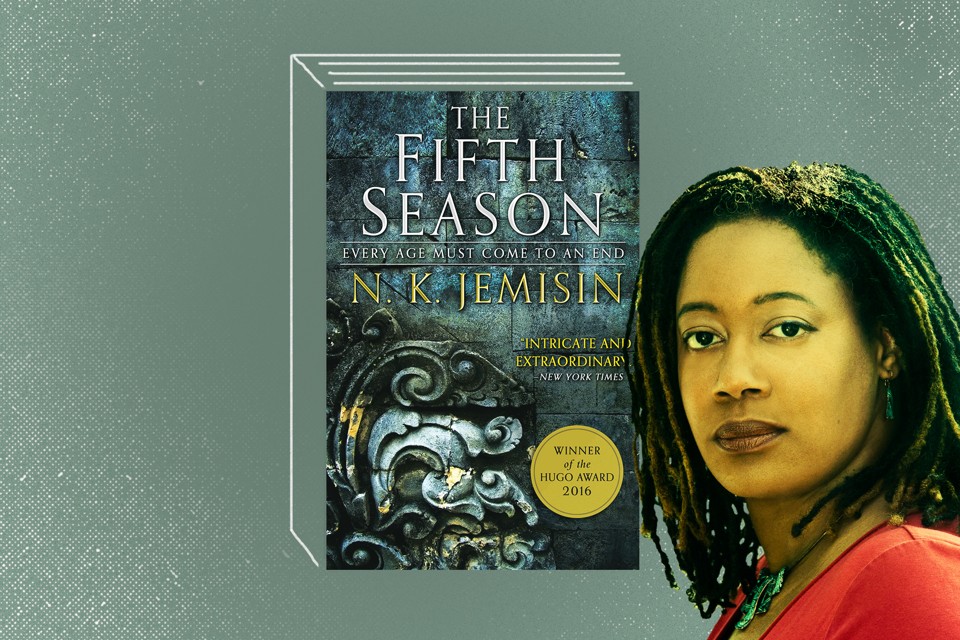

Jemisin the first black writer to win the Hugo Award for

Best Novel, perhaps the highest honor for science-fiction

and fantasy novels. Her winning work, The Fifth Season,

has also been nominated for the Nebula Award and World

Fantasy Award, and it joins Jemisin’s collection of feted

novels in the speculative fiction super-genre. Even among

the titans of black science-fiction and fantasy writers,

including the greats Octavia Butler and Samuel Delany,

Jemisin’s achievement is singular in the 60-plus years

of the Hugos.

work, and it accomplishes the one thing that is so difficult

in a field dominated by tropes: innovation, in spades. A

rich tale of earth-moving superhumans set in a dystopian

world of regular disasters, The Fifth Season manages to

incorporate the deep internal cosmologies, mythologies,

and complex magic systems that genre readers have come

to expect, in a framework that also asks thoroughly modern

questions about oppression, race, gender, class, and

sexuality. Its characters are a slate of people of different

colors and motivations who don’t often appear in a field

still dominated by white men and their protagonist avatars.

The Fifth Season’s sequel, 2016’s The Obelisk Gate,

continues its dive into magic, science, and the depths

of humanity.

the science-fiction norm as The Fifth Season winning the

Hugo Award seemed unlikely. In 2013, a small group of

science-fiction writers and commentators launched the

“Sad Puppies” and “Rabid Puppies” campaigns to exploit

the Hugo nomination system and place dozens of books

and stories of their own choosing up for awards. Those

campaigns arose as a reaction to perceived “politicization”

of the genre—often code for it becoming more diverse and

exploring more themes of social justice, race, and gender

—and became a space for some science-fiction and fantasy

communities to rail against “heavy handed message fic.”

Led by people like the “alt-right” commentator Vox Day,

the movements reached fever pitch in the 2015 Hugo

Award cycle, and Jemisin herself was often caught up in

the intense arguments about the future of the genre.

I spoke to Jemisin about her works, politics, the sad puppies

controversy, and about race and gender representation in

science-fiction and fantasy the day before The Fifth Season

won the Hugo Award. Our conversation has been edited for

length and clarity.

creative process that goes into this trilogy. This

seems like a huge undertaking.

done one continuous story all the way through three books.

Trilogies are relatively easy when each story is a self-

contained piece, which I’ve done for all of my previous

books. I have a lot of new respect for authors who do like

giant unending trilogies just because this is hard. It’s a lot

harder than I thought it was. But I’m enjoying it so far. It’s

a solid challenge. I like solid challenges. I had some

moments when I was writing the first book where I was

just sort of, “I don’t know if I can do this.” Fortunately I

have friends who are like, “What’s wrong with you? Snap

out of it!” And I moved on and I got it done and I’m very

glad with the reception. I’m shocked by the reception, but

I’m glad for it.

seems like something that is tailor-made to be a

hit right now.

been happening in the genre in terms of pushback,

reactionary movements and so forth. Basically, the

science-fiction microcosmic version of what’s been

happening on the large-scale political level and what’s

been happening in other fields like with Gamergate in

gaming. It’s the same sort of reactionary pushback that

is generally by a relatively small number of very loud

people. They’re loud enough that they’re able to

convince you that the world really isn’t as progressive

as you think it is, and that the world really does just

want old-school 1950s golden-age-era stalwart white

guys in space suits traveling in very phallic-looking

spaceships to planets with green women and … they

kind of convince you that that’s really all that will sell.

Told in the most plain didactic language you can

imagine and with no literary tricks whatever because

the readership just doesn’t want that.

Newkirk: For you, are those people something that bothers you as you build a profile? Are people louder now that The Fifth Season is getting so much love?

