CHAPTER 1: Defining BAM

Definition. The Black Arts Movement is an arts movement whose objectives were three-fold: 1. to establish Black leadership of Black cultural expression directed to a Black audience,

2. to propagate a Black Aesthetic, and

3. to produce socially engaged art that promoted the Black Freedom/Black Liberation struggle.

This definition distinguishes BAM from a simple racialist position that any art produced by Blacks is “Black Art.”

BAM and Black Consciousness. A Black power, or Black consciousness, perspective called for Black leadership and mass involvement; a Black Aesthetic; and socially engaged art which openly advocated Black Freedom/Black Liberation struggle. During the 1965 to 1976 BAM highpoint, all across America via involvement in local neighborhood youth-oriented (preschool to college) organizations, art collectives and community-based arts agencies, Black artists were on the move, attempting to create artwork which spoke directly to Black people out of the above listed triad of Black power concerns. Moreover, this movement was dialectical in that it was not a simplistic following of one premise to its logical conclusion but rather an ongoing, dynamic and constantly developing interplay of theory directing practice and practice, in turn, shaping the development of new theories, and also of individually developed dreams and ideals which were attempted and/or actualized by grassroot groups across the nation who, in the process of making the ideal into reality, created new dreams and ideals.

After the growth of local organizations, the second step in the local/national/local (L/N/L) dialectic was BAM becoming nationally self-conscious. LeRoi Jones’ coining of the name for the movement is indicative of the fruition of this second step. In his autobiography Baraka (aka Jones) recalls:

One evening when a large group of us were together in my study talking earnestly about black revolution and what should be done, I got the idea that we should form an organization. On Guard had been long gone, because of its obvious contradictions. We needed a group of black revolutionaries who were artists to raise up the level of struggle from the arts sector. There was Dave Knight, White, Marion, C.D., Leroy McLucas, the Hackensack brothers (Sammy and Tong), Jimmy Lesser, Larry, Max, plus Corny and Clarence and Asia Toure. We would form a secret organization. Tong asked me what would it be called, it came into my head in a flash, the Black Arts. [page 197]

Note that some of the names used are pseudonyms, specifically Sammy and Tong Hackensack who are really Charles and William Patterson. Also note that “Max” refers to Max Stanford, the founder of RAM, Revolutionary Action Movement. Stanford was a political activist and not an artist. Thus, at its inception, BAM was a marriage of art and politics.

The third step in BAM’s dialectic of development was the adoption of the nomenclature and the general principles by Black and Black-oriented organizations nationwide.

A word about “Black-oriented” organizations is necessary to illustrate the varying levels of development. The Free Southern Theatre (FST) initially was an integrated organization which performed adaptations of “classics” as well as original work. One can easily imagine the bemused, if not confused, reaction of sharecroppers in the Mississippi Delta to the 1964 production of Samuel Beckett’s Waiting For Godot. By 1969 FST was all Black and those same Mississippi Delta viewers were literally and profoundly “moved” by a pre-New York performance of LeRoi Jones’ Slaveship. The audience was aroused to militant action. There were actual civil disturbances following the production. Moving its audience to action was an intended goal of this play and of BAM.

The FST Slaveship example has an interesting footnote. Gilbert Moses, one of the founders of FST, was the director of the FST version of Slaveship which toured the deep south. On the basis of his innovative work on that version of Slaveship (which used a portable set that could be carried in a van and set up in a variety of venues), Moses was tapped to do the Broadway version of Slaveship which played to critical and popular success. Although the nation as a whole became aware of Slaveship as a result of the Broadway success, within the national BAM context, it was the FST production that actually launched Slaveship.

On the one hand, FST was a precursor of BAM, but through the dialectical L/N/L process, FST also became a major proponent of BAM. Those who look for a linear, progressive development and do not take into consideration dialectical developments make a major mistake.

Karamu House, founded in 1949 by the Jelliffe’s in Cleveland, Ohio is another example of local arts movement which both preceded BAM and then became a BAM-influenced institution struggling around the triad of BAM concerns: Black leadership/Black audience, Black aesthetics, and social relevance to the Black struggle.

