RENÉ DEPESTRE

AND “POPA SINGER”:

HELLO AND

GOOD-BYE TO HAITI

In “René Depestre, bonjour et adieu à Haïti,” Tirthankar Chanda interviews Haitian author René Depestre, who speaks about his new book Popa Singer (Paris, Editions Zulma, 2016, 160 pages). Here is my translation of excerpts of Chanda’s interview:

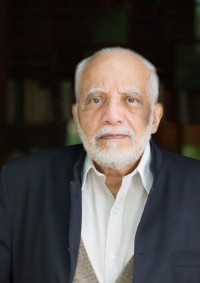

The Haitian great poet and novelist René Depestre, who has never stopped writing since the age of twenty, returned at the beginning of 2016 with a new book. Popa Singer is an autobiographical chronicle in which the writer depicts his return to Haiti in the 1950s, when the Duvalier regime was in place. The novel tells the story [. . .] of an essential page in Haitian history. Born in 1926 in Jacmel, Depestre is a surrealist novelist in the tradition of André Breton. In the pages of his new account, which combines fantasy and social satire, the tyrant Duvalier, alias Papa Doc, cohabits with the gods of Vodou and a Haitian matriarch determined to protect her children against the cruelties of the dictator. Mother-medium, possessed by the spirit of a German merchant living in Haiti, she fights the minions of the regime with bare hands.

RFI: Despite your age, you still want to write?

René Depestre: More than ever! I’m afraid I do not have enough time to finish all my current writing projects. I regret having been imprudent in pushing deadlines, and now here I am overtaken by old age. I have in mind a dozen book projects, including three novels, and several essays, but I will not write poetry, because poetry demands a lot more work than prose.

[. . .] Why have you set your new book in the past, in those fateful years of triumphant négritude?

In fact, I wrote it several years ago, but for lack of a suitable editor, the book remained confined in the darkness of my drawer. It was rediscovered by a literary critic friend. She put me in touch with the Zulma publisher, who thought it merited publishing. Suddenly, I found the confidence in myself and my literary creativity picked up again.

Yes, there is a lot of me and my family in it. This is the chronicle of my return to Haiti in December 1957, after over ten years of wandering around the world. I stayed at home for a whole year, before leaving again in 1959, this time to Cuba. It was a particularly bitter stay. It could not have been otherwise because of the dictatorship that was raging at the time in Haiti.

It is the time of Duvalier senior. Do you personally know the one ironically dubbed “Papa Doc?” Under what circumstances did you first know this sinister character?

I had known Doc Duvalier in the 1940s when I was still living in the country. He was my neighbor. At the time, he was a rather inconspicuous man. I even played cards with him. They called him “Doc” because he was a doctor specializing in tropical diseases. On my return in 1957, when I went to see him—he had sent his personal Cadillac to fetch me—I found a totally different man. He had become the bloody dictator we know. Haitians were afraid of him. I never imagined that a man could change so radically. My confrontation with the dictator and his guards is the central theme around which my new novel is constructed.

Why was Papa Doc angry with you?

He was mad at me because I had not responded to his invitation to dinner at his palace. I had also refused the post at the Ministry of Cultural Affairs that he had offered me. He asked me to implement, on the cultural front, his grand theory of ethnic cleansing on the island! When he developed his fascist-oriented program, my hair stood on end. Of course, I refused. But we do not say “No” to a bully with impunity. He took my refusal as an affront. He sent the Tonton Macoutes after me in the middle of the night to intimidate me and placed me under house arrest.

Your description of the nocturnal visit of the tyrant’s underlings, rummaging through your library looking for “suspicious” books, in your words, is an amazing story. Did the visit happen as you recount it?

Almost to a T! It would have been laughable had not the tension been so high, with the fear of being shot at every moment. I still see the head Macoute pointing his Colt 45 at back of my mother’s neck. Mother was not afraid. She told me the next day that she had seriously thought of slapping the guy. They wanted to see my library, especially since they thought they would find incriminating evidence of my communist “decadence.” As I had returned to Haiti with hopes of staying there, I did send by ship a collection of over 5000 books that I had gathered through my travels. The Tonton Macoutes had a field day. They confiscated a hundred books including The Little Prince and Little Red Riding Hood! Can you imagine? They called it the cleaning of my Bolshevik stable!

Your story is illuminated by the figure of your mother. Why is she called Popa Singer?

When we were children, we used to call our mother familiarly as “Popa,” but because she was inseparable from her sewing machine, we sometimes called her Popa Singer. She was the nurturing mother in all respects. She became a young widow and depended on her Singer machine to feed and raise her five children. She leaned night and day over her sewing machine; its mechanical rhythms punctuated my little boy dreams.

Popa also had another characteristic. . .

My mom was known for her states of possession. They said she was possessed by the “loa,” which is a Vodou deity. The loa who “rode” my mother was a white man. It was the spirit of a German trader who had fled Germany and took refuge in Haiti under the name of a famous Austrian poet, von Hoffsmanthal. So when mom was possessed by the spirit of her German loa, she became “Popa Singer von Hoffsmanthal.” All very surreal, but remember, we were in Haiti. André Breton—who came to the island in 1945, and who I had the opportunity of accompanying to a Vodou ceremony—said that Vodou was a popular form of Surrealism. This dreamlike religion constitutes the backdrop of life in Haiti.

Is today’s Haiti different from the country you experienced in the 1950s?

For two hundred years, Haiti has never stopped dying. I expected a resurrection after the 2010 earthquake, because it was not just an earthquake, but rather a quake of history. Afterwards, there was no resurgence of civil society as I had expected. Reconstruction will not be enough. My country needs to be re-founded.

>via: https://repeatingislands.com/2016/02/27/rene-depestre-and-popa-singer-hello-and-good-bye-to-haiti/