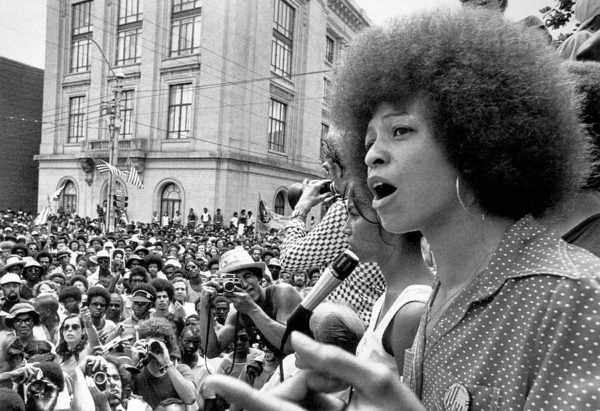

My afro

isn’t superficial

— it’s political

Not since the civil rights movement has the afro been so visible, but now its purpose isn’t just political — it’s aesthetic. Designers now use “natural” models regularly, countless black-owned online stores and care sites have sprouted up, and even mainstream cosmetic brands have developed product ranges catered to kinks and coils. For me, however, the journey to my afro definitely was political. It was also deeply personal and a way to solidify and explore my identity as someone with black heritage.

I grew up in a small village on the south coast of England, where I was the only mixed girl and one of only three black people in my school. Despite not having a white parent, I was born with a form of partial albinism, which gave me white skin and green eyes. The only “black” feature that remained was a wild kinky mass of hair atop my head that set me apart from everyone and made me a perfect target for racial bullying. I was beaten up and had gum put in my hair on buses — but it wasn’t just students who were doing the bullying. My head of year (i.e. the teacher responsible for my grade), Miss Fearon, referred to me as “you with the hair” until my parents complained. My other year leader, Miss Ellard, called me into her office one day to yell at me about daring to wear a “provocative” hairstyle to school. I experienced this kind of treatment literally every day until the age of 16, when I left school and my mother allowed me something I’d wanted since I was a little girl, that every other adult woman on her side had: a chemical relaxer.

Relaxers are strong, alkaline chemicals that soften the structure of the kinky hair shaft, permanently straightening strands and allowing submission into Caucasian styling and ease of brushing. What no one tells you is that the process causes damage and breakage, chemical burns on the scalp, and requires top-ups every three months to keep the roots from looking odd. But I didn’t care, I smiled at myself in the mirror — the smile widening when my stylist told me I’d look just like Beyoncé when she was done. Not for the first time, I bit my lip and squirmed in the seat, trying not to think about the burning sensation creeping across my scalp.

And there it is. How many celebrated black women in the mainstream have their natural kinks and curls on display? Since colonialism and slavery, “nappy” has been used as an insult, and slaves used anything they could to flatten their hair — from butter to kerosene. Upon their separation from their tribes, hair practices like intricate threading, braids, and tools were lost and the concept of “good” and “bad” hair was formed. The dominant, Eurocentric beauty standard reigned supreme and black women spent billions trying to achieve it. It still reigns. Again, think of “Queen Bey,” probably considered the most beautiful black woman in the world… Who is also never seen without her waist-length, straight, blonde wig. It’s no coincidence.

But I loved not standing out. I loved that men no longer stopped their cars to throw cans at me and scream about my hair, or corner me in doorways just to tell me how stupid I looked. I actually felt pretty for once, which made the scabby scalp and intense fear of rain (it’s hard to avoid the frizz in England!) all worth it. On top of the relaxer, I used my heated straighteners to fry my withered strands into bone-straight, brittle submission, so it always broke before it passed an inch past my shoulders. But who cared? I looked the way pretty girls looked.

After a couple of years working and not fitting in at college, I decided to fulfill a dream of mine and moved to Asia. By chance, I ended up in China. The experience was intense and exhausting but taught me a lot about myself and culture. I was a nanny to a wealthy family and during the school day I had the freedom to explore the city I lived in — Hangzhou — browsing stores with make-up departments that displayed huge blow-ups of artificially lightened models.

I was struck by the extent to which colourism affects Asia — something I hadn’t considered before living there. On the way back up to my floor in the apartment building my host family lived in, there was a poster advertising skin lightening, with painful-sounding procedures and ominous creams promising to give women with darker skin a face lightened by several shades. My initial reaction was scorn, thinking one would have to be very vain to consider that, but then I began to really look at myself in the mirror. How exactly was I working to dismantle the white beauty myth with this all of the tedious effort every day? I was just reinforcing it.

I left China some months later, as well as the boxes upon boxes of relaxer I’d squirreled away at the back of my closet in anticipation of a drought. I was done.

I relearned my hair, healthy practices, and products. I threw away my straighteners and my blow dryer and began to transition, fear and excitement growing with every fresh, curly inch. I moved to Mexico where I worked full-time as a freelance writer, and from there followed a friend to Los Angeles, where I found a creative environment full of incredible looking, inspirational black women, rocking their hair on the street, and a boyfriend who adored my hair, for once. After a year, my hair was a half and half mess of relaxed and curly, so he offered to cut it off for me. As each tress was trimmed, my hair sprung outward with life, framing my head like a halo. As he brushed the loose hairs from my back, I burst into tears with shock. It took weeks to feel comfortable, but after adjusting I felt freer than I had in a long time.

White women might say “it’s only hair,” but the intense shaming women of colour are exposed to — both within and outside the community — around natural hair is staggering. Like many mixed people, I experienced some hostility from both sides, and was occasionally subjected to other types of slurs, this time from groups of black men seemingly put-out I was wearing my afro outside, as well as online, where the opinions I expressed in natural hair groups on social media were derided as coming from a “half-breed mongrel” with a “wig.” The afro also “exoticized” my look, and strangers in the street started touching my hair without asking, including a restaurant owner, who dug his hands deep into hair murmuring “beautiful, beautiful,” leaving me stunned, standing in the doorway of his restaurant.

Fast forward to today: It’s been years since I’ve used heat or permanent chemicals on my hair. I use black-owned, store-bought leave-in conditioner and mineral or coconut oil. My hair, now waist length when wet, has never been healthier. I’ve never felt better or more confident about the way I look.

Let me be clear, the state of a black woman’s hair has no bearing on her “blackness.” Black women might love the ease and the look of straighter hair, or need they might to keep it that way for professional reasons (employers discriminate massively — for a long time the US army, for example, disallowed certain braids that are essential to black women’s hair care), and that is up to them. But for me, my natural hair helped me embrace my identity and sow the seeds for me to learn more about black feminism and politics.

All I ask is that white women don’t use words like “nappy,” or “frizzy” as an insult. The next time you see Oprah or Beyonce wearing rocking their weave, ask yourself why that is, or give Chris Rock’s fantastic documentary, Good Hair, a watch.

It might seem superficial, but to me it’s political — it’s about throwing off the lingering colonialism that blights the lives of women of colour, making them feel second best. My hair is who I am.

+++++++++++

Soraya Heydari is a Black Anglo-Iranian writer, living in LA and working in the music industry.

>via: http://www.feministcurrent.com/2016/08/08/afro-isnt-superficial-political/