History of the

African American

repatriation movements

to Liberia, Sierra Leon,

and Haiti.

BY DOPPER0189, BLACK KOS MANAGING EDITOR

The ACS or the American Colonization Society (later renamed The Society for the Colonization of Free Colored People of America), was established in 1816 by Robert Finley of New Jersey. This organization was the primary vehicle for supporting the return of free African Americans to what was considered greater freedom in Africa.

Among other things it helped to found the colony of Liberia in 1821–22 as a place for freedmen (American blacks who were not slaves). Among its prominent supporters were Charles Fenton Mercer, Henry Clay, John Randolph, and Richard Bland Lee. Paul Cuffee, (1759 – 1817) a Quaker businessman, sea captain, patriot, and abolitionist, was an early advocate of settling freed blacks in Africa. He gained support from black leaders and members of the US Congress for an emigration plan that became known as repatriation.

In 1811 and 1815–16, Paul Cuffee financed and captained several successful voyages to British-ruled Sierra Leone, where he helped African-American immigrants get established. Although Cuffee died in 1817, his efforts may have inspired the American Colonization Society (ACS) to initiate further settlements. The ACS was a coalition made up mostly of evangelicals and Quakers, who supported abolition and Chesapeake slaveholders who understood that unfree labor did not constitute the economic future of the nation. They found common ground in support of so-called “repatriation”. They believed blacks would face better chances for full lives in Africa than in the U.S. The slaveholders opposed state or federally-mandated abolition, but saw repatriation as a way to remove free blacks and avoid slave rebellions.

From 1821, thousands of free black Americans moved to Liberia from the United States. Over twenty years, the colony continued to grow and establish economic stability. In 1847, the legislature of Liberia declared the nation an independent state. Critics have said the ACS was a racist society, while others point to its benevolent origins and later takeover by men with visions of an American empire in Africa. The Society closely controlled the development of Liberia until its declaration of independence. By 1867, the ACS had assisted in the movement of more than 13,000 black Americans to Liberia. From 1825 to 1919, it published the African Repository and Colonial Journal. After 1919, the society had essentially ended, but it did not formally dissolve until 1964, when it transferred its papers to the Library of Congress.

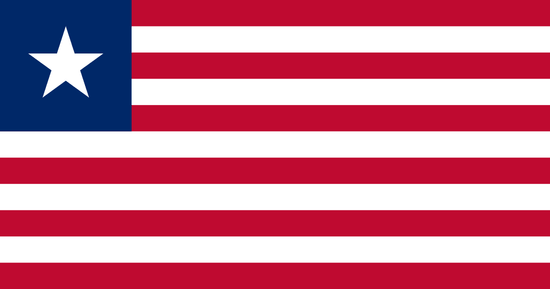

The Liberian constitution and flag were modeled after those of the United States. On January 3, 1848 Joseph Jenkins Roberts, a wealthy, free-born black American from Virginia who settled in Liberia, was elected as Liberia’s first president after the people proclaimed independence. Liberia is the only African republic to have self-proclaimed independence without gaining independence through revolt from any other nation (Ethiopia also remained independent but was an empire). Liberia is Africa’s first and oldest republic. Liberia maintained and kept its independence during the European colonial era. Today Americo-Liberians, who are descendants of African American and mostly Barbadian settlers, make up 2.5%. Congo people, descendants of repatriated Congo and Afro-Caribbean slaves who arrived in 1825, make up an additional estimated 2.5%.

The colonization effort resulted from a mixture of motives. Free blacks, freedmen, and their

descendants, encountered widespread discrimination in the United States of the early-19th century. Whites generally perceived black freedmen as both a social burden on society and a threat to white workers because they undercut wages. Some abolitionists believed that blacks could never achieve full equality in the United States and would be better off living Africa. Many slaveholders were worried that the presence of free blacks would encourage slaves to rebel.

