American Untouchable

The actor who fought to integrate early TV.

BY EMILY NUSSBAUM

Racial diversity on television is in a state of rapid acceleration. In 2012, when “Scandal” débuted, starring Kerry Washington as a Capitol Hill fixer, it was the first network drama to feature a black female lead in thirty-eight years—a shameful milestone. The same fall, “The Mindy Project,” on Fox, made a brown girl the madcap heroine of a sitcom, not her best friend. Just three years later, “Scandal” faces off with “Empire”; “Black-ish” and “Fresh Off the Boat” have helped rebrand ABC as “the diversity network”; Aziz Ansari’s “Master of None” struts on Netflix; the Latina-centric “Jane the Virgin” lights up the CW; and Priyanka Chopra plays the lead on “Quantico.” There has been an especially remarkable migration of black actresses from movies to TV, among them Taraji P. Henson, Viola Davis, Angela Bassett, Gabourey Sidibe, Lorraine Toussaint, and Gabrielle Union. There is also a deluge of new talent on shows like Netflix’s “Orange Is the New Black,” one of several series that have opened the floodgates for performers who were long denied rich, complex central roles.

Hollywood, television included, is still run by white decision-makers, mostly men. The recent season of “Project Greenlight,” on HBO, made explicit how resistant to race talk Hollywood can be, a stifling culture of bros bonding with mirror versions of themselves. Behind-the-scenes numbers have barely shifted, particularly for directors. And yet TV is evolving rapidly. Much of this is due to a prominent new set of creative figures, among them Ansari and Kaling, Shonda Rhimes and Kenya Barris, Lee Daniels and Larry Wilmore, Nahnatchka Khan and John Ridley, Dee Rees and Mara Brock Akil, who don’t merely perform but run the show. Even newer is the increasing bluntness of many creators. When Viola Davis won an Emmy for Best Actress, for ABC’s “How to Get Away with Murder,” she gave a bold and unapologetic speech in which she quoted Harriet Tubman and declared, “The only thing that separates women of color from anyone else is opportunity. You can’t win an Emmy for roles that are simply not there.”

This is thrilling and long overdue. But it’s also a phenomenon that could easily recede, as it has many times before after periods of progress: in the early fifties, when television was brand-new; in the seventies, the era of “Roots” and Norman Lear; and again in the early nineties, post-Cosby, when black sitcoms thrived. One observer understood this ephemeral quality more than most: P. Jay Sidney, an African-American actor who built a four-decade career in television, all the while protesting network racism, in what Donald Bogle’s book “Primetime Blues” recounts as a “one-man crusade to get African-Americans fair representation in television programs and commercials.” Sidney is a footnote in history books, while other activists of his era are heroes. But he was there when the medium began, appearing on TV more than any other black dramatic actor of the time. Even as his résumé grew, Sidney picketed, he wrote letters, he advocated boycotts, he taped interactions with executives, lobbying tirelessly against TV’s de-facto segregation. In 1962, he testified before the House of Representatives. Nothing made much headway; he grew disgusted and disaffected. By the time Sidney died, in Brooklyn, in 1996, he had largely been forgotten, a proud loner who never got to see his vision become reality. “People today benefit from things that were sacrificed years ago,” his ex-wife Carol Foster Sidney, who is now eighty-seven, told me. “And they haven’t a clue.”

Sidney was born Sidney Parhm, Jr., in 1915 in Norfolk, Virginia, and grew up in poverty, in an era of public lynchings and Jim Crow. His mother died when he was a child; his father moved the family to New York, then died when his son was fifteen. According to a 1955 profile, titled “Get P. Jay Sidney for the Part,” he was a “difficult” child who landed in foster care but excelled academically—he graduated from high school at fifteen, then went to City College for two years, dropping out to enter the theatre. A lifelong autodidact, he is described by those who knew him as a guarded, sardonic figure, eternally testing those around him against an intellectual ideal. But even during the Depression he got jobs: he was in Lena Horne’s first stage play, in 1934; in the forties, he appeared in “Carmen Jones” and “Othello.” In a photograph taken at a campaign event for Franklin D. Roosevelt, Sidney is a dapper bohemian with a clipped beard. He also built a radio career, producing a series called “Experimental Theatre of the Air,” which, in a radical move, cast voices without regard to racial categories. Sidney collected his press clippings in a binder, which is saved at the New York Public Library’s Schomburg Center.

