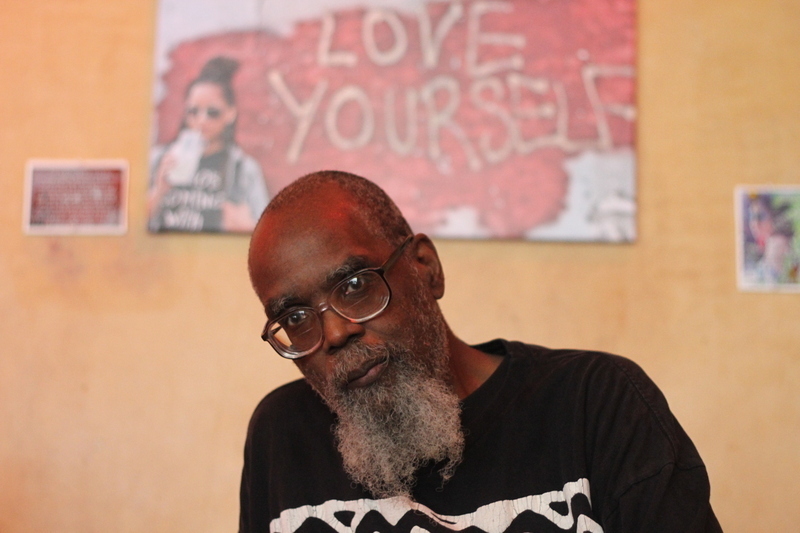

photo by Cfreedom

Flying The Red, The Black and

The Green Flag of Liberation

In the Spring of ’69 the revolution had smashed full force into Southern University New Orleans. We had taken over the school. Literally. We ran everything. Actually continued the classes and full day-to-day operations. But the nominal administration had no say so.

When we first took over we didn’t simply barricade a building and issue a list of ten demands. No, we were much more sophisticated. We marched into the administration building and one by one ran off the administrators, installed students in their place, and ordered that the school would keep on functioning but with a new and revolutionary leadership.

Two specifics will suffice to illustrate my point. When we went into Dean Bashful’s office, he was understandably outraged. He refused to move. So I motioned to a couple of the brothers who literally grabbed the dean and the chair he was in, lifted both from behind the desk and wheeled his ass on out into the corridor, slamming the door shut behind him. We then stationed two stalwarts on duty with orders not to let Bashful back in.

Second, we called the state government in Baton Rouge and told them we had taken over the school and would be in charge until new terms were negotiated and if they didn’t believe us, call back in five minutes and we would answer the phone. We had, of course, already commandeered the switchboard. When Baton Rouge called back, we answered with our same list of demands.

Some people thought they would just send in the police and force our hand but we knew differently. We had already had a major showdown with the police involving literally hundreds of students when we took down the American flag for a second time. A bunch of us were arrested but got out quickly and proceeded to organize a campus that was on fire because the police had gone crazy beating and maceing students who weren’t even initially involved in the demonstrations.

Our core leadership was not composed of teenagers but rather of veterans who were returning to school on the GI Bill. A number of us had served overseas, some in Viet Nam. By then, it was no secret, we were armed and dangerous but also extremely crafty. We didn’t flash our guns to the news media and we had made alliances with many of the faculty who were as opposed to the machinations of the administration as the students were.

Our all-male core leadership had been working together since the fall of 1968 and we kept the circle tight, did not recruit new members. We were wary of people who suddenly wanted to hang with us, in part because we were certain that undercover cops were trying to infiltrate. “The Bad Niggers For Regression” was more like a family than a political formation and we kept it that way. Our revolution only lasted two months so we never had to face major problems of losing leaders over time nor of bringing in new people. Questions, such as recruiting women into the inner circle never got raised as we careened through those two months at breakneck speed.

Everything was happening so fast and there was so much pressure on us, so many different forces at work both for and against us. We literally had to shape our revolution in the process of making revolution, there was no time off, no time to reflect, meditate and plan. Seems like it was one crisis after another that had to be addressed immediately with no room for error. Under such conditions, people tend to go with what they know, rely on what worked in the past, only trust tried and proven people.

One of the most profound contradictions of revolution is that during a revolution because events are moving fast and the opposition is fighting fiercely to unseat the revolution, what results is that the revolutionary leadership becomes both conservative and suspicious, unwilling to change itself in any major way and reluctant to admit new people into the core leadership. Of course, the average person lives their life without ever having to direct a revolution.

America was literally on fire and/or smoldering one year after the assassination of Martin Luther King. The winds of revolution were blowing everywhere. You either set sail or hunkered down until the storm passed over. Making a successful revolution is no joke. Indeed, as we quickly found out, overthrowing the old order was easy compared to running a new order. To me, taking over was not our major accomplishment. Our success was in running the school.

