A Clarion Call

by Paulette Richards

My parents wanted me to be a citizen of the world so they gave me a French name and enrolled me in a bilingual school when I was ten. They hoped that proficiency in French would open the doors of liberty, equality and fraternity for me. My language skills finally paid off in December 2016 when La Ligue des droits de l’homme (a human rights organization) invited me to speak at their December 10th conference honoring the 68th anniversary of the Universal Declaration of the Rights of Man in Guadeloupe, an overseas department of France in the eastern Caribbean. The topic of the event was police violence against African American citizens.

After the plane landed, it took me a moment to connect with the CO.RE.CA and Ligue des droits de l’homme representatives who were sponsoring my trip. Once we connected thanks to Whatsapp, they whisked me to the local public television station where I was scheduled for an interview. After a quick session with a make-up artist, I was ushered into the studio where the anchor was presenting the top stories of the day. After a few minutes it was my turn to be interviewed. I was tired so my French was more fractured than I would have liked but my appearance did help publicize the other presentations I made throughout the visit. Many people told me they had seen me on TV.

After the television interview we went to dinner. Given my dietary restrictions I always travel with my own food supply and I had been somewhat concerned about offending my hosts because in addition to being vegan, I don’t eat cane sugar or its derivatives. They were very accommodating, however, and I explained my abstinence from sugar as a response to the high rate of diabetes in my family so they arranged for a vegetarian meal and I was able to eat enough of it to do justice to their hospitality.

Finally after the dinner Hubert Jabot, president of the Ligue des droits de l’homme took me to the Creole Beach Hotel and Spa (http://www.creolebeach.com/index.php?lang=en&screen_check=done&Width=1280&Height=800) – a very luxurious establishment with beautifully landscaped grounds and a small, private beach. I didn’t get to spend much time in the hotel, however, because everyday my hosts had scheduled me for a full slate of activities.

Despite my fatigue from rising early to travel all day, I ironed my outfits and hung them up before I went to bed. Then I got up at 5am to put the finishing touches on the short paper I had drafted on the plane.

12/10/16

My hosts picked me up early Saturday morning and drove me to the University where the conference on the 68th anniversary of the Universal Declaration of the Rights of Man was scheduled. While we were waiting for the conference to start I asked Patrice Ganot, secretary of the League for help with some of the French vocabulary since I hadn’t learned technical terms like “gerrymandering” in school.

The conference organizers each made remarks and they screened some video clips of police violence against black American citizens. Then they invited me up to the panel to speak.

Since late August when I received the invitation I had been researching and marshaling my ideas. I had not been following the police shootings or the Black Lives Matter movement closely before and I had deliberately avoided watching any of the citizen journalist videos that had drawn worldwide attention to this issue because those images could easily trigger my own post traumatic stress related to racial violence I witnessed as a child. What I tried to do in my talk was place the police shootings in a historical context of systemic racism starting with the three-fifths compromise in the U.S. Constitution.

Our Founding Fathers made a Faustian bargain to keep the slaveholding states in their more perfect union by allowing them to count five slaves as three persons for purposes of apportioning seats in Congress and the Electoral College. This compromise gave the slaveholding states a numerical advantage in Congress, which enabled them to resist all proposals to abolish slavery. The compromise also added un-natural weight to the votes of electors from slaveholding states since along with the pool of eligible white male voters they represented slaves who could not vote. Five of the first seven U.S. presidents owned slaves.

My argument was that black lives still don’t have the same value as white lives due to this systemic racism. I cited quality of life indicators like the rate of infant mortality as evidence (in 2014 in Mississippi, the black infant mortality rate stood at 9.6 in 1,000 – on par with the rate in Botswana)[1].

I also cited Jill Leovy’s research for Ghettoside which suggests that while African American communities have suffered greatly from police harassment under policies like “stop and frisk” and “broken windows policing,” they may in fact be under-policed in the sense that the police have not managed to effectively investigate or prosecute violent crimes within black communities. African American men are only 6% of the U.S. population but 40% of the murder victims[2]. In some communities more than 50% of these cases remain unsolved.

Leovy notes that decades of tension between police and residents plus the move away from foot patrols has eroded residents’ trust in police officers to the point that police are unable to obtain information from witnesses that would help them solve murder cases. Furthermore she analyzes the justice system’s historic tendency to hand down lenient sentences of five years or less in cases of black on black murder while imposing harsh punishments on black men for small crimes in order feed the prison industrial complex as another indicator that in the eyes of the law black lives don’t matter.

On this note I cited the disproportionate number of black missing persons as further evidence that systemic racism has significantly devalued the lives of black citizens. African Americans make up a little less than 13% of the U.S. population but account for 34% of the reported missing persons[3]. In this way I made a small step towards bearing witness about the victims of forced disappearance that I knew as a child.

Overall, my point was that the police shootings are just a dramatic symptom of the level of violence against African Americans that has existed in the United States since the framing of our Constitution. I talked about how the skewed representation in the legislature persists due to gerrymandering which has contributed to the Republican majority in Congress and to the refusal of that majority to renew the protections of the Voting Rights Act of 1965. In response to repeated questions about whether the incidence of police shootings had increased under President Obama’s administration, I gave my opinion that the violence has always existed but remained largely unknown outside of the black community until the advent of cell phone video and social media which made it possible for citizen journalists to document such abuses and publish the evidence for a global audience.