Despite being antislavery, some Society members were openly racist and frequently argued that free blacks would be unable to assimilate into the white society of America. John Randolph, a famous slave owner, called free blacks “promoters of mischief.” At this time, about 2 million African Americans lived in America of which 200,000 were free persons of color (with legislated limits).

Henry Clay, a congressman from Kentucky who was critical of the negative impact slavery had on the southern economy, saw the movement of blacks as being preferable to emancipation in America, believing that “unconquerable prejudice resulting from their color, they never could amalgamate with the free whites of this country. It was desirable, therefore, as it respected them, and the residue of the population of the country, to drain them off”. Clay argued that because blacks could never be fully integrated into U.S. society due to “unconquerable prejudice” by white Americans, it would be better for them to emigrate to Africa.

Mean while the reverend Finley suggested at the inaugural meeting of an African Society that a colony be established in Africa to take free people of color, most of whom had been born free, away from the United States. Finley meant to colonize “(with their consent) the free people of color residing in our country, in Africa, or such other place as Congress may deem most expedient.”

Thus the organization, the Society for the Colonization of Free Colored People of America, quickly established branches throughout the United States., and was instrumental in the establishment of the colony of Liberia.

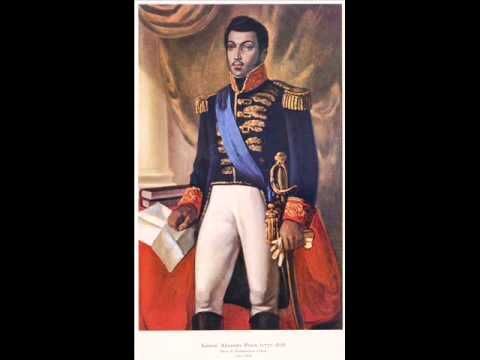

But the black repatriation movement wasn’t restricted just to trying to return free blacks to Africa. After the Haitian Revolution in the early 19th century, the leaders of Haiti had the opportunity to reshape the country’s identity. One of the early leaders of Haiti after the revolution, President Jean Pierre Boyer, envisioned a country that was welcoming to all of those of African descent. He promoted brotherhood, equality and citizenship to those who immigrated to Haiti. Furthermore, he believed that bringing free Africans together in Haiti would stimulate the country’s economy by increasing the labor force and strengthen diplomatic relations with the United States.

In 1824, President Boyer offered several incentives to encourage free African Americans to immigrate to Haiti, such as a free passage, land grants and financial support upon arrival. By August of 1824, several African Americans accepted President Boyer’s offer and were preparing to move to Haiti.

One of the largest groups left from Philadelphia and settled in the town of Samaná, which is now part of the Dominican Republic. Haiti and the Dominican Republic are on the same Caribbean island of Hispaniola, and at the time were on nation, as Haiti troops liberated the Dominican Republic from Spain (although the Dominican Republic later became its own nation).

Jonathas Granville and the Reverand Loring D. Dewey were two of the main proponents of African Americans immigrating to Haiti. Dewey was a member of the American Colonization Society, a group whose primary goal was to facilitate the return of free African Americans to Africa. The Rev. Robert Finley, a Presbyterian minister, had formed the society in 1816 based on his belief that Africans would never be fully integrated into the U.S. and were a threat to the nation’s well-being. He believed returning to Africa was the best option for them. Although as a result of the work of the ACS, more than 12,000 African Americans immigrated to Liberia, it became increasingly logistically difficult to send the emigrants to West Africa because the trip was longer and more expensive.

When the Reverand Dewey heard of President Boyer’s plans to repopulate Haiti, he began correspondences with Boyer. From this effort, Dewey coordinated the immigration of African Americans to Haiti in 10 locations on the island (including Samaná).

