Malian photographer and “national treasure” Malick Sidibé passed away at 80 years old yesterday April 14 in Bamako. He is most notably known for is his black-and-white series taken in the 1960s in Bamako, documenting pop culture both outdoors and in his famed studio.

Malian photographer and “national treasure” Malick Sidibé passed away at 80 years old yesterday April 14 in Bamako. He is most notably known for is his black-and-white series taken in the 1960s in Bamako, documenting pop culture both outdoors and in his famed studio.

The 1960’s were a very rich era in Mali, as the country went from being a French colony to being independent. Many of Sidibé’s shots are considered legendary.

Revisit some of them below.

– L.

____________________

It’s hard to grasp the impact Malick Sidibé’s work has

had on our globalized visual culture. The legendary

Malian photographer passed away this week in Bamako

but his legacy is everywhere from the biggest fashion

publications and music videos to the hundreds, if not

thousands, of humble West African photo studios

working in the portrait style that he helped pioneer.

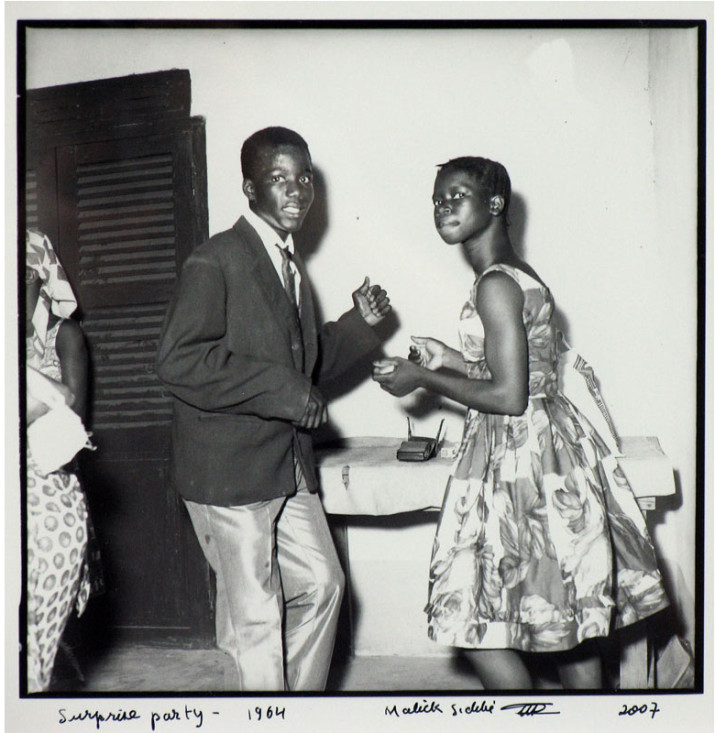

Beginning in the late 50s, shortly before Malian

independence, Sidibé took his camera to parties

capturing young Malians as they celebrated life. The

energy and beauty captured in these photos are as

striking today as when they were taken.