After my presentation there was a lively question and answer session. The lecture hall had very poor acoustics and the first two questions came from the back of the room so I had a hard time understanding them. Only later did I learn that they were posed in Kréyòl. While Guadeloupe is part of France, most of the locals can speak or understand Kréyòl, a language derived from the syncretism of French with various African languages. Some League members felt it was disrespectful not to use French in this context but I appreciated the assertion of cultural pride and fortunately Julien Mérion translated for me. Here is a list of most of the questions I received:

- What is the effectiveness of the Black Lives Matter movement? How well has it served to raise consciousness?

- Is the violence against black men a surrogate for assassinating Obama?

- Is Obama’s 2008 “A More Perfect Union” speech in Philadelphia still meaningful?

- What impact has Obama had on improving life for blacks in the U.S.?

- What penalties do the police officers that kill civilians risk?

- Is there a difference in the behavior of residents in the northern vs. the southern states?

- How do black Americans feel about the term “Afro-Américain?”

- Why hasn’t the pan-African unity promoted by Marcus Garvey gained more widespread acceptance?

- Is voting a viable means of improving conditions for black Americans?

- Are police officers just pawns? Have they been given a mission to protect only whites?

- Is state violence ever necessary?

- What is the position of black police officers?

- With the Ku Klux Klan and the police shootings aren’t blacks afraid to live in the U.S.?

- Is this a safe time for francophone blacks to visit the United States?

The sponsors were very pleased with my presentation and responses to the questions so we had a festive lunch after the event. I had read that Guadeloupians have the highest per capita consumption of champagne in the world so I had been a little concerned about celebrating with them as a non-drinker. Several bottles of wine and local rum were shared during the luncheon but in short order I saw that people were not drinking to get drunk and I was able to relax and enjoy the convivial atmosphere as I sampled another beautifully presented vegetable platter.

After lunch Hubert Jabot, the League president and Patrice Ganot, the secretary accompanied me on a tour of the Memorial Acte museum (http://fr.memorial-acte.fr/home-page.html), which is dedicated to the history of slavery. The museum is built on the site of what was once the largest sugar refinery in Guadeloupe.

Hubert’s nephew, Yannis Songeons conducted the tour. I was impressed with his enthusiasm and with how well informed he was. I especially appreciated the research into the Amerindian history of the Caribbean. 25 years ago when I was pursuing my graduate research on French colonialism in the Caribbean, there wasn’t much information available about the indigenous populations. The Memorial Acte museum features artifacts from Arawak and Carib daily life while the tour provides interesting details about their culture and social organization.

One intriguing feature of the museum is that in addition to historical artifacts it also presents contemporary artworks that were commissioned as responses to the slavery experience. Some of them are very abstract yet they still convey the emotional dimensions of the experience in a way that helps visitors reflect on and process the stark reality of slavery.

After visiting the museum I got about two hours to decompress back at the hotel, then Patrice picked me up and brought me back downtown for the Ilot Jazz concert featuring the black American jazz singer, Rachelle Ferrell. Much of the soundtrack for my sojourn in Guadeloupe was African American soul music of the 1960s. While my hosts, who were mostly of the generation that came of age with this music, also had a great appreciation for jazz artists like Coltrane and Miles Davis, I was struck by the profound impact the Civil Rights movement in the U.S. had had on their consciousness and by the fact that the whole world is still watching our struggle for equal justice. A set of old school funk was slated to follow Rachelle Ferrell but I pleaded fatigue so Patrice dropped me back at the hotel around 10pm.

12/11/16

The next morning we were off bright and early to catch the ferry to Marie Galante, one of the islands that belong to Guadeloupe. In my graduate studies I had read a collection of Kréyòl folktales from Marie Galante that Léon G. Damas had translated into French so I was excited to see another place where Brer Rabbit had been a folk hero. As we boarded, my hosts asked if I were prone to seasickness. Never having been on an ocean voyage before, I said, “I don’t know.” At first I went up on deck with Patrice. The water was rather choppy but it felt like a log flume ride complete with exciting bursts of sea spray so I had some good laughs until the waves started to get really rough. Then we went downstairs and took seats with Hubert and his wife for safety. The passage normally takes 40 minutes and after a while the waves subsided a bit but ironically that was when I started to feel seasick. Fortunately I managed not to lose my breakfast and before long we were being welcomed by Mme. Maryse Etzol, la Presidente de la Communauté des Communes de Marie-Galante.

Following a reception where I was urged to try local fruit juices, there was a question and answer session. Here I found the most interesting questions were about the role that Michele Obama might play in the future.

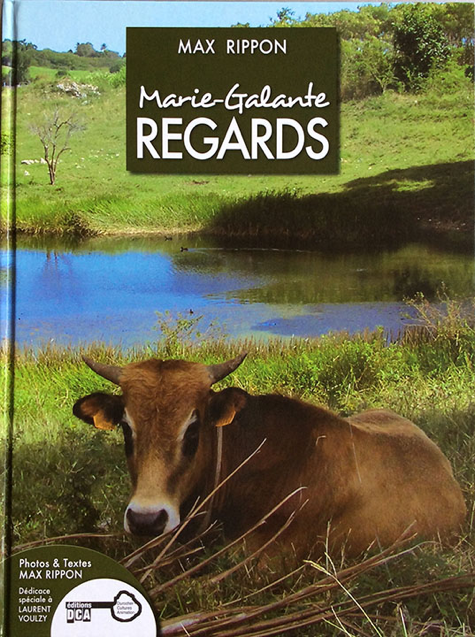

My hosts seemed pleased with my performance and Mme. la Présidente presented me with a beautiful book that highlights the culture and landscape of Marie Galante.