By 1970 most local, Black-oriented, arts organizations began referring to themselves as “Black Arts” organizations. There was Black Arts/Midwest, Black Arts West, BLKARTSOUTH, etc. That was how BAM developed. Moreover, these organizations generally followed the guidelines laid down in the BAM publications. A July 24, 1975 letter from an aspirant BAM member in Sedalia, Missouri (“a small town in central Missouri (Sedalia) located between St. Louis & Kansas City”) addressed to Joe Goncalves is but one example which clearly illustrates this point. M. D. Briscoe writes:

“We are in the process of setting up a black cultural center to serve the brothers & sisters in this area. Theatre & poetry will be the foundation of our learning media so The Journal of Black Poetry is one of the necessary communication links we must have. Please send information about subscription price & a sample copy if possible, and any information and/or contacts that can help our growth. We are small with much to learn. Our principle goal is to develop Pan-Africanistic thought. All help is needed & will be appreciated. [Dingane / “Letters”]

Goncalves has a clutch of such letters literally from around the world that are similar to the one cited above and that demonstrate how closely people identified with BAM. This is how BAM developed, coalescing from grassroots/local activity, formalized on a national level, reasserted by the grassroots.

Internal Contradictions. When we review the staffs and editorials of BAM journals we find that there is clearly no single leadership, no single line. In fact, if anything, there is an ongoing struggle around leadership and ideology. Sometimes this struggle for ideological leadership takes on a personal tone of ad hominem attacks. Sometimes former allies become bitter enemies and vice versa. By 1970 LeRoi Jones/Amiri Baraka becomes a leading, although not uncontested, figure. However, Jones/Baraka’s popularity notwithstanding, there was no single centralized BAM leadership.

The lack of centralized leadership was both a strength and a weakness. The strength was that BAM organizations could reflect the particulars of their local situation and the local grassroots artists could determine their own specific direction in implementing general BAM guidelines. This contributed to a strong decentralized base of activity nationwide. However, the lack of a central leadership was also a major liability, especially when BAM formations were beset by financial strictures and ideological infighting.

For example, when John Johnson shut down Black World, there was no national leadership in place to negotiate with Johnson on Black World’s behalf nor was there an organization in place to facilitate the development of a new independent literary magazine which could follow up on the now defunct Black World. An effort was made in 1976 to found First World but the new journal was not able to sustain itself and the Hoyt Fuller edited follow-up journal folded after a handful of issues when Hoyt Fuller suffered a heart attack and died in 1977.

Time and again, especially after the lost of key individuals or the closing down of key BAM institutions, BAM adherents were unable to mount an effective national response. The decentralized focus/lack of centralized structure and/or leadership was a major debilitating internal dialectic of BAM.

External contradictions. There was a second disruptive dialectic at work. This dialectic was external and intentionally disruptive. The establishment defunded BAM institutions and established alternative “acceptable” institutions. The target audiences for these philanthropic created (as opposed to grassroots created) organizations was the BAM audience. Baraka points to The Negro Ensemble Company is an obvious example of this trend.

Later, after the word “black” had cooled out some and the idea of even “black art” had sunk roots deep enough in the black masses, where it could not simply be denied out of existence, the powers-that-be brought in some Negro art, some skin theater, eliminating the most progressive and revolutionary expressions for a fundable colored theater that merely traded on “the black experience,” rather than carrying on the black struggle for democracy and self-determination. Then the Fords and Rockefellers “fount” them some colored folks they could trust and dropped some dough on them for colored theater. Douglas Turner Ward’s Negro Ensemble is perhaps the most famous case in point. During a period when the average young blood would go to your head for calling him or her a knee-grow, the Fords and Rockefellers could raise themselves up a whole-ass knee-grow ensemble. But that’s part of the formula: Deny reality as long as you have to and then, when backed up against the wall, substitute an ersatz model filled with the standard white racist lies which include some dressed as Negro art. Instead of black art, bring in Negro art, house nigger art, and celebrate slavery, right on! [Baraka / Autobiography pages 214-215]

Yet, this is not the most insidious example of this dialectic. The most insidious is the development of “Blackploitation” movies to push aside and replace the Independent Black Cinema movement which was an active part of BAM. We will briefly discuss this development in a later chapter.

