She changed the way

America saw black people

When Ming Smith was a teenager in 1960s Columbus, Ohio, her high-school counselor told the Detroit native to abandon her ambitions.

“He said, ‘All you’re going to do is be a domestic,’ ” the photographer, who now lives in Harlem, tells The Post. “ ‘Why waste going to college?’ ”

Instead, Smith went to Howard University in DC, moved to New York City and became one of the foremost chroniclers of black life in the US and beyond. She’s now the subject of a major solo exhibition, opening Friday at the Steven Kasher Gallery in Chelsea with 75 photos on view spanning her 40-year career.

“I had a teacher who used to tell me, ‘Always be in the art,’ ” says Smith, whose impressionistic images capture the grit, poetry and vitality of communities from Coney Island to Senegal. “I photograph from my heart — it’s impulsive, but it’s constant.”

Smith, who declines to give her age but is in her 60s, fell in love with photography in kindergarten, when she borrowed her parents’ Brownie camera for her first day of school.

“I just took photos of my classmates,” Smith says, adding that she got the idea from her pharmacist father, who loved taking pictures of the family during special events. She found that photography allowed her to observe, and even communicate with, others while remaining a bit of an outsider.

“I was always very shy,” she says. “[Photography] was a way I could divert attention to another person.”

But people still noticed Smith. When she was in college, Muhammad Ali, who was giving a lecture at Howard, noticed the beautiful student hiding behind the scrum of photographers with her camera in hand.

“We would talk about the negative images that were out there representing American black people that weren’t being made by [blacks]. We wanted to change that.”

“He said, ‘You, come up here! Take my picture!’ ” Smith says. “I have no idea if it even came out. I just took it as fast as possible so I could get away.”

Smith graduated with a degree in microbiology, but when a friend told her she could make $100 an hour modeling in New York City, she high-tailed it to the West Village where, in between go-sees and catalog gigs, she fell in with a group of young black photographers who would go on to create the African-American collective Kamoinge.

“We would talk about the negative images that were out there representing American black people that weren’t being made by [blacks],” Smith says. “We wanted to change that.”

For example, Smith noticed she rarely saw black families being portrayed in the press, so she began snapping pictures of mothers and children, fathers and their babies, and siblings running, laughing and smiling.

“A lot of the people I’d photograph, they were struggling, but there was life there,” says Smith. “They were optimistic and full of love.”

She shot her pictures on the fly, letting them streak and blur and thus imbuing them with an intimate, dreamlike quality that straddled the line between documentary realism and impressionistic art. In 1978, she became the first African-American female photographer acquired by the Museum of Modern Art, which mistook the artist for a messenger when she went to drop off her portfolio.

“It was like winning the Academy Award, but no one knew about it,” she says of the honor. “I didn’t tell anyone for years.”

Almost four decades later, Smith has traveled all over the world for her art. She has experimented with collage and painted over her photographs. She’s taken portraits of some of the most iconic figures in modern culture, including Nina Simone and Grace Jones, the latter with whom she modeled in Paris in the early 1970s.

She’s also working on a book of her photography, wants to do a film about dance — her main passion after photography — and still carries her camera “24/7.”

“I just want to continue to express myself through my art,” she says. “That’s the beauty and the struggle of an artist: the work goes on and on and on.”

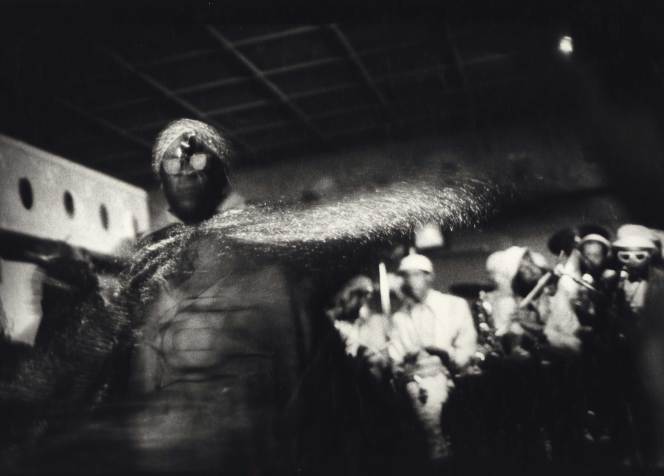

SUN RA

“I went to see him in this small club in New York, and I loved the way the light hit the silver fabric on his cape,” says Smith of her on-the-fly portrait of Afro-futurist musician Sun Ra. “He looks like he’s from outer space here. It really represents his music.”

PRODIGAL SON

Smith captured this photo of a man passing by an exuberantly decorated storefront, which includes paintings of Oprah and Martin Luther King Jr., during one of her walks in Harlem.

“The way the light hit [the image of] Martin Luther King, it looked like the sun was passing by,” Smith says.

HARLEM

Smith still draws inspiration from Harlem. While shopping for a dress in a local store recently, Smith noticed the shopkeeper taking money out of the register to give to a customer.

“She told me, ‘He’s been in jail and is struggling to take care of his child so I just want to help him out.’ It was the same feeling you would see 40 years ago.”

>via: http://nypost.com/2017/01/12/she-changed-the-way-america-saw-black-people/