The Communauté des Communes had also organized a tour of the whole island for our party so we piled into a van and set off.

The first stop was the former plantation of a M. Murat who had married a Creole woman from Marie Galante in the 17th century and had made sizeable investments in developing the property that came from her family.

There are three stone mills on the property as well as an imposing stone mansion with a commanding 360 view. I thought about the arduous effort it must have cost to haul those stones up the mountain to the site.

Today the house is a museum. I had many questions because I studied this period of French colonialism as part of my dissertation research and M. Pierre Cafournet, our guide was very knowledgeable about the history of the family and the property. After a quick tour of the exhibits inside the museum, he showed us the pond that had been central to the life of the plantation.

Despite a proliferation of evergreen plants, Marie Galante is a very dry island where people have long used ponds as a way of collecting and managing the sparse rainfall. There was a legendary fromager (kapok tree) growing next to this pond so they encouraged me to stand next to it for a photo opportunity.

The fromager has great significance in the African-derived belief system that has coexisted with Christianity since the arrival of enslaved Africans in Guadeloupe. The Amerindian population considered the whole island of Marie Galante as a sacred site and this particular tree has a special reputation in the local folklore, as does the whole property.

Every year there is a music concert on the grounds of the Murat plantation. While there are often rainstorms during that time of year, our guide noted that the concert has never been rained out. He described times when rainstorms had soaked other parts of the island while the concert took place in clear weather and other times when the day of the concert had dawned with rain, only to see the rain cease during the concert before resuming with the last note.

From the mystical fromager we walked to a site where they are building a replica of a slave house.

On the way back to our van we passed some fruit trees so I was encouraged to try jujubes for the first time. I found these small round fruits with green skins and crisp white flesh delicious.

The next stop was a gathering of farmers who grow pois congo — pigeon peas. Mme. la Presidente used the opportunity to speak with her constituents while I walked out into the field with one of the farmers where I had the opportunity to pick some pigeon pea pods and taste some raw peas. They were scrumptious!

The farmers are experimenting with pigeon peas as an alternative source of protein, which, as a vegetarian, I could greatly appreciate. Having weeded and picked a lot of beans on Rashid Nuri’s Truly Living Well Natural Urban Farms (http://trulylivingwell.com/), I also appreciated the fact that pigeon peas grow on a tall bush so that you don’t have to stoop to harvest them.

Despite this awareness of plant-based nutrition, however, livestock are ubiquitous on Marie Galante. People commonly keep goats tethered in their front yards – no need to mow the lawn when the goats’ grazing keeps the grass cropped. I saw flocks of chickens roaming the grounds of an elementary school and our next stop was a competition between ox teams to see which one could pull a loaded cart up a steep course in the shortest amount of time.

While the traditional oxcart had almost died out for a time, today these ox team competitions have become a very popular sport. Many local residents had turned out to watch the races, socialize, and enjoy a variety of foods.

None of these animals are raised on factory farms so I complimented the head of the ox team league for the ethical treatment of the animals involved.

Thirty years ago I read an article in El Obrero Revolucionario about how U.S. aid initiatives had eradicated the hardy cochon créole from Haiti in favor of breeds imported from the U.S. that were not well adapted to the terrain and that required more expensive care and feed than most Haitian farmers could provide. I was therefore thrilled to see a relative of this extinct species in the flesh.

These pigs are called cochons planches or plank pigs because they are lean and sleek. Most of them are also black or dark brown so for the first time I understood that the legendary black pig sacrificed to the Vodun spirits at the start of the Haitian Revolution was just one of the ordinary local pigs, not a specimen chosen for its supposedly diabolical color.

We were scheduled to have lunch at this event celebrating the production of livestock but I was still able to enjoy a vegetarian meal – this time it was lentils with rice.

During my presentations I had been repeatedly asked if I was afraid to live in the United States and if I were afraid that rate of violence against black Americans would increase under the Trump administration. Participating as a spectator at this ox team competition brought home to me for the first time how much fear I live with on a day-to-day basis as a citizen of color in the United States.

The ox team competition was a rural community gathering similar to what I imagine tractor pulls in the U.S. would be like.

I would have resisted attending a tractor pull, however, because my perception is the devotees of this sport are mostly “rednecks.” Whether individual tractor pull fans are virulent racists or not, I would not have felt safe in such company and I would definitely not have been to anxious to share a meal amongst them even if I had been offered a vegetarian dish. On Marie Galante, however, I felt relaxed and comfortable to a degree that I have never experienced in my homeland. I was able to appreciate the subtle flavor of the food as well as the rich conversation.

Over lunch Patrice questioned me further about my abstinence from sugar and he got an earful. Since he works in agricultural development and has experimented extensively to improve sugar production in Guadeloupe, I got an earful back. I appreciated this exchange because I got another well-informed perspective on an issue that I have studied extensively and on which I have held strong opinions for a long time.