Jonathas Granville was a Haitian-born black living in the US. He was sent on behalf of Boyer to recruit more African Americans to immigrate to Haiti. In June of 1824, he traveled first to Philadelphia, and then to New York, where he distributed some of the money allotted by President Boyer to pay passage to Haiti. The Rev. Dewey and others wrote extensively in newspapers regarding the status and quality of life of those who immigrated to Samaná. In March of 1835, the North Star in Danville, Vt., reported, “The government appears to have realized every promise made by Mr. Grenville and about 270 of the immigrants are located at Samaná, where land has been given to them, on which some are already at work to improve, and are much encouraged to be industrious.”

After the end of the US Civil War and emancipation the political energy and financial support for repatriation quickly faded. But the back-to-Africa movement revived again in 1877 as Reconstruction ended. Many African Americans especially in the American South faced extreme violence and acts of terrorism from groups such as the Ku Klux Klan. Interest among the South’s black population in African repatriation noticeably peaked during the 1890’s, the same time period when racial terrorism reached its peak in the US. This was the same period when the greatest number of lynchings in American history took place.

The continued experience of segregation and discrimination of African Americans after emancipation, and the belief that they would never achieve true equality, attracted many of them to a Pan-African emancipation in their motherland.

But soon after this second boom, the movement again declined. Many high profile hoaxes and reported fraudulent activities began to be associated with the movement. But According to many historian, the most important reason for the decline in the back-to-Africa movement was that the “vast majority of those who were meant to colonize did not wish to leave the US. Most free blacks simply did not want to go “home” to a place from which they were now generations removed. America, not Africa, was their home and they had little desire to migrate to a strange and forbidding land not their own.”

The last peak of African American repatriation fever gained steam about 30 years later. The disillusionment of blacks who migrated to the North and frustrations of struggling to cope with urban life set the scene for the back-to-Africa movement of the 1920s. Blacks who fled North only to find similar levels of racism became attracted to an organization established by the Jamaican born Marcus Garvey, Blacks who migrated to the Northern States from the South and found that although they were financially better off, remained at the bottom both economically and socially, formed the bedrock of Garvey’s support the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA).

Garvey worked to develop a program to improve the conditions of ethnic Africans “at home and abroad” under UNIA auspices. On 17 August 1918, he began publishing the Negro World newspaper in New York, which was widely distributed. Garvey worked as an editor without pay until November 1920. He used Negro World as a platform for his views to encourage growth of the UNIA. By June 1919, the membership of the organization had grown to over two million, according to its records. Reasons behind this growth included the cultural revolution of the Harlem Renaissance, the large number of West Indians who immigrated to New York, and the appeal of the slogan “One God, One Aim, One Destiny,” to black veterans of the first World War.

On 27 June 1919, the UNIA set up its first business, incorporating the Black Star Line of Delaware, with Garvey as President. By September, it acquired its first ship. Much fanfare surrounded the inspection of the S.S. Yarmouth and its rechristening as the S.S. Frederick Douglass on 14 September 1919. Such a rapid accomplishment garnered attention from many. The Black Star Line also formed a fine winery, using grapes harvested only in Ethiopia. During the first year, the Black Star Line’s stock sales brought in $600,000. This caused it to be successful during that year. It had numerous problems during the next two years: mechanical breakdowns on its ships, what it said were incompetent workers, and poor record keeping. The officers were eventually accused of mail fraud.

The UNIA held an international convention in 1921 at New York City’s Madison Square Garden. Also represented at the convention were organizations such as the Universal Black Cross Nurses, the Black Eagle Flying Corps, and the Universal African Legion. Garvey attracted more than 50,000 people to the event and in his cause. The UNIA had 65,000 to 75,000 members paying dues to his support and funding.

