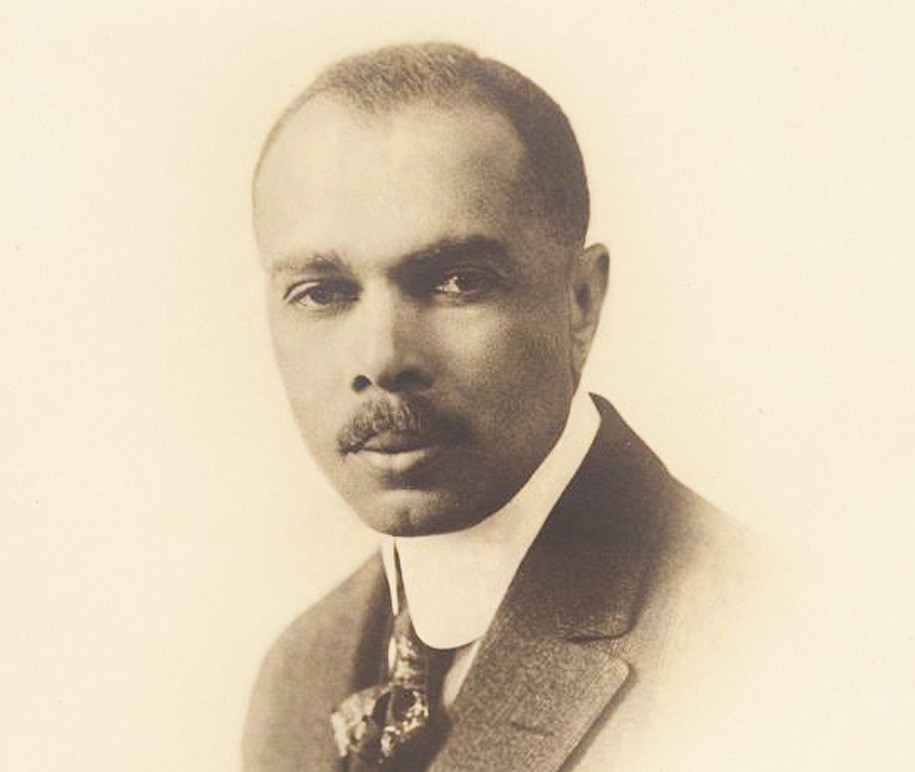

The month of June marks both the birth and death of a key black figure in American history: James Weldon Johnson. My first introduction to Johnson was through a song.

It was not until 1956 when my family moved from New York City to the campus of Southern University in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, a Historically Black College (HBCU), that I had the chance to sing what was then known as the “Negro National Anthem” in a school assembly.

Though I had heard it sung in church back north, I was the only child in that auditorium who didn’t know the words by heart. The other students, children of faculty and staff on campus, belted it out with fervor, and knew each stanza.

Lift Ev’ry Voice and Sing – often called “The Black National Anthem” – was written as a poem by James Weldon Johnson (1871-1938) and then set to music by his brother John Rosamond Johnson (1873-1954) in 1899. It was first performed in public in the Johnsons’ hometown of Jacksonville, Florida as part of a celebration of Lincoln’s Birthday on February 12, 1900 by a choir of 500 schoolchildren at the segregated Stanton School, where James Weldon Johnson was principal.

There is course no recording of that original performance in Jacksonville 116 years ago. Over the decades, it has been performed in schools and at national events by choirs, choruses, and music celebrities. Each generation incorporates new musical genres into the interpretation, yet the basic message remains the same: Hope rising up out pain and obstacles.

Groups like these young people in Nashville sing a song of passion and pride.

Here are the lyrics:

Lift ev’ry voice and sing, ‘Til earth and heaven ring, Ring with the harmonies of Liberty; Let our rejoicing rise High as the list’ning skies, Let it resound loud as the rolling sea. Sing a song full of the faith that the dark past has taught us, Sing a song full of the hope that the present has brought us; Facing the rising sun of our new day begun, Let us march on ’til victory is won.

Stony the road we trod, Bitter the chastening rod, Felt in the days when hope unborn had died; Yet with a steady beat, Have not our weary feet Come to the place for which our fathers sighed? We have come over a way that with tears has been watered, We have come, treading our path through the blood of the slaughtered, Out from the gloomy past, ‘Til now we stand at last Where the white gleam of our bright star is cast.

God of our weary years, God of our silent tears, Thou who has brought us thus far on the way; Thou who has by Thy might Led us into the light, Keep us forever in the path, we pray.

Lest our feet stray from the places, our God, where we met Thee, Lest, our hearts drunk with the wine of the world, we forget Thee; Shadowed beneath Thy hand, May we forever stand, True to our God, True to our native land.

Producer Deborah McDuffie’s video production above is a joy to watch.

