Digging and Bluing

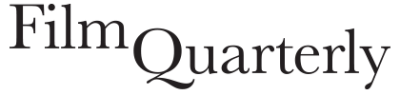

with Billy Woodberry

by Josslyn Luckett

from Film Quarterly Summer 2017,

Volume 70, Number 4

We hear a familiar sound,

Jazz, scratching, digging, bluing, swinging jazz,

And we listen

And we feel

And live.

–Bob Kaufman1

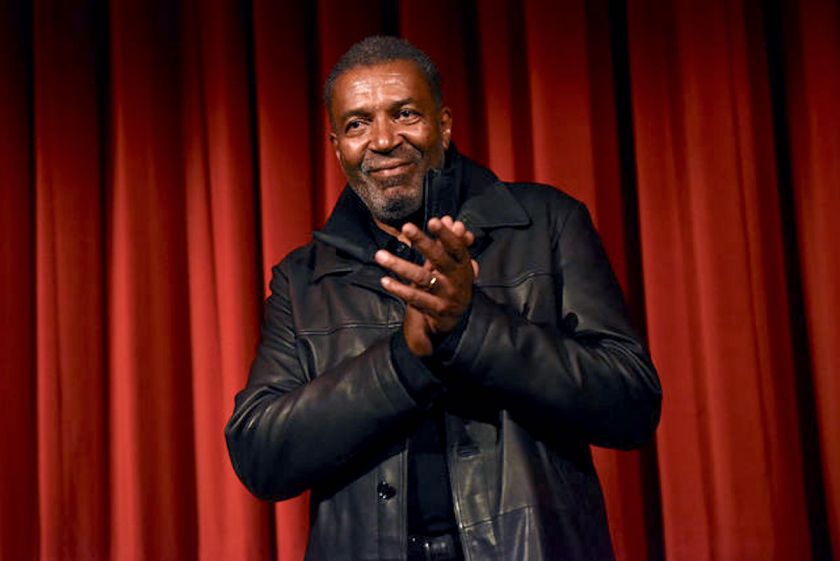

In his documentary feature And When I Die, I Won’t Stay Dead (2015), Texas-born, UCLA-trained filmmaker Billy Woodberry does for the poet Bob Kaufman precisely the kind of excavation work Alice Walker must have had in mind when she charged: “A people do not throw their geniuses away. And if they are thrown away, it is our duty as artists and witnesses for the future to collect them again…if necessary, bone by bone.”2

As early as 1972, black feminist literary critic Barbara Christian attempted to run interference on the forgetting or disposal of Kaufman. In an essay for Black World, “Whatever Happened to Bob Kaufman?” she alerted readers that Kaufman was “still alive” and “need not be praised after his body is gone and only his poetry remains.”3 By 1996, marking the posthumous release of Kaufman’s Cranial Guitar (along with the debut of Paul Beatty’s White Boy Shuffle, whose poet protagonist bears the surname Kaufman), Greg Tate lamented: “Bob Kaufman been dead (since 1986) and is unlikely to turn up on any Dead Poet Society’s reading list this side of the Nuyorican Poet’s Café. While he was here, though, he damn near invented the Beat poetry scene on the West Coast. Since he’s rarely credited for this or for having even lived, you know he must have been a black man.”4 Though solitude, suicide, and death march through Kaufman’s work, like the dirge of so many street funerals in his native New Orleans, Woodberry and his film now take their place in the dedicated second line of black writers and scholars, and the multitude of artists and witnesses who refuse to let Kaufman “stay dead.”

And When I Die, I Won’t Stay Dead had its world premiere in the fall of 2015 at the Doclisboa Festival, where it won the RTP Award for “Best Investigation Documentary.” This is the second film by Woodberry to win festival prizes in Europe; the first, his narrative feature Bless Their Little Hearts (1983), won the Berlin Film Festival’s Otto Dibelius Film award at the time of its debut. With three decades between the two films, one could equally wonder, “Whatever Happened to Billy Woodberry?” In fact, on the winter night when the Scribe Video Center and the Philadelphia Film Society hosted Woodberry for a screening of the two features—preceded by Woodberry’s latest short, a poetic bow to Ousmane Sembène, Marseille après la guerre (Marseille After the War, 2016)—I overheard two hipster millennials wondering as much. They had come because they were eager to see “that film that was sampled” (did they really say sampled?) in Thom Andersen’s Los Angeles Plays Itself (2003).

