Black Kos, Tuesday’s Chile

Tuesday Oct 25, 2016

Thomas Morris Chester (1834-1892), the first African-American war correspondent of a major daily newspaper, The Philadelphia Press

In American history, there is an unmistakable correlation between times of war, on one hand, and protests for and the eventual advancement of black civil rights, on the other. It is, after all, morally obscene for a nation to ask an individual or a group of people to “fight for the nation” while, at the same time, denying those very same people the rights and dignity that other citizens of that nation enjoy.

The dual and, at times, maddening reportage of black journalists on the nation’s wars while others, at home and abroad, were fighting for civil equality and dignity is, possibly, the great theme of African-American journalism. That social tension, palpable in much of the war reporting that I have read in the black press, produced some of the greatest reportage that I have ever read.

I am still in the process of researching for a future post here on African-American journalism during the nation’s wars. But the journalism of Thomas Morris Chester, the first African American war correspondent of a major daily newspaper deserves special mention.

As a part of the riveting New York Times series on the Civil War, Disunion, publisher jean Auets wrote of the fascinating story of Thomas Morris Chester, titled “A Black Correspondent at the Front“

Chester was born in Harrisburg, Penn., in 1834, the son of two black abolition activists. His mother, Jane, had escaped slavery in 1825; his father, George, was probably born a free man. They sold the abolitionist newspaper The Liberator at their restaurant, and may have hosted a stop on the Underground Railroad. Their community was tough, close-knit and prosperous. The citizens resisted, sometimes violently, slave-catchers who ventured there. When Frederick Douglass was pelted and beaten at a local public meeting, they enlisted friendly whites to help set up an-other meeting.

Edifying and reforming institutions, like churches, schools, fraternal lodges, benevolent societies and temperance and literary associations, permeated Chester’s early life and instilled in him a life-long belief in education. When he was 16 years old he attended Akron College, an African-American academy in Pittsburgh – a “fountain of learning,” he said. Later he attended school in New England and Liberia, and, after the Civil War, he graduated from the Inns at Court in London and was admitted to the bar.

This wealth of personal opportunities did not blind Chester to the realities of black life, North and South. In 1838, Pennsylvania changed its constitution to restrict the vote to “white freemen,” removing the franchise from “every freeman.” (Women did not enjoy voting rights, regardless of race or economic status.) The Fugitive Slave Law of 1850 scarred black communities nationwide as thousands of men, women and children fled to Canada to avoid capture.

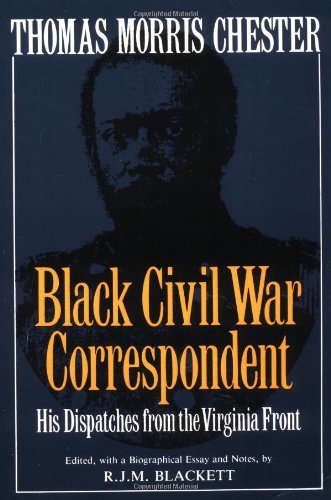

Chester’s Civil War correspondence for the Philadelphia Press was collected in a 1991 volume edited by Indiana University professor R.J.M. Blackett, titled Thomas Morris Chester, Black Civil War Correspondent: His Dispatches from the Virginia Front

A generous preview of the book is available at Google Books.

Chester’s prose reads as very typical of the 19th century. As Chester had been a Union soldier prior to his work with the Philadelphia Press, his personal moral outrage at the treatment of black Union soldiers is to be expected; that it was published in the “MSM” of its time, even given the moral certitude of the Union cause in the North, is extraordinary. In the excerpt I have chosen here, Chester maintains that even some in the Union did not have the right to climb on a moral high horse.

“It seems that the disposition to treat colored persons as if they were human is hard for even some loyal men to acquire. The wrongs which they have suffered in this department would, if ventilated, exhibit a disgraceful depth of depravity, practiced by dishonest men, in the name of Government. These poor people are not only plundered and robbed, but are kicked and cuffed by those who have robbed them of their hard earnings and sent them to other parts of their department, confident that their ignorance would be a guard against discovery…Among the colored troops are many laborers who are employed by the Government, and because they cannot continue their work like their soldier brethren, when shells are falling and exploding among them, this gallant Kentucky major amuses himself by tying up these redeemed freemen. It is generally believed that his success in this great canal enterprise will be a brigadier general’s commission of colored troops. This, to be as mild as possible, would be exceedingly unfortunate, and unjust to those who are making so many sacrifices for the perpetuation of The Union. Gen. Butler by no means allows any man, black or white, to be treated in such an unwarrantable manner.”

Thomas Morris Chester, Black Civil War Correspondent: His Dispatches from the Virginia Front pp. 137-38

You can read at the Auets NY Times piece that Chester was so much more than a war correspondent (in fact, he was the first African American man admitted to the bar in England).

It is notable, though, that even (and especially!) in a major daily (and mainstream) newspaper of the Civil War era, a black journalist were making the moral case for the dignity and autonomy of African Americans.; words which continue to be applicable to the present day.

>via: http://www.dailykos.com/stories/2016/10/25/1585736/-Black-Kos-Tuesday-s-Chile