30 September 2017

Joseph Rymer, Mabel Bryan and Alex Hazelwood, who were helped by Barnardo’s . Photograph: Courtesy of Barnardo’s

A hidden store of remarkable personal testimonies, told by a selection of black children and teenagers given shelter by the Barnardo’s organisation up to 120 years ago, has been shared with the Observer this weekend, along with a series of original admission photographs.

These unseen stories, released by the charity to mark the start of Black History Month, stand out not just because of their moving content, but because of the valuable glimpses they offer of some forgotten corners of history.

One “Dr Barnado’s boy”, as they were called, recalls seeing the head of General Gordon carried aloft by Arab soldiers during his childhood in Sudan. The 16-year-old, Jaesell Macalonzie, had watched his family massacred by Mahdi troops at the siege of Khartoum. Although wounded, he survived to be sold as a slave, and then freed, before sailing on to England.

Other children talked of dramatic rescues at sea, or of desperate times in Britain, living on the edge of survival in brothels or street gangs.

These official “admission statements” were given to staff at Barnardo’s by young people as they were offered a home. Their words represent a wave of human suffering that brought many vulnerable youths to British ports, or later set orphans running from poverty back on track, after an early life in which they had been passed about like unwanted property.

“Barnardo’s started its work in 1866, 60 years after the end of the slave trade, and it was the first national children’s charity in England to take in vulnerable black and mixed-heritage children,” said Javed Khan, chief executive of Barnardo’s. “Our goal then was never to turn away a child that needed us, and that remains true today.”

The work of Thomas Barnardo began in London’s impoverished East End, where he founded a “ragged school” to provide basic education for neighbourhood children. One evening a boy called Jim Jarvis showed him destitute children sleeping on roofs and in gutters nearby. Barnardo then set out to offer a roof to as many of them as possible.

In 1870, the charity opened a home for boys in Stepney Causeway. Its door bore the sign “No Destitute Child Ever Refused Admission”, following the death of an 11-year-old boy called John Somers, just two days after he had been turned away because the shelter was full. A “Girls’ Village Home” was also founded in Barkingside.

Barnardo’s stopped running homes for orphans more than 30 years ago, but it still supports the lives of hundreds of thousands of young carers, care leavers, foster carers and adoptive parents across Britain with training and parenting classes.

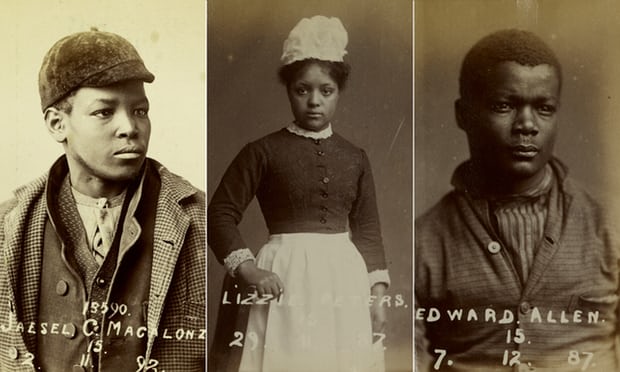

Jaesell Macalonzie, Elizabeth Peters and Edward Allen. Photograph: Courtesy of Barnardo’s

EDWARD ALLEN

Born in the West Indies and admitted to Barnardo’s in December 1887, aged 15.

Edward ran away from home and joined a ship which foundered near the Western Islands, now known as the Azores. The ship’s crew were saved by a passing steamer, which took them to São Miguel, the largest island in the archipelago.

The British Consul provided board and lodging there and, after four months, was able to get Edward on a ship to London, where he became destitute and was taken in by Barnardo’s.

He returned to the West Indies the following year.

JAESELL MACALONZIE

Born in Somalia and admitted in November 1892.

Jaesell was taken to the Liverpool Barnardo’s home after he was found in the streets with a shoeshine box, but no idea what to do with it.

Once he was in the home, his story spilled out: “My father was a soldier under General Gordon. At the fall of Khartoum, the Mahdi’s troops killed my father, mother, sister and younger brother. I was stabbed in the neck and left for dead. A Sudanese soldier disguised me as an Arab and removed me to Dhurman. I remained there for seven months, when I was seized by Arabs and sold as a slave. After having been so disposed of two or three times, I eventually reached Alexandria, whereupon my owner gave me my liberty.”

ELIZABETH PETERS

Born in 1872 and admitted to Barnardo’s aged nine.

Elizabeth grew up in Liverpool, one of four sisters, and was employed for a short time as a child dancer.

The family moved to London, where their father abandoned them to take up a position as cook on a ship bound for Sydney. He left no money for his children and, soon after he left, the youngest sister died. Despite the mother having a job as a cleaner, the family ended up in a workhouse, although the children still went to school.

When Elizabeth and her sisters came to Barnardo’s, she was described as “remarkably intelligent”. The report added: “She reads fluently and seems eager to learn.”

She went into domestic service in 1887.

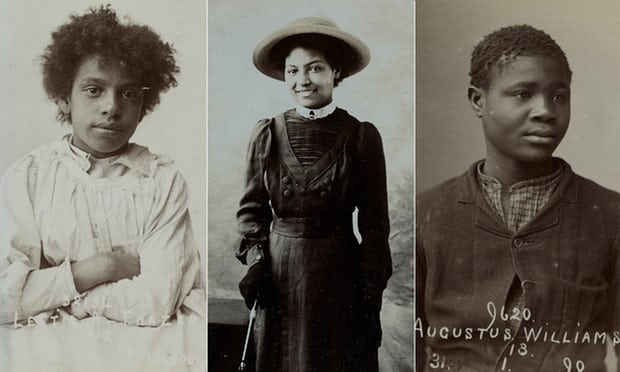

Letitia Frazer, Marie Roberts and Augustus Williams. Photograph: Courtesy of Barnardo’s

MARIE ROBERTS

Born in 1895 in Stamford Hill, north-east London.

Her mother had a relationship with a lodger, who deserted her soon after the birth of Marie.

When Marie was 10, a Barnardo’s application was made by a relative to take her in, as her mother was in Tottenham hospital, where doctors described her as suffering from “sheer starvation”. When the Barnardo’s agreement was taken to the mother, she was too exhausted to sign it, and it had to be approved by her half-sister. Her mother died shortly after.

Marie went into domestic service in 1914.

LETITIA FRAZER

Born in 1894 in Cardiff, she was admitted in March 1904, aged 10.

An application was made on Letitia’s behalf as she was found to be in “circumstances of extreme moral danger”.

Her mother was destitute so, aged three, Letitia was placed for adoption with a couple who were later convicted of keeping a disorderly house. Letitia was returned to her mother, who was “living an immoral life by consorting with other men”. More concerning was the discovery that a young black girl who had been living with Letitia was keeping a brothel. Letitia ran errands for her and sometimes visited the brothel.

AUGUSTUS WILLIAMS

Born in Portland, Jamaica, in 1871, he was admitted in January 1890.

Augustus lived with his mother who worked as a dressmaker following the death of his father in Kingston.

In August 1889 she too died of fever and Augustus made his way from St Lucia to London, arriving in December 1889. Barnardo’s sheltered the destitute youth.

In a reply to a letter from the charity, Horatio Vaz, clerk to Kingston’s circuit court with whom the boy had once lived, wrote: “I am glad to say he is well known to me. I found him to be a good and honest boy. I suppose, wishing to see a little of the world, he left his home.”

Augustus returned to sea in late 1891, but his fate is unknown.