Woodberry’s Bless Their Little Hearts, Charles Burnett’s Killer of Sheep (1977), and Haile Gerima’s Bush Mama (1975) dominate the final section of Andersen’s video essay on the history of Los Angeles as rescued in films. Jacqueline Stewart, co-curator of the UCLA Film and Television Archive’s exhibition “L.A. Rebellion: Creating a New Black Cinema” (2011), suggests that Andersen’s use of these “landmark L.A. Rebellion features” offers “long overdue, materially grounded correctives to the distortions and mythologies presented in so many white-authored cinematic representations of the city, particularly those generated by Hollywood.”5 Stewart and her partners, Allyson Field and Jan-Christopher Horak, along with filmmakers like Andersen and earlier waves of cultural critics such as Toni Cade Bambara, Ntongela Masilela, and Clyde Taylor, insist that reel/real black Los Angeles will never be dead as long as the early works by this group of UCLA-trained filmmakers remain available. And it is important to note that Woodberry’s recent projects are just two of many new projects by “rebellion” filmmakers: Barbara McCullough, Julie Dash, and Zeinabu irene Davis all have recently completed projects making the festival rounds in the last two years.6

The unfolding of Billy Woodberry’s career—both his own new work and the recent critical revaluations of his classic work, such as the naming of Bless Their Little Hearts to the National Film Registry in 2013—makes words like “rebellion” or “revival” only marginally useful. Any research into the full range of his film work, including his multiple roles as film actor, film narrator, video installation artist, and film history and production professor at California Institute of the Arts (CalArts) since 1989, reveals a Woodberry who might be more properly termed an underground “renaissance” man than a rebel.7

In the words of Cornel West, Woodberry might also be thought of as “a bluesman in the life of the mind, a jazzman in the world of cinematic ideas.”8From Archie Shepp and Buddy Guy on the soundtrack of Bless Their Little Hearts to Billie Holiday, Irene Aebi, and Steve Lacy featured in And When I Dieto, most recently, Josephine Baker and Moussu T e lei Jovents as the sonic landscape for Marseille après la guerre, jazz and blues, yes, are everywhere in Woodberry. But they are not the exclusive musical terrain: spirituals, folk music, art songs, and all manner of avant-garde music live there, too. The life of the Afro-diasporic literary mind lives in his films as well, starting with The Pocketbook, his 1980 short film adaptation of Langston Hughes’s story “Thank you, Ma’am,” and continuing throughout Kaufman’s wide-ranging canon. The latest example is the contemplative collage of Marseille, which he uses to imagine the time, space, and struggle that informed Sembène’s first novel, Le docker noir (Black Docker, 1956). Toni Cade Bambara did say back in 1993 that one of the chief tasks of the “Black insurgent” filmmakers from UCLA would be the recovery of “our own suppressed bodies of literature, lore and history,” and Woodberry has remained committed to telling this history, imagined and lived, through a subaltern lens.9

This article is based on my expansive conversation with Woodberry, held in the middle of his two-day trip to Philadelphia and bookended by the screenings at the Philadelphia Film Society and his masterclass, “Creative Approaches to Documentary Filmmaking,” at the Scribe Video Center. He seemed at times more interested in discussing the history of African American labor organizing than his two most recent films (though to be fair, the National Maritime Union archives were central to the research of both). He shared detailed reflections of his film school days, including mention of one of the underexplored figures of the UCLA group, Elyseo Taylor, the sole black professor at the film school, recruited by former Theater Arts chair Colin Young to help establish the Ethno-Communications Program. This affirmative action initiative brought in not only key “rebellion” members but also a wider group of Asian American, Chicana/o, and Native American students that, as Renee Tajima-Pena reminds us, “changed the color of independent filmmaking.”10 Whether discussing his time as a student at UCLA or as faculty at CalArts, it’s clear that the relationships he cultivated at both institutions have had a tremendous impact on his creative practices as well as his deep affection for the Los Angeles that plays itself throughout so much of their work. I offer my own deep thanks to Hye-Jung Park and Louis Massiah at Scribe for generously creating the context for such a rich exchange to take place.

Josslyn Luckett: The opportunity to see all three of your films, Bless Their Little Hearts, And When I Die, I Won’t Stay Dead, and Marseille après la guerre, back to back last night made me think a lot about the three subjects of these films—that is, along with Bob Kaufman and Ousmane Sembène, I include Charlie Banks, your fictional protagonist in Bless. Talk to me about those three men, because they share a lot. But Charlie doesn’t have a poem or a guitar or a camera. And that’s in some ways what’s most devastating.

Billy Woodberry: Yeah. (Charlie) has…he’s not a writer or artist or whatever, but he has an inner life and a spiritual idea. He has his way of being in the world. He’s expressive and articulate in his own way. I think he has that. Also, that actor (Nate Hardman), his talent, his artistry is what gives the illusion. It gives him meaning and the sense of this character. And her—and the children—his playing with her, his acting with her and with them…he gives Charlie meaning.

Luckett: I want to continue with Bless Their Little Hearts for a bit. Can you tell me about that scene in the kitchen between husband and wife, played by Hardman and Kaycee Moore? I wondered how much you let them loose.