In 1985 Miller High Life asked me to come up with a “meaningful” project for Black History Month. I decided to arrange and record a celebratory contemporary version of “Lift Every Voice and Sing”. I called good friends Al Green and Deniece Williams who agreed to sing the duet, backed by Patti Austin, Roberta Flack, Melba Moore and myself. The band consisted of the studio musicians who made up John Belushi and Dan Ackroyd’s Blues Brothers Band, along with other notable musicians, including the late great Yogi Horton and jazz legend Jon Faddis. One of my favorite arrangers, Leon Pendarvis penned the charts and was Musical Director. Husband and wife actors Ossie Davis and Ruby Dee provided the voice-over narration for the commercials. Recorded in New York at Clinton Studios, it started out as a jingle but ended up a full length recording.

This is the actual video from the recording session. Al was 8 hours late as usual, which is why it’s dark when he’s arriving. It’s a fun-filled sneak peek inside what goes on (or used to go on) in the recording studio. Enjoy!

So that is the anthem. But what of the man behind it?

Among his most famous works, The Autobiography of an Ex-Colored Man in many ways parallels Johnson’s own remarkable life. First published in 1912, the novel relates, through an anonymous narrator, events in the life of an American of mixed ethnicity whose exceptional abilities and ambiguous appearance allow him unusual social mobility — from the rural South to the urban North and eventually to Europe.

A radical departure from earlier books by black authors, this pioneering work not only probes the psychological aspects of “passing for white” but also examines the American caste and class system. The human drama is powerful and revealing — from the narrator’s persistent battles with personal demons to his firsthand observations of a Southern lynching and the mingling of races in New York’s bohemian atmosphere at the turn of the century.

Revolutionary for its time, the Autobiography remains both an unrivaled example of black expression and a major contribution to American literature.

Johnson also wrote God’s Trombones: Seven Negro Sermons in Verse.

God’s Trombones, in full God’s Trombones: Seven Negro Sermons in Verse, volume of poetry by James Weldon Johnson, published in 1927. The work represents what the author called an “art-governed expression” of the traditional black preaching style. The constituent poems are an introductory prayer, “Listen, Lord—A Prayer,” and seven verse sermons entitled “The Creation,” “The Prodigal Son,” “Go Down Death—A Funeral Sermon,” “Noah Built the Ark,” “The Crucifixion,” “Let My People Go,” and “The Judgment Day.” Although he identified himself as an agnostic, Johnson drew heavily throughout his career from the oral tradition and biblical poetry of his Christian upbringing. In God’s Trombones, he conveys the raw power of fire-and-brimstone oratory while avoiding the hackneyed devices of dialectal transcription that had marred much previous literature that attempted to reflect African American speech.

Here is the full text and illustrations.

Theater companies across the nation, like the Paul Robson Performing Arts Companyin Syracuse, New York, continue to produce and stage this classic:

It has also been interpreted musically, as seen below.

While Johnson was and is renowned for his literary contributions, he was equally important for his politics and activism. Often overlooked is his role as a diplomat. He spoke both French and Spanish fluently.

In 1906 Johnson was appointed by the Roosevelt Administration as consul of Puerto Cabello, Venezuela. In 1909, he transferred to Corinto, Nicaragua. During his stay at Corinto, a rebellion erupted against President Adolfo Diaz. Johnson proved an effective diplomat in such times of strain

He rose to major civil rights prominence via the NAACP.

In 1916, Johnson started working as a field secretary and organizer for the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), which had been founded in 1910. In this role, he built and revived local chapters. Opposing race riots in northern cities and the lynchings frequent in the South during and immediately after the end of World War I, Johnson engaged the NAACP in mass demonstrations. He organized a silent protest parade of more than 10,000 African Americans down New York City’s Fifth Avenue on July 28, 1917 to protest the still-frequent lynchings of blacks in the South.

Social tensions erupted after veterans returned from the First World War, and tried to find work. In 1919, Johnson coined the term “Red Summer” and organized peaceful protests against the white racial violence against blacks that broke out that year in numerous industrial cities of the North and Midwest. There was fierce competition for housing and jobs. Johnson traveled to Haiti to investigate conditions on the island, which had been occupied by U.S. Marines since 1915 because of political unrest. As a result of this trip, Johnson published a series of articles in The Nation in 1920 in which he described the American occupation as brutal. He offered suggestions for the economic and social development of Haiti. These articles were later collected and reprinted as a book under the title Self-Determining Haiti.

In 1920 Johnson was chosen as the first black executive secretary of the NAACP, effectively the operating officer position. He served in this role through 1930. He lobbied for the Dyer Anti-Lynching Bill of 1921, which was passed easily by the House, but repeatedly defeated by the white Southern bloc in the Senate. The Southern bloc was powerful because their state legislatures had effectively disfranchised most African-American voters around the turn of the century, but the states had retained the full congressional apportionment related to their total populations. Southern Democratic congressmen, running unopposed, established seniority in Congress and controlled important committees. Throughout the 1920s, Johnson supported and promoted the Harlem Renaissance, trying to help young black authors to get published. Shortly before his death in 1938, Johnson supported efforts by Ignatz Waghalter, a Polish-Jewish composer who had escaped the Nazis of Germany, to establish a classical orchestra of African-American musicians.

While he was consul, he married Grace Nail—an activist in her own right.

