3/1/15

Through

Chuck Stewart’s

Lens,

a History of Jazz

There’s a well-worn bit of knowledge among musicians, when they talk about the virtues of practicing: Play until the instrument becomes an extension of yourself. That’s key for jazz and other improvisational musicians, where the aim is to close the gap between the ideas in their minds and the sounds of their instruments.

Chuck Stewart, a photographer whose visual legacy is intertwined with the history of jazz, subscribes to the same sort of philosophy. Fanatics who scrutinize the musicality of the form often extend that meticulous passion to the lives of its greatest stars: What was it like to perform with Miles Davis in one of his legendary ensembles? What was John Coltrane thinking as he listened to rehearsal takes from his album sessions?

Stewart was a witness to all of it, but he emphasizes the hard work that got him there over the marquee names of the subjects in his photographs. In fact, Stewart estimates that he’s provided the images for over 2,000 record covers, and boasts of having nearly a million images in his archive, shot over a 70-year career. But ask him about what it was like to photograph Duke Ellington, Count Basie and other towering figures of jazz, and you won’t immediately get the studio session stories.

“It was a job,” he responds on a lazy February morning in his New Jersey home. “I just wanted to take the best picture possible.”

Like asking a jazz musician where a particular improvised melody came from, asking Stewart how he’s been able to create the poignant moments that distinguish his photography is a fruitless exercise–in both cases, the artistry comes from the person behind the instrument reacting to his environment.

“It wasn’t about who they were, it was about how best they looked to me. And I wanted to take the best pictures possible of everybody I photographed,” Stewart says. “That’s why I don’t have a favorite picture.”

How Best They Looked To Me from Newsweek on Vimeo.

Stewart’s experience as a photographer began in 1940 on his 13th birthday, when his mother gave him a Box Brownie camera as a present. That same day Marian Anderson visited his school; he snapped photos of the popular singer and sold the prints he made at the drugstore for $2 apiece.

Attending college to study photography was an early example of Stewart’s professional good fortune; at the time he was applying, his girlfriend was working for politician Barry Goldwater, and given Stewart’s college-age draft eligibility, the future presidential candidate offered to help.

“He said, ‘If you can work it out to make sure that he gets into college, I can keep him there,’” Stewart remembers.

Only two schools then offered a photography major, Stewart said, and he settled on Ohio University, which, given the racial politics of 1945, was also one of the only institutions to admit black students. It was there that he formed a friendship with photographer Herman Leonard, who had returned to the university to finish his education after being drafted, and who later exposed Stewart to the idea of photographing musicians.

By the time Stewart graduated in 1949, Leonard had opened his own studio in New York, and was frequenting jazz clubs on 52nd Street and up in Harlem, photographing Dizzy Gillespie and Charlie Parker. As soon as Stewart finished his degree, Leonard hired him on as an assistant.

“When we went to clubs, it was the two of us; I had to carry the bags and that sort of thing,” Stewart says, noting that his early value was hanging lights and running extension cords for Leonard. “When Herman decided to take a picture, bang! I was ready.”

02_27_ChuckStewart_02Stewart’s 1964 portrait of musician Eric Dolphy holding a bass clarinet rests against a coffee table in his home in Teaneck, New Jersey on Jan. 31, 2015.

JARED T. MILLER FOR NEWSWEEK

His friendship with the photographer had another benefit: Leonard had been an apprentice of Yousuf Karsh, the legendary portraitist whose images of Winston Churchill, Ernest Hemingway and Salvador Dali have taken on an iconic status.

“I learned a lot from him and from Karsh, because when Karsh would come to New York he would take Herman and I as his third and fourth assistants,” Stewart said. “One of the first times he did that is when we went down to Princeton when he photographed Albert Einstein.”

Einstein would factor into another early experience years later; Stewart was eventually drafted but managed to find work as a military photographer, and in 1952 became the only African-American to shoot that year’s post-war atomic bomb tests.

In 1956 Marlon Brando hired his friend Leonard as a personal photographer for a trip to Asia, and Stewart took over the New York studio, inheriting contacts with record producers and musicians and building many more of his own.

