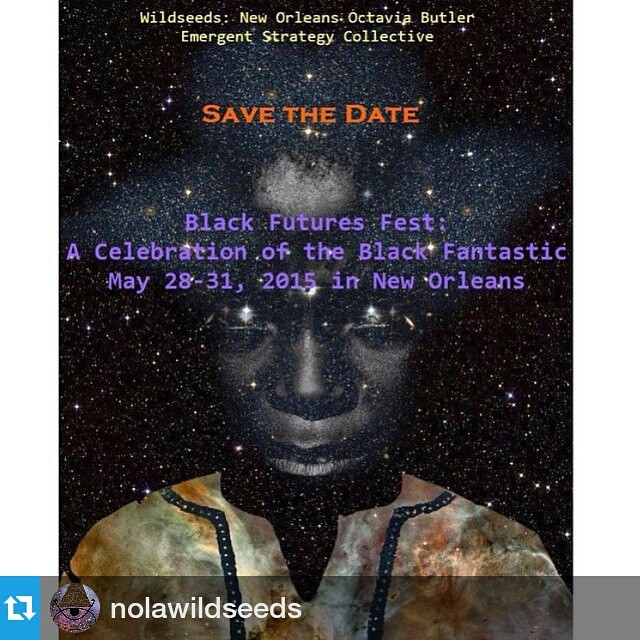

Front row: Octavia’s Brood co-editors Walidah Imarisha and Adrienne Maree Brown, with contributor Kalamu ya Salaam. Back row: New Orleans Wildseeds Collective, organizers of the Black Futures Fest.

MANHUNTERS EXCERPT

(Kalamu’s presentation, 31 May 2015 @ Black Futures Fest, book signing event for Octavia’s Brood. )

I was a child in detention. They say that it appeared I had cheated–my score was perfect and according to my social profile I was not supposed to be that smart. So they had jailed me until my appeal time. I stood in the middle of the cell, my arms folded. I said nothing to anyone.

When they called my name over the speaker and said that my mother had come to get me, I acted like I didn’t hear anything until two policeman came to get me. It costs more work points to stay in than to get out. School cheat bail was high but jail rent was higher. So I was doubly glad to go, but I never let on how relieved I was. I wanted to leave the holding room but I didn’t want to face my mother. My eyes were shut as I walked through the steel door, into the waiting area. My mother was there when I opened my eyes. Standing. Waiting. We walked out the station after I mumbled my way through the paperwork. I remember my mother signing for my release. Even now, I can clearly hear the scratch of the stylus on the computer screen where she signed. A hard tapping as she dotted an “i” and crossed two “t’s.” Poilette 437-70-8530.

“The name is not necessary. All we need is the number.” They said.

She signed her name anyway. I knew she would. When she finished she looked them in the eye. Two of the officers were like us.

“That’s all. You can go.”

My mother moved toward the door with long strides and waited for the trip switch to buzz. As the buzz sounded, she palmed the ID-plate. And we waited for the computer scan to ID check her palm impression. After a few seconds, a green exit light flashed on. The door slid back. We walked through.

All the way home in the tube we said nothing. Nothing. It was so hard. Nothing was so hard. Forty-eight minutes of nothing was hard. I kept fighting back tears. I pressed my forehead to the window. We were sitting close together. My mother and I. But we were not touching. All the way home. Nothing. She said nothing. She looked straight ahead. I said nothing, my face against the window. All the way home.

And then the long walk from the tube to our place. Just like I’m walking now. A long walk. Elder Imani says nothing. My mother said nothing. I say nothing.

I know I have done nothing wrong. Well not so much that I have done nothing wrong, because there is always something wrong, but at least, I am sure that I have meant to do nothing wrong. I have tried my best. Which, at moments like this, may or may not mean anything.

You try your best and no body speaks to you.

I had done so well on that test. I had everything right. And the teacher insisted that my getting everything right was wrong. But then if you didn’t get everything right on the test you didn’t have a chance to advance to city entrance level.

We had walked home in silence. When we got inside, my mother took off her stoic face. “Catherine, I can not keep you. You are no longer a child. I can not keep you.”

“Mama, my mama, my, mama, mama, mama. I. Mama. I know. I know. I know. Mama. I know.”

“Tomorrow, one of us must go to work.”

“I know, mama, mama. Mama. I know.”

“Next they will put you online.”

“I know.”

“If you run. They will get me.”

“I know.”

“If you go to work, it will kill you.”

“I know.”

“If I go to work…” her voice faltered. “I can not work.”

“I. Mama. I know.”

We were standing the whole time. Just like I am standing now, outside HQ. Waiting for a hearing. Waiting for a future I don’t control but which has so much control over me.

“Catherine,” is all she said. I heard each syllable softly explode into the silence. Cathhh. Haaaa. Rinnnnn.

“Mama. Mama. It is ok. It is ok. It. Is ok. OK? It really is. Ok.”

“Look.” She peals out of the plastic jump suit. “Look.” Her locator patch is red. “Look.” She points to the maroon glow beneath the skin on her left thigh. I look down and then look up her naked torso. She gave up wearing a bra long ago. She stopped wearing anything but a jumpsuit. My mama’s smell is so strong. We do not have enough points to visit the baths more than once a week. So we wait for rain. We stink. We stand it.

My mother reaches out to me and pulls me close to her. Her musky odor is so strong. I’m sure I smell too. But she folds me in a huge embrace. “Catherine. Remember I have a name.”

“Yes, mama.”

“Say my name.”

“Poilette. Poilette. Poilette.” We are standing and holding each other. I will always see that moment. The moment I realized that I was on my own. I had to run. My mama was sending me away. My mama was paying with her life for me to run.

At that moment I was frozen into a stiff column of flesh. And then she said, very, very softly, she said, almost so low I did not hear her, she said, I felt her breath against my ear stronger than I heard the sound of what she said, I could feel her lips move, her arms tighten around me when she said, “Go. Run.”

I stood there for several seconds trying to avoid the finality of what I had been told to do, trying to understand how was it possible to thank her for my life. With so little time left. Before I could say anything to her, she said a benediction into the hair on my head. “And may you find some god to shelter your soul.”

May I find some god.

Many years later I would have a name for this moment. The religious folk call it epiphany, the moment of realization. What I realized at that moment was not god but rather where god came from. God is one answer to our need to explain ourselves, to make sense of ourselves. But the moment you just accept yourself, then no explanation is needed and god is everything together and nothing in particular. But that was later, at that moment, my mother holding me and urging me to run–not telling me where to run–and knowing that she will die when she can not account for my absence. At that moment I had to believe in something, so I believed that god was life. The urge to live is god.

In some really deep way, her sacrifice was not a deathwish but a lifewish. My mother’s sacrifice was designed to pass life on.

We didn’t say anything else all night.

Left to right: Gahiji Akil Lumumba, Kalamu ya Salaam, Mwende Katwiwa. @octaviasbrood contributor Kalamu ya Salaam speaking in visionary panel about dreaming a #NewOrleans where Black lives matter to the larger society. #NOLAWildseeds #BlackFuturesFest