Woodberry: Charles Burnett [the screenwriter] wrote a whole page of description about that confrontation, that encounter with them, but he just wrote the description. Where they are, what she knows, what he knows, what he might attempt to do to explain, and what she will perhaps…how she will respond. But he didn’t write the dialogue. He just wrote that. And with that, they created the dialogue, they created the scene.

Luckett: It’s really something to watch that scene right now after having just revisited Fences through Denzel Washington’s recent film adaptation [2016] of August Wilson’s play. There’s a lot of resonance. The play was first staged in 1983, the same year as your Bless Their Little Hearts.

Woodberry: With language and with action, he was thinking of similar things.

Luckett: Changing gears, let’s talk about two of your new subjects, Bob Kaufman and Ousmane Sembène. They inhabit very different places, but they are surprisingly similar figures.

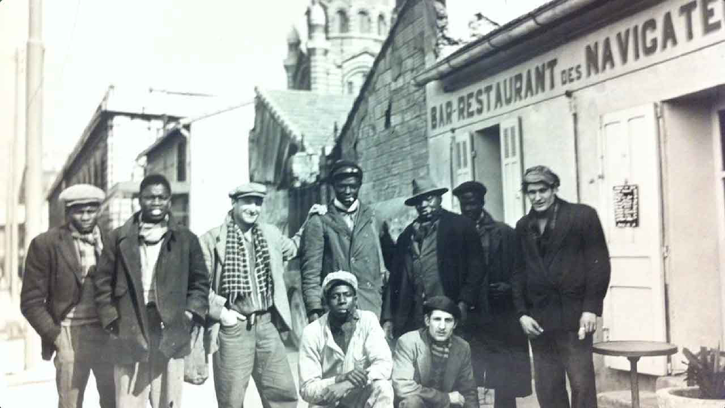

Woodberry: Maybe because they were artists…who when they were younger were involved in labor and organizing and politics. Had to do with ports and waterfront, with travel. And they were sort of militants involved in trade unions, communist party politics. And also, maybe because they were self-educated, partly, or they found the possibility of studying in nontraditional contexts. They didn’t go to university.11 Kaufman said he tried to go to the New School a couple of years, in 1948 or something. But it was different…the National Maritime Union (NMU), apparently, they had educational programs…A man named Leo Huberman who with Paul Sweezy created Monthly Review Press…was a teacher in their union. Apparently, their program was so good, you have to find out for sure, Columbia Teachers College used to send people to observe them.12 But also, you know, because sailors are at sea a lot, they have an historical tradition of reading [and] literacy. And Kaufman had the double benefit that his mother was a reader and was a trained teacher. When she could no longer teach in schools, she taught her children, so all of them read and write.

Luckett: Though we know from your film, and from his poetry, that Kaufman is extremely well read and was, as you just said, the son of an educator, he is at the same time consistently labeled a “street poet.” How do you explain that?

Woodberry: In some ways, it’s true. As Jack Hirschman says, Kaufman was a man of the/ in the world and he was a man of the street. But people think that that only means people who hang in the street ’cause they don’t have anything else to do. It can mean other things. Maybe he’s pleased with that. To master the street and the encounters and the dimensions of the thing could mean something other than being a derelict or hustler or whatever. It can mean more than that. You could read what Baudelaire says about the street and about the way one encounters life in the city and all of the possibilities of what happens in the street. Even now when they talk about the “Arab street,” what it means is: you in the corridors of power, you may have one understanding, but the people on the ground, the people of the street have a different understanding and you should be concerned about how it will play. And that’s true here. I mean we just had this recent election…And then on January 21st, the day after the inauguration, and then the following weekend when they proposed the ban, they saw people take to the street. The street is a place where people manifest their protest, their agreement, approval or disapproval.

Luckett: I’m flashing back now, all the way back to The Pocketbook which shows a different situation of the street.13 There is care and rescue in the street in that film.

Woodberry: Kamau Daáood says the street is a place of hard wisdom…lessons you won’t learn anywhere else.14 So, that’s the thing…the kid [is] hanging out in the street; of course, your parents don’t want you hanging in the street because you can pick up bad habits, bad notions, bad ways of being and you can get into things. And he discovered that…the people who are in the street, it’s their job, it’s what they do. So, in a way he learns that lesson. She’s a lady who’s on the street after the job. She [Mrs. Luella Bates Washington Jones, the story’s protagonist] gives you a different lesson than you thought you would get. She gives you a different complex challenge. And Langston Hughes knows stuff like that. He (the kid) wants to be in the street, and she’s telling him, you need to understand. You wanna take something from me? You need to know what my having that entails. It’s a cost involved.

