The Distinction Between

Slavery And Race

In U.S. History

The history of the Electoral College is receiving a lot of attention. Pieces like this one,which explores “the electoral college and its racist roots,” remind us how deeply race is woven into the very fabric of our government. A deeper examination, however, reveals an important distinction between the political interests of slaveholders and the broader category of the thing we call “race.”

“Race” was indeed a critical factor in the establishment of the Constitution. At the time of the founding, slavery was legal in every state in the Union. People of African descent were as important in building northern cities such as New York as they were in producing the cash crops on which the southern economy depended. So we should make no mistake about the pervasive role of race in the conflicts and compromises that went into the drafting of the Constitution.

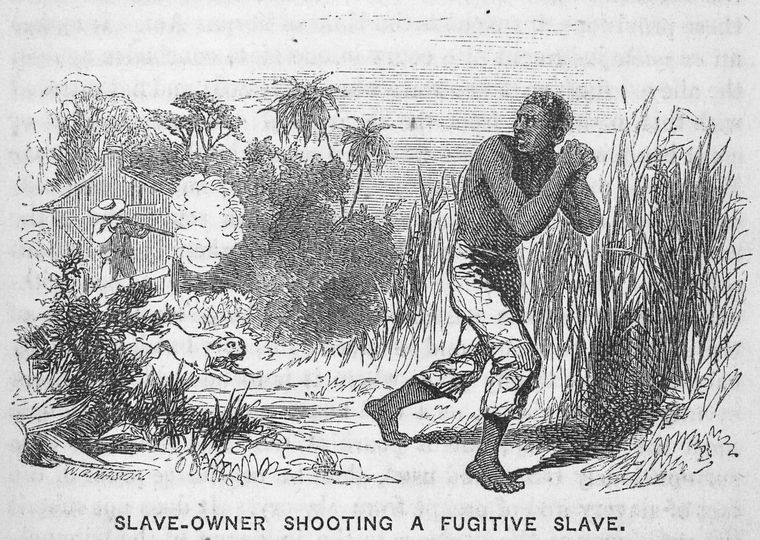

Yet, the political conflicts surrounding race at the time of the founding had little to do with debating African-descended peoples’ claim to humanity, let alone equality. It is true that many of the Founders worried about the persistence of slavery in a nation supposedly dedicated to universal human liberty. After all, it was difficult to argue that natural rights justified treason against a king without acknowledging slaves’ even stronger claim to freedom. Thomas Jefferson himself famously worried that in the event of slave rebellion, a just deity would side with the enslaved.

But the Framers never got to the point of debating black freedom and equality in Philadelphia during the summer of 1787. They were too busy arguing over how much extra power slaveholders would have in the new form of government. As James Madison noted, of all the divides between the states, the one that came to drive debates most was that between slave states and those becoming free. But these debates were over slavery–not race. They were about the political power of slaveholders, not the rights of those enslaved or degraded by the racial identity ascribed to them.

Slavery divided the nation; race, not so much. At the Founding, the argument over slavery was an argument between powerful elites, some of whom depended completely on slavery for their profits and some who did not. While the issue of slaveholder power eventually came to dominate the national political agenda, the question of race — and particularly the racial equality of non-Europeans — did not. Widespread consensus consigned nearly all blacks to sub-citizen status, even when they were not legal property.

Northern emancipation demonstrated how race could thrive even in slavery’s absence. Ending slavery was never easy, but it was easier where slavery was less central to the economy. It was no surprise that New Hampshire, home to around one hundred slaves in the 1770s, ended the institution in 1777, while New Jersey, home to some ten thousand at the Founding, still listed eighteen “apprentices for life” on its 1860 census.

Wherever and whenever slavery ended in the North, freedom generated whole new waves of racial hostility. Slavery, it turned out, rested atop the deeper foundation of a vicious racial caste order. Labor competition between white and black workers unleashed new furies of racial violence. It became possible for European immigrants to leverage their whiteness into a form of symbolic capital that proved quite precious when the real article was scarce. Racial science elicited fears of “amalgamation” while blackface minstrel shows wove denigrating stereotypes into the nation’s burgeoning popular culture.

As a consequence, people of African descent were largely written out of the civic body. In the so-called Jacksonian “age of the common man,” free states dropped property requirements to vote only to add the word “white” to their constitutions for the first time. This removed blacks from the electorate where some had once held the franchise. All new free states entering the union before the Civil War did so without property qualifications for voting, but with explicit constitutional denials of black suffrage: Ohio (1803), Indiana (1816), Illinois (1818), Michigan (1837), Iowa (1846), Wisconsin (1848), California (1850), and Oregon (1859). It was as if whites regardless of class could be welcome in the new America, but only with the sacrifice of blacks’ claim on citizenship. Freedom was a great idea; it was just going to be reserved for white people.

abolitionists offered welcome friends and needed resources. Few white

people, regardless of how marginal, could escape the imaginative

bounds of a pervasive race culture. But as limited as they could be,

moneyed white abolitionists propelled the slavery issue onto the

national stage. From there, they ventured into the very political system

that maintained the accursed institution.It was a move critical to

ending slavery, but difficult to pull off. Slaveholding states’ artificial

advantages in the House of Representatives and Electoral College

combined with a two-party system that wanted to discuss any issue

other than the one that threatened to split their coalitions cleanly in

half. Antislavery activists made headway, but the pervasive racism

around them made building a movement challenging. Experimen-

ting through several iterations over several election cycles, they

eventually hit upon a two-fronted rhetorical attack.First, they

argued that the Slave Power was bent on undermining freedom.