As the country came out of the Depression, and the civil-rights movement began, progress for black actors may have seemed possible. When television emerged, in the forties, it was a low-status but experimental medium, suggesting tantalizing opportunities for innovators. Yet a newspaper article from the mid-fifties, headlined “TV’S NEW POLICY FOR NEGROES,” depicts Sidney as the “single exception” to the exclusion of black dramatic actors. In TV’s infancy, the article laments, “The video floodgates were expected to be thrown open to experienced Negro actors. It never happened.”

“We took it for granted that we would be the last hired if hired at all and the first fired,” Ossie Davis recalled, in “The Box,” Jeff Kisseloff’s oral history of television. “And that we would wind up doing the same stereotypical crap that we did on Broadway.” “Amos and Andy” was typical fare. In the late fifties, Davis participated in a TV boycott in Harlem, in which black viewers turned off their sets one Saturday night. But it was Sidney’s rabble-rousing that had a direct influence on Davis’s career: “He used to walk around with a sign, accusing the broadcast industry of discriminating against black folks. As a response to P. Jay’s accusations, CBS didn’t give him a job, but they gave me one.”

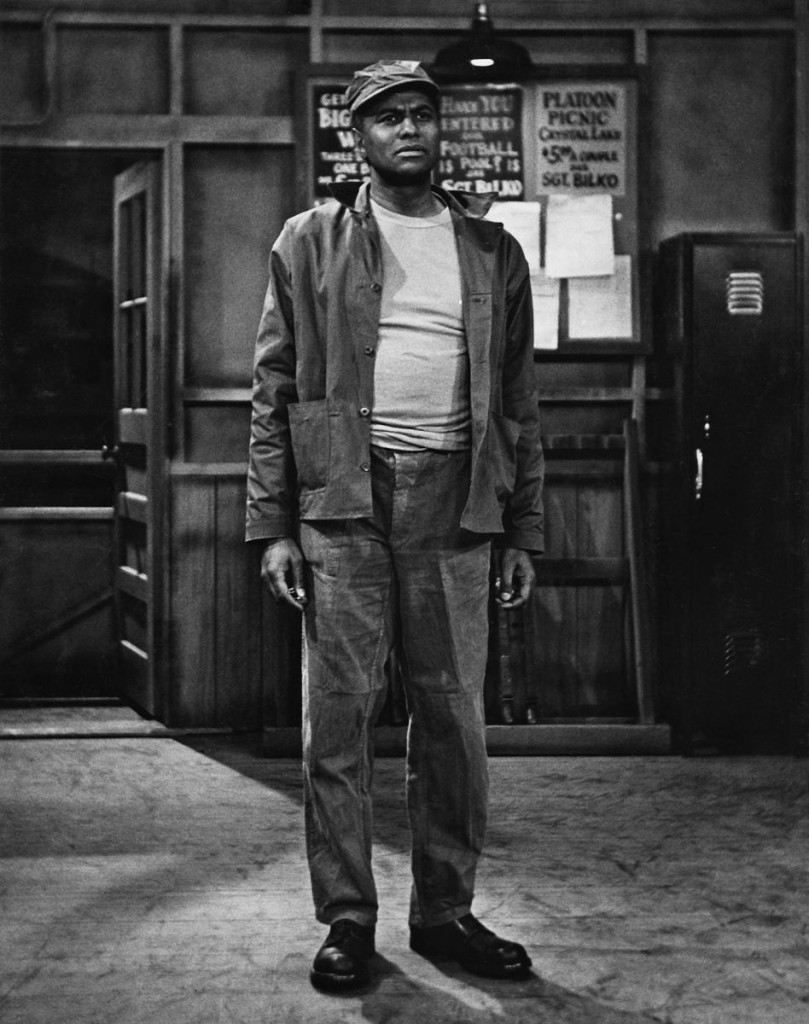

From 1951 on, Sidney made a living on TV, getting a few notable roles, including Cato, Hercules Mulligan’s slave and fellow-spy, in “The Plot to Kidnap General Washington,” in 1952. For two years, he appeared as one of two African-American soldiers on “The Phil Silvers Show”—a casting move protested by Southern stations. (The writers ignored them.) Over time, he amassed roles on more than a hundred and seventy shows, as well as a lucrative sideline in voice-over work and advertisements. (He played the onscreen role of Waxin Jackson for Ajax.) But the majority of his parts were walk-ons: doormen, porters, waiters. “I had a whole goddamned career of ‘Yassuh, can I git ya another drink, sir?,’ ” he told Kisseloff. “But I did what was available. I did not mix feelings with the fact that I needed money to live.”

With each setback, Sidney grew more frustrated, according to Foster Sidney, who married Sidney in 1954. Foster Sidney was the daughter of a dentist, educated at Howard University, a member of the Washington, D.C., African-American élite. She had persuaded her family to let her move to New York to be a French translator but dreamed of being an actress. Foster Sidney recalls, “He knew I had these aspirations, but he said, ‘One actor in the family.’ I, timid little thing, said, ‘Yes, dear.’ ” Their marriage was contentious, with Sidney resenting Foster Sidney’s “bourgeois” background; they separated, and had no children, but did not divorce until 1977. (In later years, Foster Sidney returned to acting, a period she calls “ten years in Heaven.”)