Luckett: It’s wonderful to see that actress again, Simi Nelson, who played a similar “lesson giving” character in Haile Gerima’s Bush Mama, a very different character than the one she plays in Alile Sharon Larkin’s Your Children Come Back to You (1979). In Larkin’s film, the adult is “schooled” by a child, played by Angela Burnett—who also plays the oldest child in Bless Their Little Hearts. This also speaks to the beautiful cast of working actors you all had.

Woodberry: The thing was [that] we shared them…the relationships and the understanding and generosity of those people…they were helping to create whatever we thought we were doing. They understood the demands of it. And they were sacrificing for it, because they weren’t paid to do that. They were understanding and creative and supportive, so the main thing was: don’t screw up the relationship because it doesn’t belong to you. It belongs to the next one. So, it was like a company.

Luckett: I’d like to get back to your Bob Kaufman film. Can you say more about your impulse to begin making And When I Die, I Won’t Stay Deadwhen you did?

Woodberry: I learned about him in the ’70s, but I didn’t really know or follow poetry much. But a friend I had at the time did. It was always told to me how unique he was, how significant he was, how interesting he was, this kind of thing. I didn’t take a real interest in him, until I was in City Lights bookstore [in San Francisco] in 1986 in maybe March, and he had died in January. There was a special issue of Poetry Flash, which is published in Berkeley. It was the cover article, and it was interesting and gave a lot more information about his background, about his origin and the different mythologies that surrounded him, also the appreciation of the people of the poetry world of North Beach who knew and admired his work. So, I thought at the time—it was only a couple of years after finishing Bless Their Little Hearts—oh I would like to make a short movie about him, make a tribute to him…that could stimulate people to be interested. But then I couldn’t figure out how to do it. As I learned, as I tried to find more information, it seemed that his life was sort of tragic, and I didn’t know how to confront that, so I put it away.

Then, about [the year] 2000, my friend brought it up again, and I thought, okay, I should look at it and see if there’s something there. I was working on another project, a video project about the building of the Walt Disney Concert Hall. It was a commission from my friend Allan Sekula. He invited me and four other photographers to collaborate with him. So, I started working with this small format video that had become digital video. I spent three and a half, four years shooting the building of that concert hall.

Then I started to think about Kaufman. That’s when I seriously started to research it, to travel to meet people, to try to discover what was there, what I could accumulate toward making a film about him. It was said that there was an archive of his work in the special collections at the Sorbonne. So, I went to the Sorbonne, and I saw that. At the time, I was sort of traveling again and I was enjoying that and I was sort of mobilizing myself to be active again. And then I went to San Francisco quite a number of times before we actually went back to do the shooting. And I started to find the associates and people connected to him. They helped me a lot, directing me to the research. Then about 2006 or so…I started to shoot seriously with my friend Pierre Desir.

Luckett: Desir was also from the UCLA group?

Woodberry: Yeah. So, we started to travel a lot and find people and try to collect the interviews…We tried to have people who knew him, really knew him. And then we had another group, the people who learned of him through their research and scholarship and who helped to revive and to promote an interest in his work. So, that was sort of how it went. After we had all the material, I had to start to work on the editing, to shape and figure out what it was.

Luckett: Bob Kaufman may have been the greatest perpetrator of his own myths of origin, including the tale that he was the son of a Martiniquan voodoo-practicing mother and Orthodox Jewish father. Scholars and poets like Harryette Mullen and Maria Damon help demystify some of these “colorful but fictitious” claims by clarifying that he was from a middle-class, African American, Catholic family in New Orleans, and that the German Jewish relative was at least two generations back on his father’s side.15

It is one thing to hear this or read these biographical bits, but when your film physically travels to New Orleans to meet this family, his sisters, his niece, something really powerful happens that vintage footage of Kaufman seen earlier in your film (mostly photographed in the Bay Area among his white poet cohort) cannot accomplish. The New Orleans section, as well as the surprising interview with his Puerto Rican first wife, Ida Berrocal Torres, and the archival images of his black labor organizing comrades like Ferdinand Smith, ground Kaufman in a pre-Beat, black and brown past.

Woodberry: I think there is a counter view to the idea that the Bohemia of North Beach was just a “white” thing. The presence of many black people in the footage in the café and the “Tour of the Bourgeois Wasteland” shows that they were there in sizable numbers. This “race-mixing” was what was objected to by the police and others in authority. And in fact, Kaufman had a number of close black friends including a poet named Conyers that I was never able to interview. A number of them had roots in New Orleans and his relationship with them was quite apart and special. Mona Lisa Saloy, the poet from New Orleans who appears in the movie, she told me about this.

Another thing missing from the film is his closeness to his older brother George and his family. They lived in Oakland and George, who was the closest to him of all his family members, always knew where Kaufman was and how he was doing. When his sisters visited from New Orleans and other places, they knew how to arrange meeting him through George.

Luckett: Tell me more about when you first discovered his family in New Orleans and also his first wife, Ida.