They began advancing ideas to promote social, political, and economic freedom for black people. On July 2nd of that year, the East St. Louis riots broke out. A few days later on July 8th 1921, Garvey delivered an address, entitled “The Conspiracy of the East St. Louis Riots”, at Lafayette Hall in Harlem. During the speech, he declared the riot was “one of the bloodiest outrages against mankind”, condemning America’s claims to represent democracy when black people were victimized “for no other reason than they are black people seeking an industrial chance in a country that they have labored for three hundred years to make great”. It is “a time to lift one’s voice against the savagery of a people who claim to be the dispensers of democracy”. By October, rancor within the UNIA had begun to set in. A split occurred in the Harlem division, with Garvey enlisted to become its leader; although he technically held the same position in Jamaica.

Edwin P. Kilroe, Assistant District Attorney in the District Attorney’s office of the County of New York, began an investigation into the activities of the UNIA. He never filed charges against Garvey or other officers. After being called to Kilroe’s office numerous times for questioning, Garvey wrote an editorial on the assistant DA’s activities for the Negro World. Kilroe had Garvey arrested and indicted for criminal libel but dismissed the charges after Garvey published a retraction.

Garvey had also established the business, the Negro Factories Corporation. He planned to develop the businesses to manufacture every marketable commodity in every big U.S. industrial center, as well as in Central America, the West Indies, and Africa. Related endeavors included a grocery chain, restaurant, publishing house, and other businesses.

Convinced that black people should have a permanent homeland in Africa, Garvey sought to develop Liberia. It had been founded by the American Colonization Society in the 19th century as a colony to free blacks from the United States. Garvey launched the Liberia program in 1920, intended to build colleges, industrial plants, and railroads as part of an industrial base from which to operate. He abandoned the program in the mid-1920s after much opposition from European powers with interests in Liberia. In response to American suggestions that he wanted to take all ethnic Africans of the Diaspora back to Africa, he wrote, “We do not want all the Negroes in Africa. Some are no good here, and naturally will be no good there.”

Unfortunately Garvey’s success at raising capital, organizing blacks, and his plans had begone drawing unwarranted attention. In a memorandum dated 11 October 1919. Edgar Hoover of The Bureau of Investigation or BOI (after 1935, the Federal Bureau of Investigation), wrote to Special Agent Ridgely regarding Garvey: “Unfortunately, however, he [Garvey] has not as yet violated any federal law whereby he could be proceeded against on the grounds of being an undesirable alien, from the point of view of deportation.”

Sometime around November 1919, the BOI began an investigation into the activities of Garvey and the UNIA. Toward this end, the BOI hired James Edward Amos, Arthur Lowell Brent, Thomas Leon Jefferson, James Wormley Jones, and Earl E. Titus as its first five African-American agents. Although initial efforts by the BOI were to find grounds upon which to deport Garvey as “an undesirable alien”, a charge of mail fraud was brought against Garvey in connection with stock sales of the Black Star Line after the U.S. Post Office and the Attorney General joined the investigation.

The accusation centered on the fact that the corporation had not yet actually purchased the ship, which had appeared in a BSL brochure emblazoned with the name “Phyllis Wheatley” (after the African-American poet) on its bow. The prosecution stated that a ship pictured with that name had not actually been purchased by the BSL and still had the name “Orion” at the time; thus the misrepresentation of the ship as a BSL-owned vessel constituted fraud. The brochure had been produced in anticipation of the purchase of the ship, the organization had a preliminary contract to buy the ship, and appeared to be on the verge of completion at the time. None the less, “registration of the Phyllis Wheatley to the Black Star Line was thrown into abeyance as there were still some clauses in the contract that needed to be agreed.” In the end, the ship was never registered to the BSL.

When the trial ended on 23 June 1923, Garvey had been sentenced to five years in prison. Upon his release the US deported him to Great Britain. The UK which was also worried his support and international alliance with the then developing Rastafarian movement and their “Negus” (a mythical black king whose coming would free all black people) would eventually undermine British control of the Carribbean and West Africa. They thus worked to crush his organization. Under attack by both the US and UK government the UNIA quickly faded, destroying the last major American based African repatriation organization.

>via: http://www.dailykos.com/stories/2016/9/16/1570075/-Black-Kos-Week-In-Review