Nonetheless, Foster Sidney supported her husband’s activism, marching with him, as did a few other friends, including Sidney’s lawyer and close friend Bruce M. Wright—who later became a flamboyant activist judge, derided as Turn ’Em Loose Bruce for his opposition to racist bail policies. Even in freezing January, Sidney picketed CBS, the advertising agency BBDO, and other places, passing out flyers. He bought ads in the Times advocating a boycott against the sponsor Lever Brothers, which used black talent only in ads aimed at blacks. “It was his life,” Foster Sidney said. “There was nothing else he wanted.”

Sidney was particularly impatient with actors who hesitated to join his protests for fear of alienating their employers. “I didn’t give a shit about jobs for blacks,” he told Kisseloff. “I was concerned about the image of black people in television.” As early as 1954, he was writing to the Footlights and Sidelights column in the Amsterdam News, encouraging a write-in campaign, noting that “by not including Negroes in at least approximately the numbers and the roles in which they occur in American life, television and radio programs that purport to give a true picture of American life malign and misrepresent Negro citizens as a whole.”

In 1962, he testified before the House, arguing against “discrimination that is almost all-pervading, that is calculated and continuing.” He described two-faced producers, who used a nepotistic, friend-of-a-friend hiring approach, saying, “for most white people, Negroes are not actors, or doctors, or lawyers—not really—but are rather, all members of a secret lodge, domiciled in Harlem or some other Colored Town—all knowing each other and all experts on one another.” In 1967, Variety reported that Sidney had quit a job on “As the World Turns,” protesting the soap opera’s policy of not offering black actors contracts, as it did white actors. In 1968, he was quoted in the Times on whether the representation of black people in ads had improved. “It was like a man who’s been gravely ill with a temperature of 104 if it drops to 102 it’s better,” he said. “But, if the question is, ‘Has the progress been commensurate with the need?’ The answer is ‘No.’ ”