Just as masters coveted power over slaves, so too the “slaveocrats”

sought to trample upon the civil liberties of free white northerners

in their desire for mastery over government. As evidence, they

pointed to the South’s unprecedented use of the federal govern-

ment to protect and expand the institution. Second, they argued

that the western territories should be kept free from slavery in

order to keep it free from slave laborers who would degrade their

free white counterparts.

much for African Americans to embrace them. Antislavery

politicians threw away the dog-whistle and made their case

plainly: “We, the Republican party, are the white man’s party,”

declared Republican Senator Lyman Trumbell. “We are for

free, white men, and for making white labor respectable and

honorable, which it never can be when negro slave labor is

brought into competition with it.” In short, one could stand

against slavery while also being racist. Slavery and race were

not the same thing. And thus we see what is hard to see unless

we can distinguish race from slavery: how an overwhelmingly

racist North came to fight a war to end slavery.This is not just

a story of antebellum days. The Jim Crow South patterned its

segregation laws after ones tested in the North, just as civil

rights challengers to such laws drew on pre-war pioneers. It

was this edifice that the heroes of post-WWII America toppled,

a full century after the Civil War had abolished slavery. Ulti-

mately, then, the Civil Rights tradition is not something that

began in 1954. It has been with us since the first days of the

republic, just as we are in the midst of defending it once again.

There are two lessons I take from all of this. First, we must

end any notion of the free states as morally superior to the

slave states, for that is a calculation that only works if slavery,

and not race, is being considered. It is true that the movement

to end slavery came largely from the free states. But the North

did not honor the abolitionists. To the end the most com-

mitted of them remained a small minority, despised almost

as much as were the free blacks who had inspired them. We

all need to let this one go; there was plenty of karma for

everyone.

Second, we need to look at how the arc of history bent in this instance against progress and expanding liberty, toward a narrower and less tolerant vision of the country. Unfortunately, that happens regularly in our history. It seems bizarre that anyone could believe that democracy is bettered by writing people out of it, but of course, such arguments are today raising unprecedented levels of alarm.

This is a cautionary tale, then. History does not have to move forward. No cosmic force, historical “principle,” or benign deity will save us from ourselves. That is work for us to do.

+++++++++++

Patrick Rael is Professor of History at Bowdoin College. He is the author of numerous essays and books, including Black Identity and Black Protest in the Antebellum North(North Carolina, 2002), and his most recent book, Eighty-Eight Years: The Long Death of Slavery in the United States, 1777-1865 (University of Georgia Press, 2015).

>via: http://www.aaihs.org/the-distinction-between-slavery-and-race-in-u-s-history/

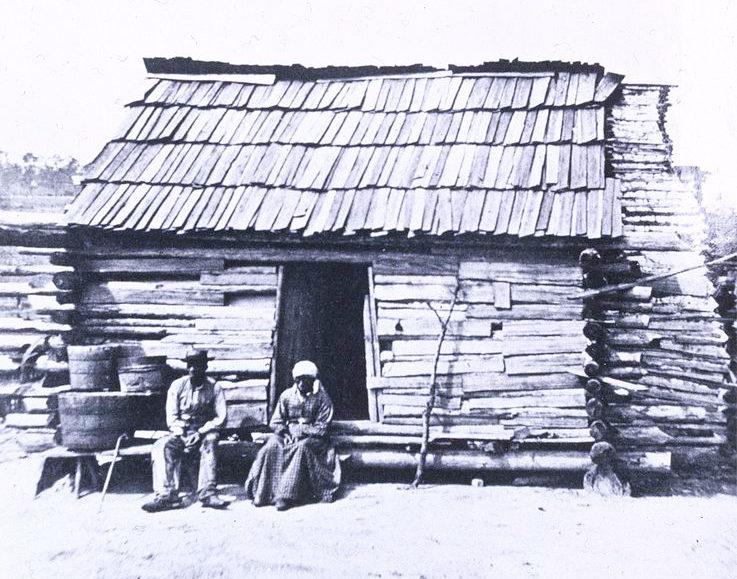

![“Anti-Slavery Meeting on the [Boston] Common” (Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Photographs and Prints Division)](http://kalamu.com/neogriot/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/slave-cabin-02.jpg)