MAY 5, 2015

SHE’S

BREEDING AGE:

DEHUMANIZING

PRICE FOR GETTING

PREGNANT

DURING SLAVERY

Most people know of slavery, but we don’t know about slavery. Specifically, we don’t know how dehumanizing it was to be a slave.

We might understand what it’s like to be denied freedom or dignity at an intellectual level. But for many of us, we don’t have a grasp on how horrible the institution was, in the day to day life of an enslaved person. Most of us don’t “get” what it was about inhuman bondage that made it so inhuman.

For example: what was it like to be slave mother?

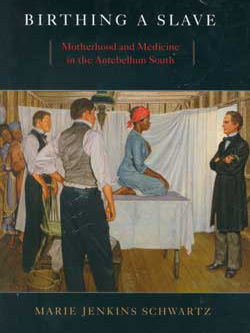

Some insights on this are given in the book Birthing a Slave: Motherhood and Medicine in the Antebellum South, by Marie Jenkins Schwartz. The book tells the history of a somewhat esoteric subject: the need of slaveholders, and the doctors they hired, to control and manage the bodies and reproductive lives of slave women.

But while the subject is esoteric, the details of how this played out in plantation life are chilling and disturbing.

The first chapter of the book, titled “Procreation,” has a gripping account of the stakes involved in the reproductive ability of slave women. I’ve provided some excerpts from that chapter below. Upon reading this, you will understand how lacking in humanity and dignity this peculiar institution was:

…an important aspect of slavery… has been all too often ignored: slaveholders expected to appropriate and exploit the reproductive lives of enslaved women. Control of one’s body was not a fundamental right of slaves. Emboldened by law and custom to do with human chattels as they wished, (slave) owners felt entitled to intervene in even the most intimate of matters. Women’s childbearing capacity became a commodity that could be traded on the open market.

During the antebellum era the expectation increased among members of the owning class that enslaved women would contribute to the economic success of the plantation not only through productive labor but also through procreation. The idea was at once both powerful and seductive and shaped the way women experienced enslavement, the way owners thought about the future of slavery, and the way doctors practiced medicine.

As of 1808, when Congress ended the nation’s participation in the international slave trade… the only practical way of increasing the number of slave laborers was through new births. If enslaved mothers did not bear sufficient numbers of children to take the place of aged and dying workers, the South could not continue as a slave society.

***

Women entering their childbearing years-especially those who had proven their fertility through the birth of a baby-sold easily and for a high price. Former slave Boston Blackwell, who witnessed the sale of two women in Memphis, Tennessee, reported that a girl of fifteen who had no children sold for $800, but a breeding woman sold for $1,500.

Human reproduction was so important to the continuation of slavery that members of the South’s ruling class willed their heirs the unborn children of slaves as well as living people. Anna Matilda King of Georgia assured her daughter that she would inherit not only the slave Christiann but also “her child and future children.” This wish to benefit future generations of slaveholding families pressed owners to look for ways of ensuring that enslaved mothers bore plenty of children. “If it was not for my children I would not care what became of the negroes,” Elizabeth Scott Neblett wrote her absent husband during the Civil War… Neblett maintained that she would gladly do without slaves to save the bother of managing them, but for her children’s sake she could not let them go.

***

Southern slaveholders’ perceived need for additional slaves did not play out solely as abstract political or economic rhetoric. It helped to justify the increased emphasis on the birth of children in the slave quarters. Every woman of appropriate age needed to bear children. Women who did not readily become mothers were subjected to scrutiny and possible action.

Purchases of slaves could be calculated to ensure that a planter had a sufficient number of women “of breeding age” and that each woman had a suitable sexual partner at hand. After purchasing Fanny from Virginia and Jim from Louisiana, Mississippi master Bill Gordon arranged for them to live together, which they did. Georgia slaveholder David Ferguson purchased Jacob Gilbert specifically as a husband for an enslaved woman.

Rewards for motherhood followed the birth of children. These included “extra clothing,” exemption from harsh treatment, even (rarely) freedom. Lula Cottonham Walker had to work hard as a slave in Alabama, according to her later testimony, but the mother of eight children was never beaten. If the master had a sow that gave birth to a litter of pigs each year, he would not take a stick and beat it. It was the same with slaves, she offered by way of explanation.

***

Barren women were a cause of concern.

Childless women could not expect any of the rewards or concessions available to mothers. Their work regimens were similar to those of men. Mary Buford did the same work as the men on her Arkansas plantation because, according to her niece, “she wasn’t no multiplying woman.” The disparity between men’s work and women’s work could be considerable. On the Bertrand estate in Jefferson County, Arkansas, the men were expected to pick 300 pounds of cotton, women 200. Childless women could be pressed to do as much as a man.

There were other repercussions for barrenness. Young women who had not demonstrated fertility faced the possibility of separation from family… If a married couple lived together for long without having a baby, North Carolina planter Joe Fevors Cutt would force both husband and wife to choose new partners. Former slave Henry Bobbitt maintained that many marriages did not last longer than five years because if no children were born within that period, husbands and wives were expected to find other spouses.

More commonly, childless women were sold. If a woman did not “breed,” in the parlance of the slaveholder, she was put on the market… “You better have them whitefolks some babies iffen you didn’t wanta be sold,” former Tennessee slave Alice Douglass recalled. Mary Grayson, enslaved in the Oklahoma territory, was sold twice for infertility.

The emotional pain of losing family members in this way is impossible for postslavery generations to fathom. Marriages were broken up, siblings split apart, older children separated from parents. Much of the selling occurred in states of the upper South, where there was a surplus of labor.

In the South, rhetoric surrounding barrenness took a peculiar turn. The focus was on enslaved women in general and on the reproductive history of specific women. The topic came up in everyday conversations related to the profitability of plantations, the management of labor, and the monetary worth of individual slaves.

>via: http://blackthen.com/pregnancy-during-slavery/