Initially we had focused on the lack of resources and the need for capital improvements. For example the library had empty bookshelves. We did not have enough professors to teach the classes we needed. There was no black studies department. We resisted the idea that college was simply supposed to train students to become workers in corporate America. We wanted community development.

Indeed, we did not have detailed demands. The second time we raised our flag of black liberation and the police attacked students and mercilessly beat us down we were prepared to defend ourselves in court but we did not fully realize that our next step was not simply to take over the school but to run the school.

Running the school demanded we create an administration. I don’t remember exactly how it happened but we chose students other than the core leadership to put in charge of day to day operations. Organizing resistance was one thing, maintaining social services a different discipline altogether. For the rest of my life I would be confronted with the contradiction of leading resistance to the status quo and the push for me to become an administrator of a new status quo. At the time I didn’t realize that one of the central contradictions all revolutions have to face is how to effect reconstruction after the overthrow of an existing order. We never got a chance to fully address that issue because we were only in charge for two months, April and May of 1969, but what a glorious two months that short time period was.

When the authorities visited the campus, everything seemed normal but the top administrators knew they were no longer in charge and many of them simply retreated in the face of our forces. One administrator I must mention was the treasurer, I believe his name was Mr. Burns. He took his job ultra-seriously and explained why he wouldn’t let us take over his office. He talked about sensitive financial information about each student and also all the financial instruments and what have you.

I remember looking into his eyes and saw something I had to respect. He knew we had the upper hand, knew that we had evicted Bashful, and also knew, I’m sure, that he didn’t have the force to stop us but he stood his ground and was ready to take whatever we might dish out to uphold his vow to do his job. We had to respect that. After all, he was not our enemy even though he was a functionary within a system against which we were waging war.

So we conferred amongst ourselves and came up with a solution. I don’t remember how thoroughly we discussed it or whether I thought if we did take over the bursar’s office we would have created a major headache for ourselves with the law enforcement officials, who would no doubt be called in if any significant amount of money came up missing. So after a few minutes we returned to Mr. Burns office and told him we were closing his whole operation down. He could lock up everything, put whatever he needed to put in the safe and after securing whatever sensitive materials, equipment and money he felt necessary, he should lock his inner office and take the keys with him. We weren’t going to let him continue running the office but we wouldn’t put anybody in there either. That was the only office on campus we didn’t inhabit. We let it go dark.

I think we shook hands on it, maybe not. But I do remember he was one of the few that looked us in the eye without looking away. I didn’t see hatred or fear in his eyes, and I hoped we looked the same way to him. I may have some of the details mixed up but I’m certain that we worked out an agreement. He was a man of honor ready to face whatever for his beliefs and we in turn were also men of honor even if we were taking over. Our goal was to transform the school, not destroy it.

In the weeks that followed the take over, the school continued to function. We had no argument with the workers at the school, nor with the clerical staff and a number of key people in management. In fact for most of the workers and the faculty, we introduced a measure of freedom to do their jobs as they deemed best. We unleashed the productive force of experienced workers able to make decisions without some chump administrator riding their back. I’m convinced our decisions to safeguard the jobs and positions of the working personnel was another reason things went smoothly.

On one level, if you visited the campus during the take over, things seemed to be ordinary—well, ordinary once you got over the shock of seeing the red, black and green flag of liberation flying high in front the school. Our takeover was an extraordinary achievement. Not only did we keep the baby, we changed the water and kept the bathtub clean. During the whole takeover, on a day to day basis SUNO was functioning as well as, if not better than, it ever had.

The fact that operations proceeded at an orderly pace allowed the authorities to claim that we hadn’t really taken over. Of course, it didn’t matter to us what they said in the newspapers and on television. As long as the flag was flying, it was clear who was really running the school.

Another issue I’m clear about is this: history will not document much about our takeover. The master never gives the full 411 on slave revolts. Indeed, as much as possible they erase the event in the official records. So, I am never surprised when years later scholars, activists and even some progressive historians don’t know anything about the SUNO uprising. They never talk about those days when the lion not only ate the hunter but dared other hunters to come up in the jungle.

And, by the way, “jungle” is a loaded term. If we said rain forest, nobody would bat an eye in disgust or immediately imagine wild animals and savages. So not only does the lion never win in the hunter’s history books, we also have to put up with the indignity of our environments being termed a “jungle.” But then what would you expect from those who imagine that the “woods” and “forests” are a locus of evil—check European nursery rhymes, check Hollywood movies, indeed, check your own imagination—who lives in the woods?

In many, many ways we were not only in a physical battle, we were more importantly engaged in a propaganda battle. I believe the limited success we actually had was partially due to the fact that for the first time in a long time, the “trains” at SUNO ran on time. We received mad respect from students, faculty and staff for the way we conducted the takeover. We were not into revolution for the hell of it. We were determined to improve our school and that’s what we did.

