A LOOK INSIDE

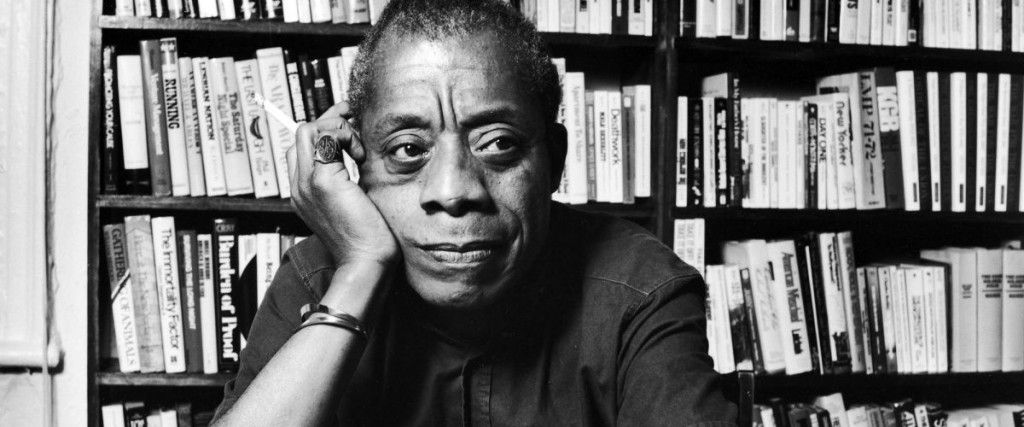

JAMES BALDWIN’S

1,884 PAGE FBI FILE

MEMOS ON “ALIASES,” SEXUALITY,

AND THE BLOOD COUNTERS

Baldwin and His “Aliases”

June 1964

Baldwin was “Jimmy” to most of his friends and to himself as well when he meditated on the various aspects of his personality. The numerous “strangers called Jimmy Baldwin,” he observed of his own diversity, included an “older brother with all the egotism and rigidity that implies,” a “self-serving little boy,” and “a man” and “a woman, too. There are lots of people there.” This secret FBI summary made the mistake of treating variations on Baldwin’s name and identity as a set of potentially criminal pseudonyms. For the Bureau, “James Baldwin,” “James Arthur Baldwin,” “Jim Baldwin,” and “Jimmy Baldwin” were “aliases” needing correlation and correction.

*

The Blood Counters and Baldwin Countersurveillance

June and July 1964

When did the Bureau lose sleep over the popularity of Baldwin’s “recent books . . . ringing up best-selling figures,” the “100,000 copies in hardcover” sold of The Fire Next Time and “the two million mark in soft covers” in sight for Another Country? It did so when a column in the Washington Post conveyed the news that Baldwin planned to publish another “book about the F.B.I. in the South.”

Hoover’s sensitivity to literary competition and challenge, always acute, had been exquisite since 1950, when Max Lowenthal’s study The Federal Bureau of Investigation, the first rigorously unauthorized history of the organization, somehow made its way to the printers without the Bureau’s knowledge. “Mr. Hoover, if I had known this book was going to be published,” swore Louis Nichols, then head of the Crime Records Division, “I’d have thrown my body between the presses and stopped it.” Nichols’s successors at Crime Records made certain that Baldwin’s FBI book—shortly given the working title of The Blood Counters—would not take them unawares.

The June memo to Cartha DeLoach identifies the book’s expected publisher, the Dial Press, and indicates in an addendum that “should the book be published, naturally it will be reviewed.” A July memo to the head of the New York field office requests a less passive form of vigilance: “Supervisor [name redacted] requested that if possible, through established sources at Dial Press, a copy of the proposed book concerning the FBI be discreetly obtained prior to publication.” Where Baldwin was concerned, after-the-fact reviews were not enough. If the country’s best-selling black author would devote his sharp tongue to the Bureau, the Bureau would be one of the first to know—and the first to try to respond in kind.

*

Hoover: “Isn’t Baldwin a Well-Known Pervert?”

July 1964

FBI headquarters urged the New York field office, also the FBI’s consulate in the capital of the US book trade, to consult the grapevine about The Blood Counters. Tactful checks should be made “among its publication sources,” the office was instructed, and agents should “remain alert to any possibility of securing galley proofs for the Bureau for review purposes.” Possible exposure of Baldwin’s book in The New Yorker made the hunt urgent: “Over the years,” wrote M.A. Jones of Crime Records, the magazine’s careful urbanity had tolerated “irresponsible and unreliable . . . references concerning the Director and the FBI.”

The FBI’s pilfering and pre-reading of Baldwin’s book was not needed: as the introduction discussed, The Blood Counters was never completed, nor was it necessarily meant to be. But its rumored appearance was enough to send Hoover to the mattresses. “Isn’t Baldwin a well known pervert?,” the director asked in the lower right margin of this July 17th memo. Three days later, M. A. Jones answered both yes and no in a bravura critical performance also discussed in the introduction. “While it is not possible to state that [Baldwin] is a pervert,” Jones concluded, “he has expressed a sympathetic viewpoint about homosexuality on several occasions, and a very definite hostility toward the revulsion of the American public regarding it.” If Baldwin had intended the prospect of The Blood Counters to unhinge the very top of the Bureau, it succeeded flawlessly.

(Hoover, he pronounced in The Devil Finds Work, qualified as “history’s most highly paid [and most utterly useless] voyeur.”) Baldwin would not have guessed, however, that an FBI reader lower down could thoughtfully distinguish between sexual identity and sexual sympathy.

__________________________________

From James Baldwin: The FBI File. Used with permission of Arcade Publishing. Copyright © 2017 by by William J. Maxwell.