Woodberry: I knew about the family, I knew about his sister. I knew about his family through Mona Lisa Saloy. She knew his family. I had a friend from high school who worked as an administrator at Xavier, and he knew the sister really well. So, he helped to connect. And through him I got her phone number, and I talked to her. And for some reason they were always hesitant to speak. They’re very dignified people and they don’t like…they didn’t like the version of his biography that was around. But eventually she agreed to talk to me. And…she invited her youngest sister and her niece to come… [But] she didn’t want to be on camera, so I said okay, so we just filmed a photo on her wall, until the niece convinced her.

Luckett: The niece who is in the film?

Woodberry: Kelly, yes. Wonderful people, wonderful. When I arrived, she gave me the photograph of the four, the two sisters and two brothers. She was going to give me probably a much better photograph of her parents and that kind of thing. But, unfortunately what happened was [that]…she lost all of her things during Katrina. So, it must have been 2005. I think we were there some months before [Katrina].

Luckett: It is amazing that you got to them before that, or you might not have had anything.

Woodberry: Also, Mona Lisa Saloy was writing her dissertation, which was about Kaufman, and she lost all of her research. But because she had given me copies of a lot of things, I could give them back to her.

As it happened, we were in Minnesota with Maria Damon, who was one of the first people to do serious scholarship about him and his biography. She had found a copy of the newspaper The Pilot, which was the newspaper of the National Maritime Union. And she was reading an article about a strike in 1947 that (Kaufman) was the rank and file leader of … and she mentioned his first wife, Ida Berrocal. I then went back, because the internet makes this possible, and I put the two of them in the search together, and what came up unfortunately was his daughter’s obituary: Antoinette Kaufman Nagle. That’s how they were linked.

I then said, oh this is horrible, because Mona Lisa Saloy and Maria were always asking me if I ever found Antoinette, if I knew where she lived. Mona Lisa thought she lived in the Bronx…I credit them privately and publicly because it was their question [that] made me sensitive to that issue. I looked…[for] almost two years, then it was through Antoinette’s husband, Michael Nagle, I found this connection with Ida. I called her up at her office. She was still the head of the Local 3 at the wholesale and retail worker’s union. I got her on the phone, and she said, “Okay, I’m involved in negotiating a contract, you call me back in a month and I will talk to you.” She told me that and it took me three or four years to talk to her, and Michael Nagle is the person who convinced her, because they talked every day. He said, “I know you don’t like to talk about Robert.” She said, “Michael, I’m old enough to realize that it takes two to have a conflict.” And it took two years, and she was as formidable as you see. She died last year at 92.

Luckett: I wanted to ask you about these discoveries, because it seems to me that they shape how you decided to pace and unpack the film. As a viewer, I certainly experience it that way: that this is what you think you know, this is what you might know, and then these are the things you have no idea about.

Woodberry: I think that’s perceptive, because in part the structure is derived by the process of discovery. What I mean by that is when I decide to talk about his origin family it is late in the film. And when I decide to talk about his history as a militant in the trade union movement, it’s like a flashback…but it’s the process of discovery. When you meet him, you learn about him as this figure in North Beach. We go through that first—we go through that until it goes someplace else, when he goes to New York and then he returns. And then you have the people, some of whom knew him earlier, meet him again. It’s the years from 1963 to the early ’70s when he starts to be active again, participate in the poetry world. And at a certain point I thought…you still have questions: Who is this guy? Where did he come from? So, then it seemed it was possible to go back. So, that’s sort of how I came to it [the structure]…trying to retain the process, to honor the process, but to see if you in fact can retain the interest of the audience. Seemed right, and it seemed to work.

Luckett: When I saw Grace Lee’s American Revolutionary: The Evolution of Grace Lee Boggs [2013], I was struck by the moment when Jimmy and Grace Boggs appeared on the public television program, With Ossie and Ruby! [PBS, 1981–82, 1985]. For me, to see Ossie Davis and Ruby Dee’s involvement with Kaufman’s poetry in your film was similarly striking.

Woodberry: They had progressive politics and broad interests. They took the mission of public television seriously. They thought it could educate, inspire, and you can recover a kind of political culture that may not be so obvious.

Luckett: I am curious about when and how the Sembène/Marseille project came to you? Was it in the midst of working on the Kaufman piece?

Woodberry: A former student was helping me. I asked him to go to that collection, and he got a lot of things that he thought would be helpful. But then, because he knew me, he found this [other] group of photographs and he thought, Billy will find this interesting.

Luckett: Which archive was this?