Notably, the “alternative” and “establishment initiated” Black(?!) artistic thrusts are all distinguished by either a lessening or an eradication of the BAM ideological triad. Especially with the blaxploitation films, the directors as well as the producers of establishment “Blackness” were often Whites. The development of a Black aesthetic was mooted in favor of a return to “craft” and “standards” (code words for the readopting of traditional Euro-centric aesthetical concerns) or in favor of an emphasis on entertainment. Needless to say, social engagement was downplayed or entirely eliminated. Time and time again this central antagonistic dialectic is introduced by the establishment as a means of regaining control of Black artistic activity. Without an understanding of both the central internal and external dialectics which were put into play during the sixties and seventies, BAM’s achievements as well as BAM’s losses can not be accurately assessed.

Other contradictions. Examples of other dialectics at work include the internal effort to control Black publishing and to resist cooption by the external establishment or by establishment oriented and/or establishment sponsored forces who were ostensibly “Black.” Internally, this dialectic is illustrated by the development of Black publications and presses, Black bookstores, and an attempt to develop a Black book distribution system. Externally, this dialectic is illustrated by two boycott efforts: 1. The Ed Spriggs led boycott of Clarence Major’s New Black Poetry anthology and 2. The boycott of Essence magazine early in its development. Both of these boycotts should be understood in context.

BAM was not a “skin game.” Just being biologically Black was not sufficient. The triad of concerns was the base criteria used as points of definition and focus. Thus, in 1968 Ed Spriggs wrote “ON THE ‘BOYCOTT’ black writers/white publishers: an alliance that boycotts black publishers” first published in The Journal of Black Poetry and later reprinted in Black Art Black Culture, a collection of articles from The Journal of Black Poetry. Spriggs raised a number of very important issues, issues which retain their relevance in the 1990s. I quote him at length.

what I want understood is this boycott thing, and it is necessary to deal with this, is that this did not come about due to a personal clash with Clarence Major. I mean it is not about C. Major the man, the poet, but the ideological stance that is him, a lot of other Black writers and until recently, myself. and another thing that needs clarification is that it aint about International Publishers per se, yeah, we dig where they at. along with a lot of other publishers in that same direction and Praeger, say, in the opposite…

I took a stand, boycott. it’s time for that. it grew out of a telephone conversation with c major. while we talked the necessity to take the stand crystallized. repeat: black writers are being exploited even when they’re talking abt black power thru the white press. i mean some cat’s total economics and prestige depend upon the white publishers–not that they want it that way. we can break that up if we want to. our publishers will never be able to break out of this system if the boost doesn’t come from the black writers. swamp our publishers with the level of material that we turn over to the white publishers and domestic and international distributiorships will be a reality before the present system crumbles. there are many levels of power. let’s move on up a little higher.

We already have black publishers (no matter how minor some are) who consistently work with us. are we ready for that? c. major wasn’t. even tho he had been published in dudley r’s Broadside press anthology (For Malcolm X) and in the Journal of Black Poetry. Journal of Black Poetry is printed and published by black people entirely. Jamerson printing company does the job for the Journal. julian richardson, owner of Success Printing company does the job for Black Dialogue. Richardson and Associates are publishing a reprint of the Philosophy and Opinions of Marcus Garvey in paper and hard covers. san francisco could become the black publishing capital of afro-america if we had our souls where our mouths are. a lot more could be said abt the way we could support black publishers and what kind of changes we wld have to go thru to initiate that support. but we need to think, talk and act on this right away quick. we can take up the challenge now. we need to. unless some of us are already too revolutionary to entertain this kind of thing. it’s still possible for us to get our cookies and help the black publishers get theirs too.

repeat. it’s abt discontinuing the freeze we have dealt out to black publishers by ignoring their existence. me? i’m nuttin on every thing directed to the mother country’s houses that shat shld and cld be published black. so i wont get a poem here or a piece there. my life could never depend on it anyway. of course there are a couple of things due to come out that i let go of before i saw the necessity for this stance. no matter. we’ve got to stop the contradiciton at the point that we become aware of them. black publishers are laying in the cut waiting for the righteous black writers. black writers can bail them out.