One of my big objections to sugar is that because it has to be processed shortly after harvest, growing sugar as a cash crop requires a considerable investment in a processing plant. As a result, sugar has tended to be cultivated on large estates owned by plutocrats and thus, in most societies that have relied on sugar cultivation, the land tenure system tends to be a source of profound inequality. I cited the case of Martinique during WWII when the U.S. imposed a blockade. Most of the best land was owned by the large sugar planters who continued growing sugar and stockpiling it in their warehouses even though they were unable to sell their crops for several seasons. During this time, the general population who had only small plots of land were unable to grow enough provisions to make up for the lack of food imports so there was great food insecurity and hardship on the island. Patrice said that in Guadeloupe there were fewer large landholders and that in effect, the state had become the largest landowner after emancipation. Consequently the agricultural sector had had more flexibility in responding to the blockade.

Patrice also emphasized the role that sugar plays in the local identity and culture and the essential place it holds in the island’s economy since it is the most valuable export. He said that while the black population had resisted returning to the cane fields after emancipation, today people are reclaiming sugar as part of their heritage. Finally he argued that the locally processed sugar is a very different product than refined white sugar that has been stripped of all nutrients and that the health consequences of consuming the local sugar are not likely to be as detrimental as the consumption of refined sugar. I stuck to my vows against consuming sugar for the rest of my visit but if I return I might be willing to sample some fresh cane juice.

Given what I had heard about the dearth of rainfall on the island, I had asked if there had been traditional irrigation systems that tapped underground sources of water. The answer to these questions was “no.” When the rain fails, the sugar crops also fail. After lunch our guide took us to see a solar powered pumping station, however, that the local government had established to enable farmers to water their livestock during droughts.

Indeed there were rooftop solar cells on many of the houses we passed. There is a high degree of ecological awareness on Marie Galante and a growing interest in promoting eco-tourism on the island. One of our stops included a beach that had once extended for meters that shows visible evidence of global warming as the rising sea has left only a narrow strip of sand beside the road.

We also visited a nature preserve with spectacular rock formations:

and a mangrove swamp at the mouth of one of Marie Galante’s two freshwater rivers.

The beauty of sites like these made me think about the difficulty the National Park Service has had in attracting black and Hispanic visitors to the National Parks in the U.S. Here again I recognized the level of fear that consciously or unconsciously permeates our lives.

We don’t go camping not because we are afraid of the wild animals we might encounter in the woods but because we are afraid we might have unfortunate meetings with Klansmen in these isolated sites.

In the midst of our discussion about sugar, I had asked what the Guadeloupians were doing with their bagasse. Bagasse refers to the stalks that are left over after all the juice is extracted from the cane. Traditionally bagasse served as fuel in the process of boiling the cane juice down into molasses and crystalized sugar. These days, however, there are processes for transforming bagasse into polymers.

Whole Foods sells disposable plates made of bagasse and there are other initiatives to use bagasse as a bio fuel. Jean-Marc Pasbeau, who was directing our tour listened quietly to my exchange with Patrice but it after lunch we learned that bagasse is a subject very close to his heart. Thus, at the site of a pier dedicated to sport sailing we got a detailed overview of the role of bagasse in Marie Galante.

Pasbeau explained that Marie Galante had no electricity until 1965 when an undersea cable from the power plant on the main island had been laid to connect Marie Galante to the grid. Remembering the 40 minute boat ride that had brought us to the island I thought that was a very impressive piece of engineering. The Marie Galantais have always been a very independent, self-reliant people, however so their goal is to become self-sufficient in their capacity to generate electrical power. They are currently in a hot debate about the best method to achieve this goal. There is now a power plant on the island that burns bagasse while it is in season and then imports coal the rest of the year. Some parties object to the importation of a fossil fuel that contributes to climate change and also leaves Marie Galante at the mercy of market fluctuations in the price of coal.

The French government has set up an experimental wind farm on Marie Galante with a bank of lithium batteries that are capable of storing excess capacity generated by the turbines.

We went to visit les éoliennes, poetically named after Aeolus the Greek figure mentioned in the Odyssey and the Aeneiad as the keeper of the winds. While some of the neighboring residents have complained about the noise the turbines make, proponents of wind power hope that in the future it will not only supply all of the islands’ needs but also enable Marie Galante to sell surplus power back to the grid.

At the Murat plantation we learned that while Marie Galante had been nominally under the control of various European powers over the course of its history most of the time the island has functioned with relative autonomy. Since it lacks a harbor with strategic importance and does not boast any natural resources that could be easily exploited, the colonial overlords governed the island with a very loose rein. After emancipation the plantations were very quickly divided up into small freeholds. Thus the self-reliance of the Marie Galantais has had a strong basis in local food production. Therefore another important stop on our tour was an artisanal processing plant that produces manioc flour and coconut flour, two traditional products that are enjoying renewed popularity with the growing interest in gluten-free food.

The sweet aroma of toasted coconut permeated the processing shed when we stepped inside.

Natacha Durin, the proprietor explained that they had completed a large batch of manioc flour in the morning and shipped it all to the main island to fulfill contracts they have with grocery chains and other businesses.