He also picketed David Susskind. A producer and talk-show host, Susskind was a famous liberal, but when he produced a show about American history that omitted blacks Sidney targeted his office. After Susskind died, Claude Lewis recounted Sidney’s confrontation with Susskind in the Philadelphia Inquirer. “You’re killing me,” Susskind said. “I mean to,” Sidney replied. “You talk that good stuff on TV, but you don’t practice what you preach. We’re here to say you’re a phony. If you really want to be the decent guy you pretend to be, you’ll offer opportunities to talented Negro performers, just as you do to whites.” When Susskind told Sidney that he would “earn an ulcer,” Sidney replied, “Mr. Susskind, I don’t get ulcers. I give ulcers. I’m on this line, not to win parts for me, but for others who deserve them.” A few years later, he appeared in a Susskind production, the gritty and iconoclastic social-justice procedural “East Side/West Side,” along with James Earl Jones and Cicely Tyson. The series was cancelled after one season.

Tom Scott, a younger actor and a model—he was one of the first African-Americans to be hired by Ford—picketed with Sidney. The two men talked nightly, strategizing; Scott was inspired by his friend’s savvy. When he couldn’t get press coverage, Scott recalls, Sidney had a female friend call the police and tell them, “There’s a nigger out there with a knife!” The cops showed up—and, with them, the media.

Yet, as the years passed, the door stayed locked. TV was still run by white people, emphasizing white stories. Sidney had bought a brick house in the Prospect Lefferts Gardens neighborhood of Brooklyn, where he retreated. In 1988, the Amsterdam News lamented the minuscule presence of black TV producers and writers, adding that Sidney’s activism had had as much effect as “ice cubes at the South Pole.” Sidney made one last significant TV appearance, in the TV movie “A Gathering of Old Men.” But in some ways little had changed: in his final movie, “A Kiss Before Dying,” in 1991, he played a bellman.

Foster Sidney lost touch with her ex-husband after their divorce; so did Scott and Lewis. But someone must have known him—the person who saved a document, labelled “ephemera,” that showed up at the Schomburg Center. On the envelope is scrawled “P. Jay Sidney memoir.” Inside is a fifteen-page handwritten account of Sidney’s life, on lined yellow paper, ending with a description of his death, from prostate cancer. It’s unclear who the author is, but the narrative is a raw and intimate confession, seemingly notes for a book. It’s possible that this is the project Sidney mentioned in a 1946 playbill, in a bio that describes him writing a book whose title is underlined at the top of these pages, “Memoirs of an American Untouchable.”

Written in the third person, the document swings wildly in tone; it’s laceratingly self-critical at some points, grandiose at others. It recounts Sidney’s father’s warnings: never to trust white people or women, never to be dependent. It ruminates on the cruel tumult of Sidney’s romantic life, but also on his longing, never-fulfilled, for an intellectual soul mate. He rails against institutions: the Catholic Church, Hollywood, even the civil-rights movement, which he felt made black people complacent. To the end, the document says, Sidney was rankled by a world that thought small. He had picketed for “black actors to be portrayed as respected people,” but an award he won honored only “his fighting to get black actors work on TV—just work, any old part. (This was not his aim at all! No one understood. He became very discouraged.)”

By all accounts, Sidney grew irascible with age: Lewis describes him as having become so sensitive that he saw slights everywhere. But there was a moment when Sidney believed that TV might someday reflect African-Americans in their full humanity. In a speech Sidney gave at a National Freedom Day dinner, in Philadelphia in 1968, he laid out this vision, with wit and elegance. The “bad image” of blackness, he said, was “like the air we breathe, and that makes it harder to recognize.” While African-Americans were accepted as “entertainers” for whites, only on dramatic shows might they be seen as “real people with real problems and real feelings.” White-centered programs “imply, insinuate, suggest—and I will use this word in the special way that possibly only Negroes will understand—they signify” that African-Americans were not truly citizens. Black audiences absorbed this message, too, learning to discount their own power—their economic leverage, especially. Sidney’s speech urged viewers to demand their place onscreen. Read today, it feels like a map to a world always just beyond the horizon. ♦