Others may remember these times differently than I do. They can write their own versions of our common history. Ultimately, what matters most to me is that among the people who were there, the students who participated in the take over, there is general agreement—the spring of 1969, those were the real “good old days.”

While everything was cool on the campus, the state had a problem. John McKeithen, who was the reigning governor, had stated often that he was going to return law and order to the campus and that anarchy would not be tolerated. His specific response to our SUNO takeover was that he was not going to negotiate under threats and certainly was not going to visit the campus while student demonstrations were still going on.

McKeithen’s grandstanding was irrelevant as far as we were concerned. We had control of the campus and that was that. Then McKeithen made a gross mistake. He scheduled a public appearance in New Orleans at a church located one block off Canal Street in the heart of the downtown business district. We found out about the time and place of McKeithen’s speech and trapped him.

Our movement was notorious for our instant demonstrations. We would organize convoys and could mobilize a couple hundred students anywhere in New Orleans literally within fifteen or twenty minutes. McKeithen was speaking in a church that had only two doors: a front door and a side door that fed into an alley which ran along side the church but only opened to the front street address. In other words, if you blocked the street in front the church where was no other way out.

SUNO was located at least six miles away from that church and there was no direct route from SUNO to the church. McKeithen was to make a brief speech and then be whisked away, or so they thought. By the time McKeithen had concluded his speech we had over three hundred, chanting students in the street blocking his exit from the church.

The authorities were stymied. They didn’t want a repeat of the mob scene and wild melee that happened when we were arrested for taking down the American flag. We stood around outside in our usual jovial mood—we had the upper hand and we knew it. We even joked with the undercover cops whom we knew on sight, a couple of them we knew by name.

In a weird way, some of the detectives had a measure of respect for us because we were smart, quick and also fearless. They knew we had guns and that we were smart enough not to make stupid or needlessly provocative moves that would have given the police a chance to wipe us out. So there we were approximately ten-thirty in the morning, the streets full of fired-up SUNO students and the governor of the state trapped inside a church.

One of the cops asked me, what yall gonna do? I told him that was not the relevant question. The relevant question is what’s the governor going to do.

At first there was no direct communication. But all kinds of behind the scenes pressure must have been mounted because shortly somebody from the governor’s office came out to “talk.” What did we want?

Our position was simple. We were here to see the governor and we weren’t going to talk to anyone else. Period.

After a lot of back and forth which entailed us rejecting one ridiculous proposal after another, they finally relented and said the governor would talk to us. Pick one or two representatives and we could meet inside the church. No way, Jose. That’s not our style. We have open meetings. Everybody had to be able to hear what was going on. The governor had to meet with all of us or none of us.

The church was not big enough, or whatever. OK. Well, the only solution is for the governor to come to SUNO where we had spaces big enough for a public meeting. Agreed. The governor will meet yall at SUNO. No way, Jose. We are going to go to SUNO together.

I remember the tense moments after we allowed the governor to approach the state limousine. McKeithen’s big, beefy body guards were dwarfed by the press of students—nothing was going to move unless we said so. When it came time to get into the car, one of the body guards tried to push me aside. I pushed back. And for a moment there was a stand-off. We would not back down. McKeithen nodded at one of the guards and the guard let two of us get in the back seat next to the governor. And then we crept off as the student body slowly parted to make way for McKeithen going to SUNO.

This was a dangerous moment. I was not worried about being arrested. We formed a caravan on the way back to SUNO. McKeithen to his credit decided it was better to go to SUNO than to have what they surely would have called a riot.

We had already informed the assembled students of what was going on. Our cars had already begun forming up. The governor was not going by himself. Oh, no. We were going to convoy to SUNO.

The ride to SUNO was both quiet and uneventful, and at the same time tense and anxious. None of us knew exactly what the next step was going to be other than the governor was going to speak directly to SUNO students — bringing McKeithen to the campus was a major victory for us. At moments such as those, you have to be able to think quickly in response to the pressures of time and circumstance. We sat side by side in the back seat, each of us silently trying to figure out our next move.

By the time we got to SUNO, the news media had cameras set up and it was the top of the hour item on all three local networks. McKeithen had vowed he would not negotiate with student protestors and now he was going to SUNO to speak to the students. The designated meeting spot was the school cafeteria. When we walked in a mighty cheer rang out.

McKeithen took one look at the stage and balked. He was not going to get on any stage with “that flag” on it. Everywhere we went, the red, black and green flag of black liberation was displayed. That is how our movement was known and now that McKeithen was at SUNO, the governor was threatening to leave without speaking because he was not going to share a stage with our flag.