Woodberry: He found them in the Tamiment Library and Labor Archives at NYU. There’s a collection of photographs from the NMU, National Maritime Union, there. So, after we finished all the editing on Kaufman, I said to the editor [Luís Nunes] that we maybe could do something with them, we could make a little film. And we talked about Sembène and the idea that Sembène was there. He didn’t know about Sembène, so he spent the night learning about Sembène, learning about his life, his movies. Then the next day, we sat down…And I had an idea, so we made a version, we made the structure. He spent the night again working, decoupage, exploring all the possibilities inside. And then we met again, devising the sound. We knew the music at the end, we knew we could use Josephine Baker, because she was part of the imaginary of the people. So, then I thought okay, I knew the story, I knew what I wanted to say. Then they insist that I write and record a narration for them, explaining it. And I don’t like that…so we made two versions. We made one without and one with. Most people prefer, seemingly, the one with, where I tell the story of how I, why I did that, what I was thinking.

Luckett: The narration, or lack of, was interesting in the Kaufman film, too. Tell me about your choices there.

Woodberry: There’s very little voice-over. The thing is, okay, narration has come back to nonfiction film and a lot of different kinds of filmmaking. I’m not a great writer of narration, and I recognize that. I don’t like narration that is overwhelming: if it’s not telling you what you’re seeing, it’s telling you so much that you’re not seeing. Not everybody is as great at it as some. Chris Marker is great. Raoul Peck is very good, and others. So, I know my limitations. But I wanted to have a creative way of offering narration. And I like end titles. And I have some narration: I had Maria Damon doing it, other people were doing it, and I ended up doing it myself. Some of the technicians and people thought it was a better idea. So, I did that. And the poetry, some of it I read, they convinced me that’s a good idea and the best idea, so I read. But that’s how we did that…and it was very fast. Two days.

Luckett: Didn’t Sembène actually come to the UCLA campus in 1970?

Woodberry: [Elyseo] Taylor was the guy who brought the state department tour of African filmmakers. He brought Sembène.

Luckett: Did you get to see Sembène then?

Woodberry: I’m not sure if I saw Sembène at UCLA. I saw Sembène at Howard University when Haile [Gerima] was teaching. And I saw Sembène at screenings in different cities.

Luckett: You arrive at UCLA in…?

Woodberry: Like ’73, ’74.

Luckett: Okay, so you did overlap with Professor Elyseo Taylor, the sole black member of the faculty at UCLA’s film school in the early “L.A. Rebellion” days. He is such an important “hidden figure” in the department, instrumental, through the Ethno-Communications Program for bringing in not only key “Black insurgents,” as Toni Cade Bambara would refer to your group, but also Chicana/o, Asian American, and Native American filmmakers to the department in significant numbers for the first time.

Woodberry: That was enriching, because it gave us a wider view of the world, a greater sense of possibilities, a greater sense of the dimensions of the problems to learn about, the social realities and structure and you know the class issues. It challenged us…it was possible to grasp the idea that there’s social conflicts beyond the ones you know, beyond even the black and white binary, right? You learn, no, it’s more complicated than that…And we used to argue and struggle about that.

I remember during the Second Gulf War, in 2003, when they were proposing interning people, it was the Japanese American community that were the first ones in the streets. And I saw Bob Nakamura and (he) said, “You know they’ve been yelling at us for twenty years, thirty years, ‘Why do you keep talking about the camps? Why’re you talking about the camps?’”16 And they were the first people to make a public protest of it. And I think that was healthy and good. And those relations with people among the different groups carried beyond school, because they supported each other in creating a lot of the consortiums and media groups within public television and other things.

Luckett: This must be a question you get asked all the time. How do you feel about “the L.A. Rebellion” as an expression and as a category?

Woodberry: It’s a concept that originated, like a lot of times the names for these things originate, with scholars, critics, others outside of it.17 And you can kind of accept and appreciate it, because it’s not mine or our concept, but it’s a concept that somehow caught on and it seems to work for people beyond those [originally] involved.

[Ntongela] Masilela and others always link it to the uprising in Watts and the cultural and political and social ferment and the role of that in bringing to attention the demands of black people and others for access to the institutions and resources that are afforded to taxpayers and citizens—which was not acknowledged. So, the people of Watts rebelled. The people of Los Angeles in many aspects rebelled. Or they created the atmosphere and the possibilities. And we benefited.

And maybe it was a part of the consciousness of the group prior to my coming, that one should make work that is somehow connected to people beyond the university, into the larger what they call “community,” right? And even with all the internal differences and ideological positions and postures, they created a kind of ethos where that was a value that one was at least advised to consider. And then not only did they assert that, they provided support and example to help you do that. They sometimes tutored you outside of their formal responsibilities, if they were your T.A., whatever. Haile [Gerima], in fact, used to work in what was called the tech office, and Haile’s the guy who taught me how to load a 16mm camera. And he did it because it’s something you need to know.