I seem to have passed some kind of threshold, and maybe

it’s something as simple as I now have so many positive

messages coming at me that the negatives are sort of

drowned out. As a side note, the so-called boogeyman of

science-fiction, the white supremacist asshat who started

the Rabid Puppies, Vox Day, apparently posted something

about me a few days ago and I just didn’t care. There was

a whole to-do between me and him a few years back where

he ended up getting booted out of SWFA [Science Fiction

and Fantasy Writers of America] because of some stuff he

said about me, and I just didn’t care. It was a watershed

moment at that point but now it’s just sort of, “Oh, it’s him

again. He must be needing to get some new readers or

trying to raise his profile again. Or something.” I didn’t

look at it. No one bothered to read it and dissect it and

send me anything about it. No one cared.I think that’s

sort of indicative of what’s happening. To some degree,

as I move outside of the exclusive genre audience, the

exclusive genre issues don’t bother me as much. Maybe

that’s just speculation. I’m reaching a point where I’m

still hearing some of it, but it’s just not as loud, or

maybe it’s just focusing on different points. I don’t

know. It’s still there. It’ll be there. I think that the

Hugo ceremony at this upcoming WorldCon is going

to be another not-as-seminal moment as last year

when the Puppies tried a takeover that was somewhat

more successful at the nominating stage and where

they got smacked down roundly at the actual voting

stage with no award after no award. I don’t think

that’s going to happen this year, and I don’t think it

matters as much. But who knows? I’ll guess we’ll

see. If I win I’ll be happy. If I don’t win, I’ll be happy.

I’ll continue to write.

a lot when it happened [his translation of

Cixin Liu’s The Three Body Problem won the

2015 Hugo Award for Best Novel], and he

said all that stuff sort of loses its power over

time, because it’s reactionary. It’s something

where the facts and your audience numbers

don’t really lie.

unless they find something new to catch and burn on.

And when they keep using the same tactics over and over

again, I don’t know that that’s sustainable. Or they’ll

burn themselves out when they reach the point of, I guess,

Donald Trumpism, for lack of a better description. They

reach some point where it’s no longer a reactionary

movement, some demagogue tries to take the lead and

make it all about them. And at that point it becomes clear

that it’s just some kind of petty narcissistic thing, and I

think that’s what kills it. But we’ll see, both at the Hugos

level and in the polls in November.

Newkirk: There are some very strong allegories in

both books and they also play alongside an actual

effort to build in racial critiques in a fantasy world.

It’s weird to me how uncommon that is in a lot of

people’s perspectives about science-fiction and

fantasy. How do you pull that off?

Jemisin: I write what feels real. I write things that are informed both by my own experience and by actual history. And I’m not drawing solely upon my own racial experiences. There’s some stuff that’s going to happen in the third book that’s sort of hinting at the Holocaust. You can see hints of stuff that happened with the Khmer Rouge at varying points in the story. You see the ways in which oppression perpetuates itself, one group of people teaches every other group of people how to do truly horrible things. I was drawing in that case on King Leopold of Belgium’s horrible treatment of people in the Congo—chopping off hands for example—and how in the Rwandan Civil War they chopped off lots of hands. Well, they learned it from the Europeans.

like pretty other kid in America. Sort of half-asleep through

history, memorizing facts so that I could spit them back and

take the AP exam, and that was not fun. But then later on, as I

got older and I actually started reading this stuff from different

perspectives and started considering different research

methods, and as I started to realize just how much I’d learned

in school was just bullshit, then it became a lot more

interesting to me. So as I read about the different sets of

people who have been oppressed and the different systemic

oppressions that have existed throughout history, you start

to see the patterns in them. Obviously I’m drawing on my

own African American experience, but I’m drawing on a lot

of other stuff too.

oppression is really driven home in The Fifth Season.

to me within the boundaries of science-fiction and fantasy.

They really are supposed to be about people. It’s fiction. It’s

not a textbook, yet for decades, for reasons that I don’t fully

understand, there was this weird aversion to good sociology

and focusing on good characterization and people acting like

real people. It was all supposed to be about the science. And

so you would go into forums, and you would see dozens of

people nitpicking the hell out of the physics. “The equipment

doesn’t work this way!” Just engineering discussions out the

wazoo, but no one pointing out, “You know, your characters

are completely unrealistic. People don’t act this way. People

don’t talk this way. What is this?” I just feel like that doesn’t

make sense. Social sciences are sciences too, and that

aversion to respecting the fiction part of science-fiction; to

exploring the people as well as the gadgets and the science

never made sense to me. And that aversion is why it isn’t

common to see these kinds of explorations of what people

are really like and how people really dominate each other,

and how power works.

were writing these stories were people who didn’t have a good

understanding of their own power: their own privilege within

a system, and a kyriarchical system, and not understanding

that as mostly straight white men with a smattering of other

groups who are writing this genre for years. A lot of them

bought into the American ideal of rugged individualism of,

“Go forth intrepid person with their gun,” and they would go

forth and do brave things and that would bring them power.

No recognition of the power they already had. And I think it

does take an outsider to a degree to come in and look around

and read the stuff that’s key in the genre and be like, whoa

something is really missing here.But I don’t think that I was

the first outsider to do so by any stretch. Most of the writers

of color who have come into the genre have come and looked

around and had that moment. Of course, Octavia Butler

being the first and foremost who came in and looked at the

alien colonization story and said, “Oh, hey it’s a lot like what

happened to [black people]! Why don’t we just make all that

stuff explicit? Instead of rape, why don’t we include aliens

trying to assimilate our genes?” And it does take people who

understand systems of power, who understand the

complexities of how people interact with each other to

depict that.

>via: http://www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2016/09/nk-jemisin-hugo-award-conversation/498497/