Madame had learned the processing techniques from her mother and grandmother and was committed to carrying on the tradition despite the arduous workload. Like most artisanal producers under global capitalism, she is hamstrung by the labor-intensive nature of the production process.

She lacks capital to invest in equipment that might enable her to produce more efficiently on a larger scale but also feels some reluctance to adopt such methods because her primary concern is with the nutritional value of the product.

Similar issues complicate efforts to re-launch traditional indigo production on Marie Galante. Growing awareness of the negative impact synthetic dyes can have on human and environmental health has led to a resurgence of interest in organic pigments like indigo. Our last stop was the site of a former indigo dye pit.

The Marie Galantais would like to redevelop indigo production as another source of revenue but are just in the beginning stages of the project. Overall I was struck by the timeliness of the Marie Galantais’ traditional wisdom about how to manage natural resources.

12/12/16

The next morning Patrice picked me up bright and early and drove me across from Grand Terre to Basse Terre. These two main islands are close enough together that they are connected by a bridge. The roads are narrow in Guadeloupe and are often overwhelmed by the volume of traffic so traffic jams are a frequent problem but we arrived in plenty of time to prepare for my presentation to several classes of English students at the Lycée Gerville-Réache.

We were scheduled to present in a large room that had excellent audio-visual facilities and a technician on hand to ensure that my slides and audio clips could be seamlessly integrated into the presentation.

Police shootings of unarmed citizens is a very heavy topic and I wanted to leave the students with some sense of hope for the future so I started off by playing “Rap Battle #1” from the hit musical, Hamilton. I wanted the students to see that the younger generation in the U.S. is increasingly multi-cultural and tolerant of diversity. I hoped that the hip hop beats would engage their interest and I also planned to use the cabinet battle as a point of departure for the commentary I wanted to make about systemic racism.

My teaching style is very different from what the students are accustomed to so at first they didn’t know how to respond. After playing the clips, I opened the floor for questions and then used role play to help them understand the historical context behind the police shootings. I chose a robust young man and had the students imagine I had just purchased him at a slave auction. I pretended to be the master, ordering him to pick a bag full of cotton. Then I asked him if he was going to comply. When he said “Yes,” I exclaimed “that was easy! I didn’t even have to whip anybody.” I wanted the students to understand that the only way masters were able to impose their will on the human beings they enslaved was through violence. So I repeated the role play calling for volunteers who were willing to resist. Then I acted out the punishments they might receive for resisting.

I continued the role play exercise to illustrate the development of the sharecropping system (which also existed in Guadeloupe after emancipation in 1848). “You don’t have a place to live or any money to buy food” I said to a student I had chosen to represent a new freedman. “Would you like to come work for me?” When he agreed I acted out the settling up at the end of the cotton harvest “one for me, one for you, two for me, one for you, six for me, one for you – and by the way, you bought flour, sugar, and fabric to make new curtains for your cabin from my store so you owe me money. This coming year you’ll have to work for me for free.”

In the role of the plantation owner I recruited other students to come work for me for free. When I found a resistor I said “o.k., I’m going to put on my white sheet and I’m going to cut two eye holes in a pillow case and put it over my head so you can’t see who I am. Then I’m going to ride out to your house at night and burn a cross in your yard. Are you going to come work for me?” I signed up a lot of people just with that threat but I encouraged the students to volunteer to resist and when I found a resistor, I acted out a lynching, then asked the victim’s neighbors if they were ready to come work for me. The students got the point.

In my opinion, Driving While Black, stop and frisk, and the police shootings of unarmed black citizens have their roots in the system of “paddyrollers” who combed the roads in the south to make sure that slaves and their descendants did not escape from the plantations. I illustrated this with another role play. I chose a student to receive an enthusiastic letter from a relative talking about the Chicago Defender and the opportunities it advertised for good jobs up north. Then I reminded the student that she owed money and couldn’t just resign from working on the plantation. When she took to the road after dark, I stopped her and asked “where are you going?” “The toilet?” she replied. That was a precious moment of comic relief.

From there I did some role plays of contemporary police stop and search tactics. I asked one girl to “step out of the vehicle.” When she stood up, she was shaking like a leaf and she immediately put her hands up even though I hadn’t asked her to do that.

I was amazed at how moved the students were. I haven’t talked to any young people in this country about the police shootings. I suspect that here we tend to dissociate from it because it is too frightening and painful to think about on a day-to-day basis. These students were outraged, however. The lighter skinned ones were visibly red with emotion. There was one boy in the corner who was crying. I couldn’t get him to open up about what he felt and I was worried he might have known someone who had been assaulted by the police.

Finally I chose another volunteer, had him put his hands flat on the desk like they were up on the dashboard where the police could see them. When he reached for his pencil case to pull out his pretend license and registration, however, I blew him away exclaiming, “he’s got a gun!” Once again we laughed but I explained, “people have died like that.”

After the role play we had more questions and answers. Then Patrice and I went to lunch with the principal and some of the staff.

I was glad that I was once again able to eat enough to be sociable. Then we headed back to Point à Pitre.

Patrice took the scenic route along the coast. He was full of information about the culture and history of the sites we passed so the drive was a very rich experience in both directions. He also managed our time very well so we were in plenty of time for the next presentation at the Lycée Jardin d’Essai in Point à Pitre. They were not nearly as well-organized, however. The room we were supposed to be in was locked and no-one could find the person who had the key. While we were sitting outside, I got another chance to talk to M’Bitako, a gentleman who had attended my first presentation and had asked about Obama’s 2008 “A More Perfect Union” speech. Turns out he had translated the speech into Kréyòl.