So, maybe it sounds sentimental but this is what happened, this is what they did. And they didn’t tell you exactly how to make the film, they didn’t tell you, “You have to make the film like me.” They told you that you needed to make a film. “Don’t talk a film, show a film.” Then they offered support and encouragement and example…so, that was what I saw in that.

Luckett: The city itself and its other artists play such an important part too in the work of the Rebellion filmmakers. I think of Barbara McCullough’s work with visual artist David Hammonds, musician Horace Tapscott, and others.

Woodberry: Barbara [McCullough] was special because she brought her interests and her connections to those in the fine arts, people who later became famous. A lot of them brought different things. Ben [Caldwell] brings something different. Charlie [Burnett] knows the city, has a deep and special connection and memory of it, and he shares that. A lot of us came from outside…we came to learn and try to show something about it and be in a place. It was the people of Los Angeles. It’s their university, and they were the ones who made the fight and proved themselves in it over and over…since Ralph Bunche. So, when police were bothering us at night when we were editing, looking at us like, what are we doing here? I look at it like we had a perfect reason to be there, because maybe Ralph Bunche, Kenny Washington, Jackie Robinson, Woody Strode, and all those people paid our ticket.

Luckett: It’s a serious legacy. The opportunity to re-experience the cinematic parts of this legacy, with these recent restorations of the L.A. Rebellion films—I’m thinking especially of this new DVD collection of the shorts made available by the UCLA Film and Television Archive—is really astounding.18

Woodberry: The other thing about Los Angeles, like when Alile Sharon Larkin, in A Different Image [1982], films different signs and different things on places like Pico Boulevard, the places they filmed…those places no longer exist. So, it’s an historical record of that place. And as people have become at different times more fascinated with Los Angeles and its landscape and all these things, you see the worth of it.

Luckett: It is a visual history.

Woodberry: And Thom Andersen was one of the first to recognize that and note that and want people to know and be curious about these films.

Luckett: Speaking of Andersen, what has it meant for you to be part of the CalArts film faculty since 1989? We’ve talked a lot about UCLA, yet it seems from your collaborations with people like Thom Andersen, James Benning, and Allan Sekula that your time at CalArts has also been tremendously fruitful.

Woodberry: CalArts has been really important for me. Meeting and working with Thom Andersen, Allan Sekula, James Benning, Hartmut Bitomsky, and other colleagues has been tremendously beneficial for my life and work. The challenge of teaching the bright and creative students, to meet the demands of trying to answer their questions has been a gift.

Anderson, Bitomsky, and Sekula are great writers with vast intellectual knowledge generally, and they are radical, original thinkers about photography, cinema. I learned with them and from them, through their approach to teaching, writing, and creative approaches to making the work. The same is true of James Benning. All of them inspired my own desire to make new challenging work.

Luckett: Before we end, I wanted to see if there was anything more you wanted to reflect on about the years between your features, Bless Their Little Hearts in the mid-1980s and the release of the Kaufman documentary, And When I Die, I Won’t Stay Dead, last year. How do you think about that period?

Woodberry: I don’t know that I think about it. I sort of stopped in the ’90s, and then I started back from zero in a way, because I just started making things with a small video camera. Then I was offered an opportunity to make something longer but…it was kind of a hybrid installation. And when I had something that I could commit to, I made it. And it’s good that I could finally do that.

Luckett: It’s interesting to me that when you finally chose the new project, it was a documentary feature, not narrative fiction. Did your directing or storytelling approach change with this change of genre?

Woodberry: As you know there is a great deal of time between the two kinds of work, in my case. And I had time to think a great deal about documentary before attempting to make one. Documentary offers the opportunity to communicate in a different way than narrative fiction. It can be as rich a form as narrative/dramatic fiction, but different. Rhetorical, poetic, analytical, discursive, reflective…which in many ways is discouraged in dramatic narrative films.

So, that’s it. You know, after I stopped for a while, I was trying to get back to it in a way, but I needed something formidable. I needed something challenging and I needed to maybe suffer through it a bit. So, that’s what happened. And now I’m trying to continue. I’m trying to make the next thing and the next thing.

Notes

1. Bob Kaufman, “War Memoir: Jazz, Don’t Listen to It at Your Own Risk,” in The Ancient Rain: Poems 1956–1978 (New York: New Directions, 1981), 33, (emphasis mine).

2. Alice Walker, “Zora Neale Hurston: A Cautionary Tale and a Partisan View,” in In Search of Our Mothers’ Gardens: Womanist Prose (San Diego: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1983), 92.

3. Barbara Christian, “Whatever Happened to Bob Kaufman?” Black World 21, no. 11 (1972): 21.

4. Greg Tate, “Beats, Blood, and Rhymes,” Vibe, August 1996, 48.

5. Jacqueline Najuma Stewart, “The L.A. Rebellion Plays Itself,” in L.A. Rebellion: Creating a New Black Cinema, ed. Allyson Nadia Field, Jan-Christopher Horak, and Jacqueline Najuma Stewart (Oakland: University of California Press, 2015), 253.

