on the task of finding out the answer to the questions: who killed Malcolm X and why did they do so. The program offers both a theory and an image of the killer, but there is no pat ending. Indeed, there is a conundrum and a contradiction that the documentary does not shy away from exploring.

You might not be as moved as I was, but if you watch the images (there is more live footage than I ever seen before), listen to his words, agree (or disagree) with the analysis, you too will be affected. This is what cable could/should do that the networks never would for a number of reasons.

Major stations would never broadcast hours and hours of Malcolm X (6 episodes, 43minutes each)–in the words of Bobby Womack singing about what recording executives told him: “it’s not commercial”. And perhaps a bit too educational for PBS. Or maybe not, but PBS didn’t put up the funds for this production that included not only historic images of Malcolm X but also has raised questions that are causing re-evaluation by criminal authorities.

We owe it to our ancestors, to our future progeny, and to ourselves to watch this documentary, which ought to be required viewing in every American history class.

Thanks for the info will pass it on. Reparations and Repatriation!