When M’Bitako presented me with his Kreyol translation of “A More Perfect Union,” I remembered teaching this speech in an ESL class. I had only ever experienced this discourse on paper, however. Throughout my visit whenever people asked me about Obama’s legacy, I said that the only thing I had hoped was that he would be able to finish his term without getting assassinated. Since he lived out his second term, I count his administration as a tremendous symbolic success. Yet my interactions with people like M’Bitako in Guadeloupe underscored for me once more the level of constant fear I have lived with in the United States. We elected a black president but I couldn’t to invest too much in his administration because the pain of losing him to an assassin’s bullet would have been unbearable.

When we finally we got into the classroom where I was supposed to present, we couldn’t get the AV equipment working. I ended up starting the session by teaching the first part of “Ella Baker’s Song” by Bernice Johnson Reagon:

We who believe in freedom shall not rest

We who believe in freedom shall not rest until it comes

Until the killing of black men,

Black mothers’ sons,

Is as important as the killing of white men,

White mothers’ sons

We who believe in freedom shall not rest

We who believe in freedom shall not rest until it comes

I made everybody sing, did more role plays, and fielded questions even though we only had an hour.

At the end I played “Rap Battle #1” on my laptop, walking into the crowd while holding it over my head so everyone could hear. Julien received enthusiastic appreciation from both schools immediately after the presentations so I felt glad that I had been able to acquit myself well.

12/13/16

The following morning my hosts had left my schedule open for an activity of my choice. I had indicated an interest in the historic costume of Guadeloupe and as it turned out, there is a museum dedicated to this subject. I got up early and spent an hour walking up and down on the hotel’s little strip of private beach. The phone was ringing when I got back to my room. After playing phone tag Patrice had been able to contact Claude Bausivoir, the owner of the museum and schedule a tour. Could I be ready in half an hour? I jumped through the shower and was waiting downstairs at the appointed time.

The museum turned out to be an excellent resource not only on traditional costume but also on lifestyles and mores. Mme. Camélia Bausivoir-Garcia and her husband, Claude launched it with objects and garments from their personal collection, then acquired more artifacts and expanded the exhibits. In addition to the two exhibition galleries they have also created replicas of a traditional outdoor kitchen and a case (a traditional cabin) on the property. I was impressed that the tour begins with an overview of all the cultures that contributed to traditional Guadeloupian dress from Aztec and Inca nobles to ancient Greek draperies and Roman togas.

Most of the museum’s visitors come with school groups so Mme, a former English teacher who made her first communion in 1958, had a lot to say about the state of the younger generation, especially the fashion for sagging jeans. One of the exhibits shows a mother working at a treadle sewing machine while her five-year-old daughter plays at her feet. Mme. remembered learning to embroider and sew at a very young age and lamented the fact that today’s children do not have any kind of handiwork as part of their regular curriculum in school. She talked about the personal discipline and work ethic of women in earlier generations who kept neat and tidy homes while working a variety of jobs and often walking miles between them over the course of a single day. She stressed the importance of a well-regulated household for the physical and mental health of the family and asserted that the traditional styles of dress had fostered a better sense of body image and self-confidence. Many of the young students who come to visit the museum do not even know where their waists or other parts of their bodies are because they only wear today’s relaxed styles.

As a passionate lover of hats one of my favorite exhibits was the case full of hats and traditional madras coiffes. Dou douist legends about exotic island women have made much of the notion that the number of points in this headdress indicated the wearer’s marital status. Mme. Bausivoir-Garcia asserted that this “language of the coiffe” has been grossly exaggerated and that to the extent that it did exist, it was a Martinican phenomenon rather than a Guadeloupian custom. She said the real language was the language of fabrics and pointed out different ensembles in a variety of fabrics and textures with explanations of why they were appropriate for specific occasions. For example on the occasion of a child’s first communion, a mother wouldn’t wear a bright color like red because the focus of attention was supposed to be on the child and the solemnity of the ceremony. The mother in the first communion scene wears a lavender outfit instead. I have always enjoyed the semiotics of dress so I greatly appreciated Mme.’s observations on the signification of traditional Guadeloupian dress.

By the time we had finished touring the two interior galleries, M. Bausivoir had arrived. He interpreted the external exhibits for us. In the kitchen scene he pointed out a washtub by the Chappée company. It had an agitator in the center that supposedly made the work easier and more efficient. He showed us one of their classic advertisements which, like the Gold Dust Twins campaign in the U.S. presented a caricatured black person being washed snow white thanks to the product. This image was disturbing but the ad had so permeated the popular culture of the time that Guadeloupians still use the term “peau chappée” to refer to light-skinned people like Patrice.

At this point I got a further lesson into the significance of color and class in Guadeloupe. Patrice is fair with wavy hair. My hosts told me he is “mulatto” while Obama is “metis.” That is, a person who has parents of two different races is “metis” or mixed but a person from a family that has been mixed for generations belongs to the mulatto class. In the French Antilles, the mulattos were traditionally the clerks and intellectuals. Patrice’s grandfather started as an apprentice in a print shop that printed a lot of official materials for the colonial government. He rose to be the director of the enterprise. Patrice’s father was a doctor who started a clinic in Basse Terre.