There are institutions to be built. we’re young and strong enough to build but we’ve gotta have the vision. we have the power. if you don’t believe it just ask dial, harpers, wm morrow, grove, merit, marzani and munsell or even international publishers. couldn’t julian richardson, dudley randall and lafayette jamerson get into some very heavy drama if they could get just a little play from our co-opted black writers? you know they could. holes in yr front because you choose not to. fatten up. writers. black. seeking new dimensions of power. talk to me baby. we been laying back too long. [Spriggs / “On The ‘Boycott’,” pages 11 and 13-14]

Today, there is not one major literary anthology widely used in Black Studies, Black literature, or related courses that is both edited by Blacks and published by a Black press. The absence of Black control of the presentation of Black literature is indicative of how completely the establishment view dominates the discourse about and the actual production of Black literature. Worse than the reality of this alien and often antagonistic domination, is the reality that most of us see no major contradiction in the fact that the overwhelming majority of Black literature is produced by non-Black publishing concerns.

In a similar vein, a capitalist, entertainment orientation for the arts is generally acceptable in the nineties. But during the BAM era Blackness was more than a skin game. Thus, Askia Muhammad Toure’s call for a boycott of Essence in protest of “firings” and of interim editor Gordon Parks’ hiring of whites as art director and graphic illustrators. Undoubtedly, this protest helped pushed Essence towards a pro-Black position much faster than the magazine may have moved on its own.

Recently, in New York, Sister Hattie Gossett, an outstanding Black editor, was fired by the management of a new magazine for “inefficiency”. (Sister Hattie had worked “efficiently” for a year and a half at Redbook, a national women’s magazine. She quit her job at Redbook to join Essence in order to work for Black people.) Hattie Gossett is well known for her uncompromising Black views. We suggest that this is the real reason for her firing. About two weeks later, the editor, Miss Ruth Ross, a Black professional sister quit Essence magazine over an alleged “breach of contract.” So Essence magazine is now without the services of the two Black women editors who were to help launch it.

When the word of Sister Hattie’s dismissal passed along the grapevine, Black writers began to withdraw their work from the magazine. … Blackhearts!! we urge you to BOYCOTT ESSENCE MAGAZINE THROUGHOUT THE COUNTRY, AS ANOTHER “GAME” BEING RUN ON BLACK PEOPLE BY SLICK NIGGAS HUSTLING “BLACKNESS” FOR PROFIT; AIDED BY AN UNCLE TOM EDITOR WHO HATES AND DESPISES BLACK CREATIVE ARTISTS [Toure / “Report On The “Essence” Magazine Affair,” page 108]

From the example of these two boycotts, we can clearly discern that BAM was more than a simple reversal of the racist notion that if you’re white you’re right and if you’re black you’re wrong. BAM understood that unity around biological Blackness was not sufficient to advance BAM’s specific ideological goals.

Two other major dialectics at work were around 1. the question of integration, specifically inter-racial marriages, and 2. “the woman’s question.” BAM proponents were opposed to inter-racial marriages and were slow to respond to “feminism” which was viewed as a “middle-class, White woman’s thing.” The non-resolution of these contradictions led to splits between BAM and high profile integrationist-oriented Blacks and also to splits between BAM and Black women who prioritized politicality on gender issues. Alienated from BAM, many of these forces either forged new fronts of activity or joined existing establishment activities.

On this note, there is an interesting development. A number of high profile, male BAM spokespeople previously had been involved in inter-racial relationships. When they became BAM advocates they took an extremely hard line on inter-racial relationships. I postulate that they were inclined toward the hard line because as men they generally did not have the day to day responsibility of rearing the children produced from the interracial unions. LeRoi Jones is, perhaps, archetypal in this regard.

On the other hand, Black women who had been parties in inter-racial relationships and who had responsibility for rearing the children of those unions, did not take such a hard line. Alice Walker is an example of this. Undoubtedly, the Black male “holier-than-thou” hard-line alienated a significant number of important participants and potential participants.

The splitting of marriages and organizations based on race was a particularly painful development for a number of people who were veterans of the Civil Rights movement. Some of these veterans had made tremendous personal and political commitments to actualize integrated relationships. The advent of BAM strained many of those relationships to the breaking point. This strain accounts for some of the anti-BAM animosity which often manifests itself when BAM is accused of being “racist” or “crow-jim.” While I do not intend to blow this contradiction out of proportion, at the same time I do not intend to overlook the racial split and the hard feelings that resulted. Some of those feelings are still being worked out by people who were “negatively” affected.