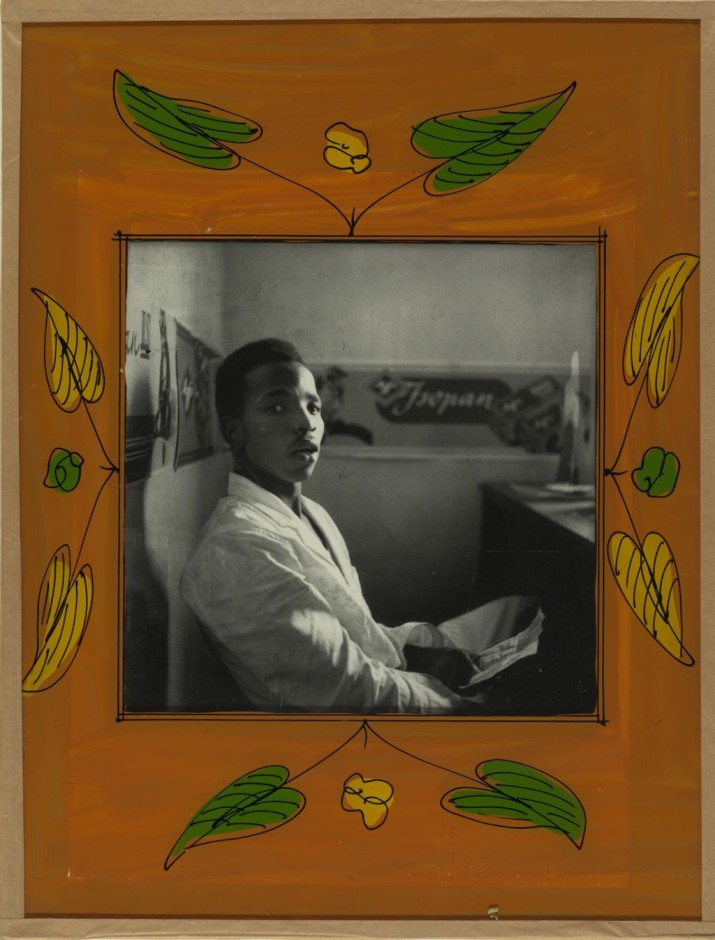

Sidibé later focused his energy on his photo studio

where he worked within the Malian studio

photography-style to create the now iconic

portraits that has made him internationally famous.

Later in life, this studio became a pilgrimage site

for photographers and photo-enthusiasts from

around the world. In 2010 he told The Guardian:

The studio was like no other. It was… relaxed. I did formal family shots, too, but often it was like a party. People would drop by, stay, eat. I slept in the developing room. They’d pose on their Vespas, show off their new hats and trousers and jewels and sunglasses. Looking beautiful was everything. Everyone had to have the latest Paris style. We had never really worn socks, and suddenly people were so proud of theirs, straight from Saint Germain des Près! It was, a fantastic period. Unique.

We will be posting memories of Sidibé all next week from artists and photographers who have been influenced by him and who knew him.

For now, I’ll leave you one of my own:

Long before I knew anything about the portrait style that Sidibé pioneered, I was a North American teen completely infatuated with Janet Jackson’s video for “Got ‘Til it’s Gone.” The video’s references to South Africa’s Drum Magazine alongside West African portraiture, and Sidibé’s work in particular, were arresting without any context at all and are just as impressive years later. It’s worth a watch.

More recently the French-Malian pop star star Inna Modja’s 2015 video for “Tombouctou” takes it one step further. This family friend of Sidibé shot her video in his studio in his visual style. It’s a stunning clip and a phenomenal song to boot.

Sidibé’s star is as strong today as it ever was. Earlier this week, Okayafrica contributor Tinashe TK reviewed the Sidibé show on now at the Jack Shainman Gallery in New York. He said about the work:

The strength of Sidibé’s images emanates not so much in the craftsmanship or technique he employs, but rather in the sincere directness with which the subjects meet the gaze of the camera. When you are looking at them looking back at you, it is almost as if they are daring you.

In a 2009 interview on the photo blog American Suburb X, Sidibe described what it was like during his early days.

In the 1960s, girls would sneak out of their houses to go dance. They would put something in their father’s glass of water so he would sleep and not notice when they left the house. Mothers were always the girls’ accomplices, and they were the ones who opened the door for them when they came home in the morning.

He also talked about his renown among Malians

Something curious and extraordinary is that now all of Mali knows my studio. Children, who normally call grown men tonton or “dad,” call me by my name, because names are the most important thing for artists. There are also women from the countryside who have named their own children Malick, and that fills me with pride.

We will be sharing more memories of the great photographer in the next few days. If you want to share your own memories please get in touch via submissions at okayafrica dot com.

>via: http://www.okayafrica.com/news/malick-sidibe-iconic-malian-photographer/

____________________

My interest in the politics and aesthetics of photography started from an unlikely source: Dambudzo Marechera, the enfant terrible of African literature. In his seminal text The House of Hunger, a coming of age novella set in the 60s and 70s, he writes about Solomon, a township photographer who could obliterate ‘the squalor of reality’ with his photographs. His customers, who have little hope of ever leaving the township can only realize their dreams of escape through the illusions he creates:

Photographs of Africans in European wigs… Africans who pierce the focusing lens with a gaze of paranoia. The background of each photo is the same: waves breaking upon a virgin beach and a lone eagle swiveling like glass fracturing light towards the potent spaces of the universe. A cruel yearning that can only be realized in crude photography.