I would have liked to spend more time in the museum but the owners had another appointment and had opened especially for us so we left shortly after 11. This gave us plenty of time to stop for lunch in Patrice’s favorite restaurant before our final round of duties in Sainte Anne.

Like many intellectuals of their era, Patrice’s father and grandfather were both sympathetic to the Communist Party. Patrice still describes himself as an extreme leftist so it’s not surprising that his favorite restaurant is a small spot frequented by people of modest means who appreciate the flavorful meals. It didn’t have a view of a pleasant garden like the restaurant where we lunched in Basse Terre. Instead of contemporary fine art works on the walls, it was decorated with reproductions of local cartoons. The chef was able to produce a vegetarian platter, however, so I was able to do justice to Patrice’s hospitality.

Sainte Anne is on the beach but we drove along a road that winds up and down the ridges and valleys in the foothills of Grand Terre so I had the opportunity to see another part of Guadeloupe’s varied terrain. After a brief meeting with Mayor Christian Baptiste, we piled into an official vehicle and began our rounds.

The main street in Sainte Anne fronts on the beach so on our first stop I was invited to “touch the water.” I took off my shoes and waded in but the waves were very high and in short order the water splashed up on my skirt so I came out. Hopefully the mayor’s photographer had time to get a good shot.

Next we walked a few blocks to a school that teaches sailing and swimming. We talked briefly with the owner, then I was introduced to a man who heads an organization for Guadeloupians of Indian descent. He brought another interesting perspective on identity politics, emphasizing that he sees himself as Guadeloupian first and explaining that because most of the Indians who came to Guadeloupe as indentured laborers were Tamils from rural areas, Divali was not one of their traditional practices. Instead this holiday has been imported like Halloween in the last twenty years or so.

I made an analogy with Kwanzaa which is a holiday invented as an African American alternative to commercialized Christmas. We didn’t have time to discuss all the ramifications of such “inauthentic” practices, however because the next activity was in fact, a foray into one of the most authentic aspects of traditional Guadeloupian culture — a Gwo Ka school.

Gwo Ka, which translates as Big Drum, is the traditional music of Guadeloupe. The themes of Gwo Ka songs express the outlook of the people in much the same way as the blues express an African American worldview. The instruments are adaptations of African instruments with new materials. I saw one instrument made of small, conical woven baskets full of seeds that reminded me of the caxixi in Capoeira only there were two baskets joined by a U-shaped rod. There were some gourd instruments, a variety of drums and some wooden blocks that sounded like claves.

A children’s class was in session when we arrived. We listened to them drumming for a little while, then the instructor called for volunteers to lead some songs. The mayor took a turn on the drum and showed his skills while the children sang.

Then the instructor had them demonstrate another instrument – the strombophone. The strombophone is a brightly painted conch shell with a wooden mouthpiece glued to one end. The students had some trouble getting a sound out of it but what my hosts didn’t know is that my father was a trumpet player so when they invited me to try the strombophone, they were very surprised and charmed that I was able to produce a strong, clear tone.

The Gwo Ka school had also prepared a little reception for us with food and fresh fruit juices but I managed to evade the refreshments by getting people to show me dance steps. I am never comfortable when presented with new foods but I can readily embrace any new cultural experience that involves music and dancing! Receiving a strombophone as a gift was the highlight of the whole wonderful visit. Still we had one more stop to make before my final presentation.

Up on a ridge above the town we visited another atelier producing artisanal manioc flour. Widy Grego, the owner is an endurance runner who has studied manioc production in Brazil and West Africa in order to refine his own ideas about how to re-introduce this traditional staple.

Grego was very articulate about his subject, beginning with the story of how manioc production had become a source of pride in the black community in the time of Governor Constant Sorin (1940 – 43). While the population of Martinique suffered great hardship due to the American blockade, black Guadeloupians re-purposed existing materials like sugar cane kettles to set up manioc processing plants that made manioc flour a viable local food source.

Grego has been studying ways to make the production less labor intensive that don’t require large capital investments or sacrifice the artisanal quality of the product. He is in the process of constructing a new plant on his family’s land but to date only the reception room is complete. (Visit Espace K’SAV https://www.widygrego.fr/)

Still our party appreciated the opportunity to taste Grego’s product in the form of griddle cakes (somewhat like tortillas) filled with coconut preserves or cheese.

Like Natacha Darin, Grego is positioning his product in a market that is increasingly appreciative of gluten-free foods. He has developed his processing methods to produce finer flour suitable for crepes and has also developed several flavors of gluten-free cookies that he sells along with his flours in a stand on the beach.

Back on the beach Grego introduced us to his apprentice, a young man who had grown up on the streets, accumulating an extensive rap sheet along the way. One day Zidane sat himself down by Grego’s stand and returned to sit there quietly day after day until Grego started talking to him and began entrusting him with small responsibilities. He now runs the stand while Grego is occupied with other business and takes pride in work that promotes the heritage of his country.

Widy Grego touts his manioc flour cookies with apprentice Zidane at his side – photo by Patrice Ganot

The last question and answer session was the most difficult. My French was more fractured because I was too tired to think of technical vocabulary. This meeting was also with the heads of different civic organizations in Sainte Anne so these seasoned leaders asked more probing questions than I had received before.