The “race” contradiction was not just a personal issue. This contradiction was most violently played out in the conflicts between SNCC and the Panthers, and between the Panthers and so-called “cultural nationalists.” In relation to SNCC, the Panther position was that Panthers could work with anyone and that they had no hang-ups with Whites because they had never been controlled by Whites nor had Whites been leading members, whereas the Panthers believed that SNCC was obsessed with excluding Whites because Whites had once played dominant roles in SNCC. This, as well as the Panther antagonistic position on “cultural nationalists,” involved a great deal of exaggeration and some outright falsification. In relation to BAM, however, this produced another point of alienation.

After initially working together, BAM and the Panthers split forces in the late sixties. Emory Douglas, who was the Panther Minister of Culture, and, to a lesser extent Eldridge Cleaver, were both involved in early West Coast BAM activity. Emory did the cover for Sonia Sanchez’s book of poetry, Homecoming, and also contributed artwork to The Journal of Black Poetry. However, once the split intensified, Emory was directed by the Black Panther Party not to participate in any BAM activities. In hindsight, we can easily see that this was a self-destructive schism, but at the time the split played itself out as a major ideological battle.

Thus, the dialectic of assertion/alienation, i.e. the militant assertion of a political position alienates those who do not share that position. When the position in question has both personal and social implications in terms of mates, friends and associates, invariably what starts out as an ideological debate quickly degenerates into backbiting, infighting and self-destructive activities. Given its radical departure from the then existing norms, we should not be surprised that BAM was in constant internal turmoil as well as sometimes mired in “bickering and backbiting” centered around many prominent members of the more status-quo oriented artistic and political Black community.

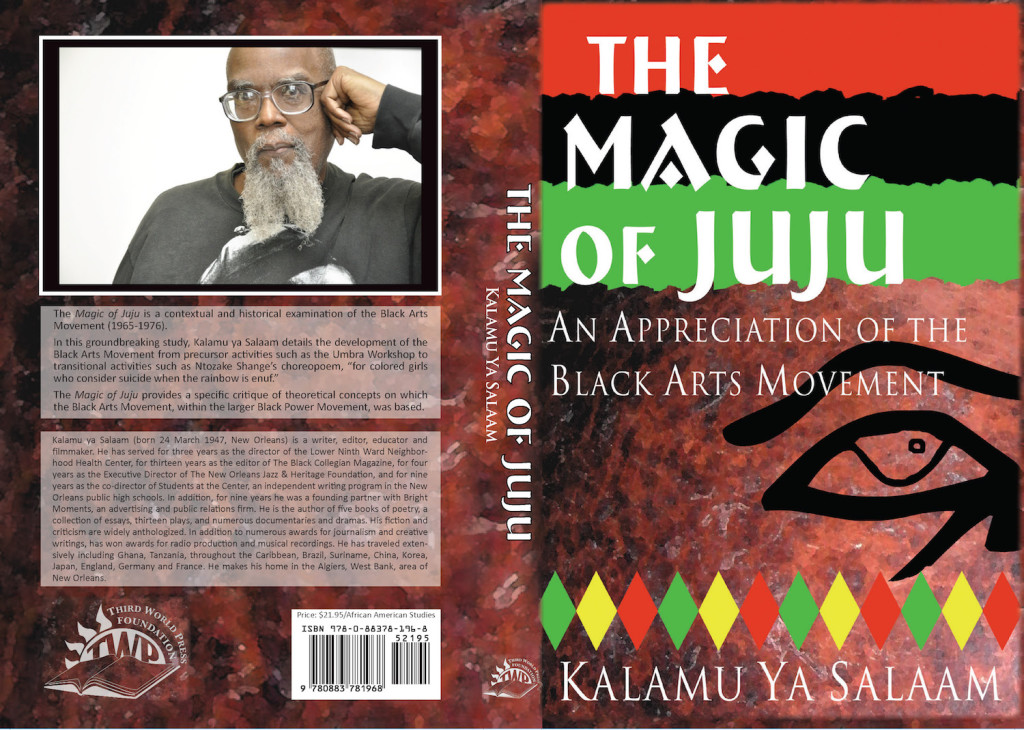

—Kalamu ya Salaam