Grace Elizabeth Nail was born in New London, Connecticut, the daughter of real estate developer John Bennett Nail and his wife, Mary Frances Robinson. Her father was the first life member of the NAACP. Her brother was developer John E. Nail, head of the Harlem branch of the NAACP. Grace was raised in New York City.

Grace Nail Johnson is usually associated with the Harlem Renaissance. She was a hostess, mentor, and activist on behalf of civil rights causes. She was founder of the NAACP Junior League, organized in 1929. She was the only black member of Heterodoxy, a feminist group based in Greenwich Village. Nella Larsen recalled traveling with Grace Johnson in the South in 1932, and passing as white patrons at a restaurant in Tennessee, as a “stunt.” In 1941, Eleanor Roosevelt invited Mrs. Johnson to the White House along with Mary McLeod Bethune and Numa P. G. Adams, to discuss race relations.

During World War II Mrs. Johnson publicly resigned from a committee of the American Women’s Voluntary Services because of racial discrimination in their work projects. The following year she spoke on an NBC radio program about equal pay: “We should not have two wage scales for the same job–one for men and one for women, one for Negroes and one for whites.

During his tenure at the NAACP, Johnson maintained an interest in not only U.S. racial injustice, but also in conditions in Haiti. In 1920 he wrote “Self-Determining Haiti,” four articles reprinted from The Nation reporting an investigation made for the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. (The full text is at Project Gutenberg.)

The articles and documents in this pamphlet were printed in The Nation during the summer of 1920. They revealed for the first time to the world the nature of the United States’ imperialistic venture in Haiti. While, owing to the censorship, the full story of this fundamental departure from American traditions has not yet been told, it appears at the time of this writing, October, 1920, that “pitiless publicity” for our sandbagging of a friendly and inoffensive neighbor has been achieved. The report of Major-General George Barnett, commandant of the MarineCorps during the first four years of the Haitian occupation, just issued, strikingly confirms the facts set forth by The Nation and refutes the denials of administration officials and their newspaper apologists. It is in the hope that by spreading broadly the truth about what has happened in Haiti under five years of American occupation. The Nation may further contribute toward removing a dark blot from the American escutcheon, that this pamphlet is issued.

Johnson also took on a role in academia.

In 1930 at the age of 59, Johnson returned to education after his many years leading the NAACP. He accepted the Spence Chair of Creative Literature at Fisk University in Nashville, Tennessee. The university created the position for him, in recognition of his achievements as a poet, editor, and critic during the Harlem Renaissance. In addition to discussing literature, he lectured on a wide range of issues related to the lives and civil rights of black Americans. He held this position until his death. In 1934 he also was appointed as the first African-American professor at New York University, where he taught several classes in literature and culture.

His death was untimely:

Johnson died in 1938 when an automobile in which he was riding was struck by a train in rural Maine. More than 2000 mourners attended his Harlem funeral. He was buried in Brooklyn’s Greenwood Cemeteryholding a copy of God’s Trombones in his hands.

Over the years since his death, many schools and literary collections have been named in his honor, and he was also portrayed on a U.S. postage stamp as part of their Black Heritage Series. The Beinecke Library at Yale houses The James Weldon Johnson Memorial Collection of American Negro Arts and Letters:

The James Weldon Johnson Memorial Collection of American Negro Arts and Letters was founded in 1941 by Carl Van Vechten in honor of James Weldon Johnson (1871 – 1938). The collection celebrates the accomplishments of African American writers and artists, with a strong emphasis on those of the Harlem Renaissance. Grace Nail Johnson contributed her husband’s papers, leading the way for gifts from many of Johnson’s friends and colleagues. A writer, cultural critic, and photographer, Van Vechten was also a visionary collector. His donation of books, manuscripts, correspondence, photographs, and memorabilia as well as his ongoing advocacy for contributions from literary friends and fellow writers established the James Weldon Johnson Memorial Collection as one of the most significant archives documenting African American arts and letters.

Photographs from the collection were published in Generations in Black and White: Photographs from the James Weldon Johnson Memorial Collection.

This portfolio of eighty-three photographs constitutes a stunning celebration of African American achievement in the twentieth century. Carl Van Vechten, a longtime patron of black writers and artists, took these photographs over the course of three decades—primarily as gifts to his subjects, such luminaries as W. E. B. Du Bois, Langston Hughes, Bessie Smith, Billie Holiday, Joe Louis, James Baldwin, Richard Wright, Ruby Dee, Lena Horne, and James Earl Jones.

The photographs Rudolph P. Byrd has selected for this volume come from the James Weldon Johnson Memorial Collection of Negro Arts and Letters, which Van Vechten established at Yale University. Byrd has arranged the images chronologically, according to the time at which each subject emerged as a vital presence in African American tradition.

Complementing the photographs are a substantial introduction by Byrd, biographical sketches of each subject, and poems by the noted writer Michael S. Harper. The result is a volume of beauty and power, a record of black excellence that will engage and inform new generations.

Johnson was also one of the black historical figures portrayed by African-American artist/illustrator Charles Alston.

Let us sing a song today for James Weldon Johnson, and the enduring harmonies of his hopes and dreams for justice.