Dealing with our history is difficult. Why us? Or, in the words of that hell of a difficult question that Pops posed to all of us: “What did we do to be so Black and blue”?

What indeed. Understanding history requires more than most of us are capable of giving. Why is that? Why are we who we are? There is no simple answer.

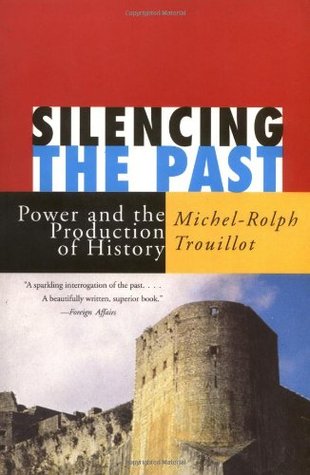

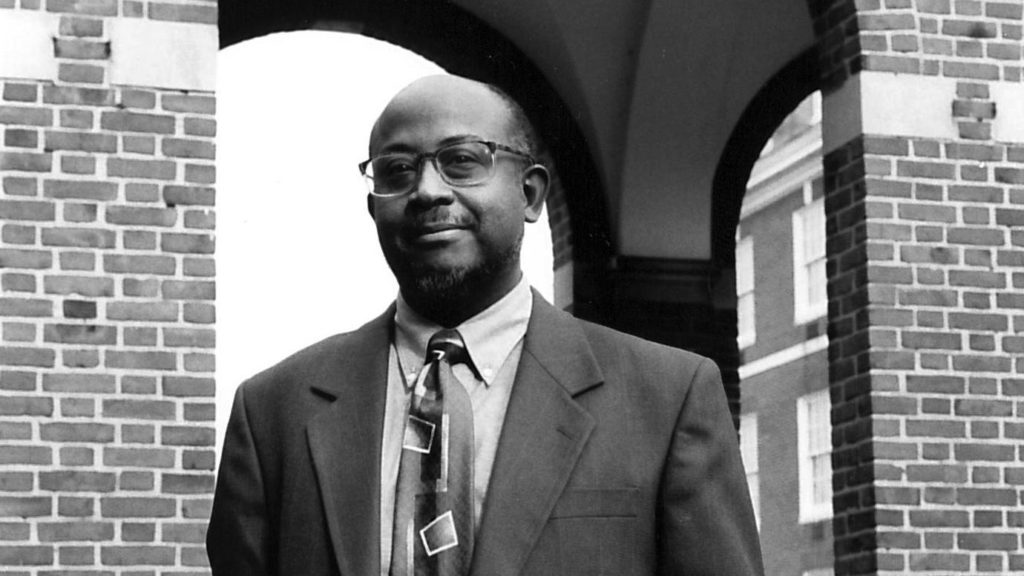

No straight forward way to get to understanding ourselves and our condition. Much of our conundrum is detailed in Silencing The Past, an uber-important scholarly work by Haitian scholar Michel-Ralph Trouillot. His last post was at the University of Chicago, where he died of a brain aneurism on July 5, 2012.

As I plowed through Trouillot insightful work, I frequently found myself referring to a dictionary, but despite my difficulties I persevered because the ideas about grasping history were so provocative.

“The Three Faces of Sans Souci” is the second chapter in his challenging study. Each face taught me different aspects of my history that were heretofore unknown to me in their fullness.

First, there was the town at the base of the mountain where the monument was located and through which water flowed keeping the stone edifice cool even on the hottest day. Then there was the European Prussian palace named Sans Souci-Potsdam. Finally, there was the Haitian leader Sans Souci.

I had stood atop The Citadel, and was faintly familiar with the European/Germanic connection through reading a smattering of historical works, but all my travels and reading not withstanding, I had never before heard of the soldier named Sans Souci.

Perhaps because I had been there I found myself enchanted by both the complexity and beauty of Trouillot’s examination of the Haitian revolution through focusing on the long neglected gathering of stones at the base of the mountain atop which sits The Citadel, the supreme monument of Black history in the west, built by Haitian revolutionary freedom fighter Henri Christophe.

Many years ago, in the latter part of the previous 20th century, I had taken a long and twisting mule ride to the summit. When we started out at the bottom I saw a peasant woman with a tray perched atop her head. She was walking up the mountainside. We lost sight of each other when she shoved ahead in a direction that diverged from our mule path. Just before we reached the top over a half hour later, she reappeared. Ahead of us! At that moment, I viscerally understood the power of the Haitian revolution. Fully comprehended how our 19th century ancestors had whipped the French, outwitted the English, and successfully dodged brutal Spain. How the formerly enslaved became the progenitors of this world’s sole successful slave revolt. It was because of their physical persistence, the persistence of blackness.

Without saying a word, they climbed the mountain, pushing forward, trodding one foot in front the other. They refused to surrender to seemingly superior forces. Their stubborn Haitian hearts enabled them to succeed. That same stubbornness is necessary if we are to survive the crisis of the 21st century, i.e. the dominance of U.S. modernity.

Going to the mountain top is a familiar trope of African American culture. While reveling in and rejoicing about our history of struggle, most of us do not realize that the bulk of our history was constructed by the so-called wretched of the earth, by illiterate and semiliterate peasants who kept on keeping on.

We may ride astride modern mules today, but we should always remember it will be the least of us who enable the totality of us to reach the pinnacles of whatever future mountains we face. Silencing The Past, in both its intellectually challenging complexity and its historically significant insights, offers us the opportunity to understand and answer the “why” question of our existence.

We are here. The mountain is here. The example of our ancestors teaches us, we are capable of reaching the top if we choose to climb. Because of the hearts of our ancestors, their persistence, their refusal to surrender, that is the answer. Our ancestors are why. Our answer to the question. “We can” because “they did”. We are because they were.

They were. And because of them, we can be.

Indeed a strong testament to a great people

Yes!