One lady was very insistent on the question of why no great leaders like those of the Civil Rights Movement had emerged and why black Americans were not more active in demanding an end to the police shootings. Questions like these left me questioning myself long after the session was over.

I confessed that before I received the invitation to speak on this subject in Guadeloupe, I had not been paying much attention to the police shootings and the Black Lives Matter movement. I said that because these killings occur so frequently I think that most of us tend to dissociate in order to be able to get through our daily lives. She thought I meant that black Americans are too busy chasing the Almighty Dollar to organize and stand up for our rights. I could not talk about the intense grief work I was doing with my therapist last spring to resolve my trauma over people I had known who went missing 50 years ago. Nor could I refer directly to the fact that every time someone’s brother or son or cousin is killed by the police, it is a trigger for me. Still her outrage and her questions made me ponder how many of us have constant post traumatic stress from living with the knowledge that any one of our lives could be snuffed out at any time in this way. How many of us have directly experienced this type of violence and are paralyzed by even more acute degrees of post traumatic stress as a result?

As the conversation progressed, I did bring up the psychological dimension, however, with reference to Frantz Fanon, the revolutionary psychiatrist from Martinique. I wrote my dissertation on Fanon and Mayotte Capécia so when another man asked me about the question of personal responsibility, I was able to tie a number of threads all together. For me the struggle for human rights begins with having a strong enough sense of your own worth to advocate for yourself. In the question and answer session following my first presentation, there had been a long, rambling comment about health and different practices for sustaining it such as meditation. My hosts had not deemed that intervention worthy of a response but I thought it was a valid point and I referred back to it in this final discussion. I said that many activists of the Civil Rights era had burned out because they didn’t take care of their health. They didn’t sleep. They didn’t eat regular, healthy meals. Many of them got mixed up in abusing drugs and alcohol as a way of coping with the stress. I said that in order to be effective over the long term, you have to value yourself enough to take care of yourself.

Continuing on the subject of Fanon, I also pointed out how difficult it is for African Americans to get good mental health care because there aren’t that many professionally trained black counselors like Fanon. Counselors who don’t share our background often haven’t received any professional training that would make them sensitive to our cultural outlook and therefore it is difficult to build the trust and rapport necessary for a supportive therapeutic relationship.

I said that many victims of police shootings have certainly exhibited poor judgment but that everyone has committed minor infractions of the law at some point like exceeding the speed limit or forgetting to renew your registration and insurance. I didn’t say the word “respectability politics” but I did say that no-one deserves to die for those kinds of bad choices. I also talked about the importance of having a supportive family and community environment as a child in order to develop the sense of being a person who is worth something. I noted that cultural traditions like what I saw at the Gwo Ka school help children develop that kind of self-esteem but that children who don’t have the benefit of such resources have a harder time making good choices.

Finally I referred to Zidane, M. Grego’s apprentice. They told me he had said that when he was living on the streets, he needed to make sure people were afraid of him in order to survive. In a society like ours where guns proliferate, a young person like Zidane would have been forced to arm himself and might have ended up using a firearm to solidify his street rep. Doing so would have condemned him to a lifetime in our criminal justice system. He probably would not have had the opportunity to rehabilitate himself that he has created by seeking out M. Grego as a mentor.

At the end of the session Mayor Baptiste asked me to demonstrate the gift I had received. I raised the strombophone to my lips and blew a long clarion call that still echoes in my ears as I ask myself how I can continue to affirm that black lives matter.

Gluten-free

Manioc Flour Cookies

½ cup Earth Balance vegan buttery spread

½ cup coconut oil

½ cup honey

½ cup date sugar

½ cup applesauce

2 tablespoons lemon zest or grated lemon peel

1 teaspoon Simply Organic lemon flavor

½ teaspoon salt

2 teaspoons baking soda

3 cups manioc flour

½ cup coconut flour

Let the buttery spread and honey reach room temperature. Then preheat oven to 400 degrees Fahrenheit.

Sift all dry ingredients including the date sugar together and blend well.

In a mixing bowl cream the honey into the buttery spread. Stir in the applesauce. Then add the lemon flavor.

Gradually stir the dry ingredients into the batter. It should form crumbly clumps of dough.

Scoop up a teaspoon of dough, then roll it into a ball and place on a greased baking sheet.

Bake for 10 – 15 minutes until lightly browned.

Yields about 5 dozen.

=======

[1] Ingraham, Christopher. “Our infant mortality rate is a national embarrassment” The Washington Post. September 24, 2014.

https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/wonk/wp/2014/09/29/our-infant-mortality-rate-is-a-national-embarrassment/?utm_term=.10302a01febf accessed 120616

[2] Walker, Tim. “Why do so many murders of young black men in the US go unsolved?” Independent Monday March 9, 2015

http://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/americas/why-do-so-many-murders-of-young-black-men-in-the-us-go-unsolved-10096763.html accessed 120616

[3] Rice, Zak Cheney. “64,000 Missing Women in America All Have One Important Thing in Common” Identities.mic. July 16, 2016.

https://mic.com/articles/93780/64-000-missing-women-in-america-all-have-one-important-thing-in-common#.FnnE8fjlM accessed 010117