6. For example, Barbara McCullough’s long-anticipated jazz documentary, Horace Tapscott: Musical Griot, premiered in February 2017 at the Pan African Film Festival. Julie Dash’s short film Standing at the Scratch Line and Zeinabu irene Davis’s documentary feature Spirits of Rebellion were both featured at the 2016 Black Star Film Festival in Philadelphia.

7. He appears as an actor in Charles Burnett’s short film, When It Rains (1995); he narrated films by two CalArts colleagues, Thom Andersen’s Red Hollywood (1996) and James Benning’s Four Corners (1998); and he was one of four artists commissioned by another CalArts colleague, Allan Sekula, to create Facing the Music, a 2005 multimedia installation on the making of Frank Gehry’s Walt Disney Concert Hall in downtown Los Angeles.

8. This is a variation of an epigram that appears in Cornel West, Brother West: Living and Loving Out Loud, A Memoir (New York: Smiley Books, 2009): “I’m a bluesman in the life of the mind, and a jazzman in the world of ideas,” (v), (emphasis mine).

9. Toni Cade Bambara, “Reading the Signs, Empowering the Eye: Daughters of the Dust and the Black Independent Cinema Movement,” in Black American Cinema, ed. Manthia Diawara (New York: Routledge, 1993), 119.

10. Renee Tajima, “Lights, Camera…Affirmative Action,” The Independent, March 1984.

11. In 1962, Sembène studied filmmaking for a year at the Gorky Studio in Moscow. See Samba Gadjigo, Ousmane Sembène: The Making of a Militant Artist(Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2010).

12. According to Huberman’s New York Times obituary: “From 1942 to 1945 he was the director of education and public relations for the National Maritime Union” and prior to that he was chair of the Department of Social Science at the New College of Columbia University. New College was an experimental “progressive” undergraduate college under the auspices of Teachers College during 1932–39. See “Leo Huberman, 65, Publisher, Dead; Monthly Review Co-Editor,” New York Times, November 10, 1968.

13. The Pocketbook is a short narrative film directed by Woodberry in 1980, based on Langston Hughes’s short story “Thank You, Ma’am.” It is one of the selected shorts featured in the UCLA Film and Television Archive’s educational three-disc box set: L.A. Rebellion: Creating a New Black Cinema—DVD Anthology 1971–2006 (2016).

14. Kamau Daáood is a Los Angeles–based poet and cofounder with Billy Higgins of the World Stage Performance Gallery in the Leimert Park neighborhood of Los Angeles. He is featured in And When I Die, I Won’t Stay Dead, reading his original poem, “Djali,” which is dedicated to Bob Kaufman. He is also the subject of the documentary Life Is a Saxophone (1985) codirected by S. Pearl Sharp and Orlando Bagwell.

15. See Maria Damon, “Introduction, Bob Kaufman: A Special Section,” Callaloo25, no. 1 (2002): 105–11, where she speaks of Kaufman’s “reinvention” as “a Beat street poet with a colorful if somewhat fictitious legacy…hybrid Orthodox Jewish and Martiniquan ‘voodoo’,” then adds that he may have had a great-grandfather, Abraham Kaufman, who was Jewish. Harryette Mullen offers a similar biographical sketch of Kaufman in a September 2007 Pen USA Festival of Poets presentation. See www.youtube.com/watch?v=EppWseVcn9A

16. Film director, educator, and cofounder of the Asian American media arts organization, Visual Communications (with Eddie Wong, Duane Kubo, and Alan Ohashi), Robert Nakamura was a graduate film student in UCLA’s Ethno-Communications Program. His student film, Manzanar (1972), a personal narrative about his childhood memories of the American concentration camp, is considered the first independent documentary to address the internment of Japanese Americans during WWII.

17. See Clyde Taylor’s preface, “Once upon a Time in the West…L.A. Rebellion,” in L.A. Rebellion: Creating a New Black Cinema, for his account of the term he created as a title for a series of black independent film screenings he curated in 1986 at the Whitney Museum of American Art (xix). See also the introduction of the same anthology, “Emancipating the Image: The L.A. Rebellion of Black Filmmakers,” where Field, Horak, and Stewart refer to the other figures: Ntongela Masilela’s, “Los Angeles School of Black Filmmakers”; Toni Cade Bambara’s, “the Black insurgents at UCLA”; and Michael T. Martin’s “L.A. Collective” (2).

18. The DVD collection (see note 13), designed as an educational tool for classroom use and individual study, has been recently made available for free to archives, libraries, and other nonprofit organizations (see http://www.cinema.ucla.edu for more information).

>via: https://filmquarterly.org/2017/06/12/digging-and-bluing-with-billy-woodberry/