The residents of Marechera’s house of hunger were growing up in the era of Malick Sidibé’s early photography. At the time, they were bombarded with images from colonial media institutions. These constructions of blackness were proverbial masks that, writes Laura Taitz in Emerging Perspectives on Dambudzo Marechera “served to hamper any attempt at self-definition or self-representation.” The masks embody the contradictions of colonized identities and the politics of representation, subjects Marechera obsessively grappled with in his subsequent works, Black Sunlight and The Black Insider.

Sidibé is the antithesis of Solomon. He set out to change the idea of black beauty and fashion through his street photography and studio portraits instead of imposing or maintaining the prevailing photographic models based on Western aesthetics.

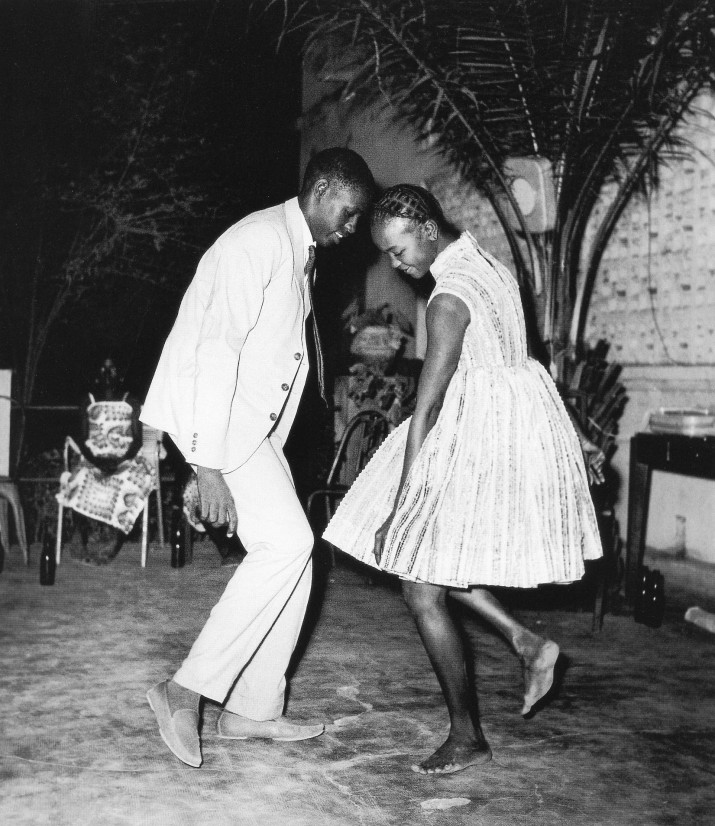

The first image of Malick Sidibé I encountered was the portrait of a young couple dancing at a Christmas party. It is one of the most iconic images from his oeuvre that spans a wide spectrum. The pose here is unrehearsed. It is graceful and dynamic and encapsulates the hallmark of Sidibé’s photography that captured the energy and hope of a generation of young black Africans living in a period of political and social transition.

His early photography affirms his participation in the decolonization of the 1960s, and in shaping the new look of young black and proud Africans who were consciously stylish and au courant. There is something rebellious and doggedly determined in their moves and gazes. By photographing them in the manner in which they wanted to be seen, Sidibé too was insisting on their right of being.

Looking at his photographs today, it is easy to see how productive they were in shaping the African worldview and creating a lexicon of black identity. Sidibé never stopped documenting youth culture and style in Mali. His photography journey began with youths dancing their way out of their colonial past into an era of freedom, expression and fashion.

The import of Sidibé’s contribution to the African sensibility and image is huge. His work is understated and yet sophisticated in its detail, especially the interaction of space, movement and subject. He was the first African and the first photographer to win the Golden Lion for Lifetime Achievement at the 2007 Venice Biennale that was themed, “Think with the Senses Feel with the Mind.” His place in the pantheon of photography greats is assured.

>via: http://www.okayafrica.com/news/malick-sidibes-photographs-danced/