As I remember it, there were three flags on the stage: the American flag, the state of Louisiana flag, and our flag of black liberation. McKeithen looked me in the eye and set his jaw in tense determination. If we wanted him to get on the stage, we would have to remove our flag. It was an obvious face-saving move on his part.

My solution to the conundrum was relatively simple. I said, OK, take all the flags off the stage. No flags. No problem. We outfoxed McKeithen. And that’s how Governor McKeithen went to SUNO and agreed to negotiate with the students.

That day he promised there would be negotiations about student demands and we in turn agreed that once the negotiations started in earnest we would cease demonstrations. All the way through the negotiation process, I kept expecting some sort of trickery but after close to a week of meetings an agreement was hammered out. Included in the agreement was the right to fly the black flag of liberation on the campus and that is why today, SUNO is probably the only college or university in the nation where the red, black and green can be raised and flown on its own flag pole in front the school.

There are two flag poles in front the administration building, facing the main avenue that runs in front the school. Alas, it has been years since the red, black and green has flown.

In June of 1969 SUNO closed for the summer and when it re-opened in the fall, over a thousand students were expelled and not allowed to enroll. Our leadership had court orders restraining us from setting foot on the campus. Nevertheless, none of that stopped the movement. Over the next two years there were more demonstrations, including another take over of the administration building.

The Spring of ’69 demonstrations and not been the first nor were they the last. Oretha Castle Haley and other students before us held demonstrations out at SUNO. After us, Earl Picard and another generation of students led major demonstrations. SUNO was full of older than average, working class students. Adults. People who had jobs and chidren to raise. People whom you could not treat like naïve teenagers. That is the background and the context within which my personal experiences were subsumed.

The SUNO struggle was who I was, everything else was secondary. Everything.

We modeled our movement on what we understood of the liberation struggles then coming to fruition in Africa. I was particularly impressed with Amilcar Cabral and the PAIGC in Cape Verde/Guinea Bissau. One of Cabral’s clear directives, which I took as a personal maxim, was: “mask no difficulties, tell no lies, claim no easy victories!

For two months April and May of 1969, SUNO was a liberated zone. We ran a newspaper giving our analysis of things. Held daily meetings with students in the science lecture hall. Allowed any and everyone to speak at the meetings. And in general out-organized our oppositions.

One thing we did that was important. We delegated leadership positions far and wide, and not simply to those in our inner circle.

Once someone was put in charge, they were in charge and made all decisions. One of the brothers who ran the school paper was gay. My position was as long as the paper was coming out on time and was well done nobody had anything to say about who should or should not be running the paper. Period.

Forty years later I still run into comrades and fellow students from the SUNO Spring of ’69. I don’t know most of them personally but they know who I am and I embrace them, literally, embrace them in celebration for who they are and for their participation when it counted. For many, many people SUNO was a highlight of their life experiences.

Today, when I have these chance encounters, I am always proud. I am forever grateful to have had the opportunity to be part of the SUNO struggle. The majority of the lives that were touched were not the uppity-ups, the petit-bourgeoisie in training to become functionaries in the state machinery. No. I’m talking about ordinary street people. We speak with pride and love when we briefly reminisce about the SUNO days.

In the Spring of ’69, I had just turned twenty-two. I and most of my comrades were physically fit, mentally quick, and on revolutionary fire. Being the grandson of two preachers, some would say I had inherited the gift of gab, but in that department I was no different that local leaders in black communities and among black students all across America. We all could rap.

Of course, my commitment to writing and theatre was a big plus. I had the ability to utter witty phrases that captured the essence of what we wanted and often mercilessly ridiculed our opponents.

I had a poem I frequently performed during that period. The poem was called “Knuckle-headed Niggers.” I would run down a list of deficiencies evidenced by knuckle-heads. People would be falling out laughing. I ended the poem with my fist shot high in the air in a black power salute and urged my audience to do the same. And then, while bouncing my fist against my own head, I would say, “now tap your fist against your head—how does your head sound to you!”

We were determined to be true revolutionaries and not simple-ass, knuckle-heads thinking that revolution was a party. No, people were putting their lives on the line, some of us, such as my grandfather and Jean Kelly’s mother had actually died during this time period. We weren’t just college students playing pranks.

We knew: to play at revolution was to be put down. We were serious, the times were serious. One way or another, change was going to happen. Our goal was to the best of our abilities to direct the changes in our society, and where we lacked the ability to direct, we certainly had the ability to influence.

Our flag was flying, our people were on the move, change was being made. At SUNO, in New Orleans, and all across America, these were difficult and dangerous times and simultaneously this was a beautiful era of revolutionary optimism and opportunity. Nineteen sixty-nine, a great time to be alive.

—kalamu ya salaam