From then on, he would roam recording studios and clubs to capture frames of jazz fixtures like Count Basie, Miles Davis and Frank Sinatra. Their expressions were often tense as they listen to the playback of a recording session, or when onstage, enraptured mid-song in a melody. Many photographs employ heavy use of black, framed in a way where some of the artists seem to be emerging only partially from the darkness of the stage. Along with creative framing, his photos often had shallower depth of field than was common in press photos of the time.

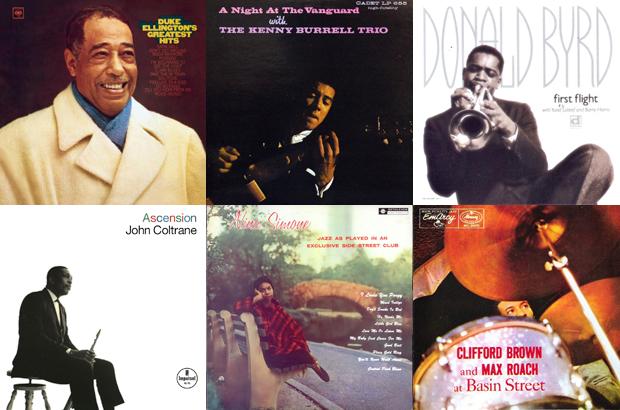

Clockwise from top left, albums for which Chuck Stewart has provided the cover photography: Duke Ellington’s Greatest Hits, A Night at The Vanguard with The Kenny Burrell Trio, Donald Byrd’s “First Flight,” Clifford Brown and Max Roach at Basin Street, Nina Simone’s “Jazz As Played In An Exclusive Side Street Club,” and John Coltrane’s “Ascension.” COLUMBIA RECORDS; CADET RECORDS; DELMARK RECORDS; MERCURY RECORDS; BETHLEHEM RECORDS; IMPULSE! RECORDS

He relied on his instincts and his personal impressions of artists in shooting their portraits, and he credits Duke Ellington with teaching him an early lesson about letting his own artistry enter his work. When the bandleader sat for a portrait early in Stewart’s career, the photographer quickly shot down the Duke’s campy mugging when he saw it through the frame of his 4×5 camera.

“He did everything I told him to,” Stewart says, “And when he left, I said to myself, ‘You mean to tell me that Duke Ellington did everything that I told him to do?’ That means that when people come to me, I’m in charge.”

Stewart was the only photographer present at the historic recording sessions for Coltrane’s A Love Supreme, but he doesn’t define his career by it–however frequently outside observers wish to do so. The refrain “it was a job” enters again; he was working for Impulse! Records when he photographed the saxophone legend and happened to be the only hired photographer. But as iconic as the album has become, Stewart’s photos weren’t even used for the cover; instead, producer Bob Thiele’s snapshot of Coltrane, which had been sitting on the edge of a desk when the musician eyed it, was approved.

“I called him and said, ‘What are you doing putting a picture like that on the cover?’ And he said, ‘Well, John liked it,’” Stewart says with a laugh.

Most of the record labels Stewart has photographed for have either merged or shuttered years ago. Stewart’s archive, composed in many cases without the knowledge that a moment might be historic or a figure might become famous, is now an asset. Stewart’s rolls and rolls of unused negatives–record companies needed only one frame for the cover–are now crucial records of entire eras of American music history. His life will be the subject of an upcoming documentary being produced this year, with interviews from Quincy Jones and key figures in Stewart’s career.

But it’s Stewart’s insistence on the basics–that he was a trained photographer before he was a jazz photographer; that he was just working a job rather than trying to guess who would be the next megastar; that he was just trying to translate the image he saw in his mind into the print he made in the darkroom–that defines him.

“I wanted it to be a picture that Chuck Stewart took of these people, as opposed to just another picture of this famous person,” Stewart says. “Like, for instance, Count Basie, there must be a million pictures of him. Why is mine distinctive? Well, I’d like to believe it’s distinctive because I took it.”