Contested Legacy

of Dr. Ben, a Father of

African Studies

Yosef Ben-Jochannan, 96, at the Bay Park Center for Nursing and Rehabilitation on Feb. 22. Credit Damon Winter/The New York Times

Africana studies professor Yosef Alfredo Antonio ben-Jochannan was born on December 31, 1918 in Ethiopia to a Puerto Rican woman, Julia Matta and an Ethiopian man, Kriston ben-Jochannan. Shortly after his birth, the family moved to St. Croix, part of the United States Virgin Islands, where he grew up as an only child. ben-Jochannan attended the Christian Stead School in St. Croix, Virgin Islands. After graduation from high school in 1936, ben-Jochannan attended the University of Puerto Rico where, in 1938, he received his B.S. degree in engineering. During that summer, ben-Jochannan’s father sent him to Ethiopia to study firsthand the ancient history of African people. He returned home and received his M.A. degree in anthropology from the University of Havana in 1939. ben-Jochannan holds Ph.D. degree in cultural anthropology from the University of Havana.

In 1940, ben-Jochannan immigrated to the United States and working as senior draftsman for architecture firm, Emery Roth & Sons, in New York City. Seven years later, he began leading tour groups to Egypt, Ethiopia, and Sudan. He led the groups twice a year for several decades. ben-Jochannan’s teaching career began in 1950 at Malcolm-King Harlem College and City College of New York in New York City. In 1976, he became an adjunct professor at Cornell University in Ithaca, New York. ben-Jochannan has worked closely with other notable Africana studies scholars including John Henrik Clarke, Edward Scobie, and Leonard Jeffries.

ben-Jochannan has written and published over forty-nine books and papers including, We the Black Jews, Black Man of the Nile and His Family, and Africa: Mother of Major Western Religions

The faded plaque to the right of the door said “Jochannan, Yosef B.,” but visitors to this nursing home on the northern edge of the Bronx knew the frail 96-year-old inside by another name: Dr. Ben.

As a sign of respect, many would also bend down on one knee.

The room was covered in mementos from a life spent between continents, weaving together the threads of the African diaspora: honors and awards, photos of Egyptian statues, kente cloth, a mug decorated with hieroglyphs and piles of letters from admirers and acolytes.

Yosef Alfredo Antonio Ben-Jochannan seemed unaware of the shrine that had accumulated around him. His eyes were barely open. He sat hunched in his wheelchair, dressed in baggy pants, a faded purple sweatshirt and a kufi.

One of his daughters held his hand; a granddaughter showed him photos of her own child on a cellphone.

Though he now had difficulty speaking, exhausted by even the smallest effort, Mr. Ben-Jochannan was once a powerful orator and a prolific author, one of the most vital and radical Afrocentric voices of his generation.

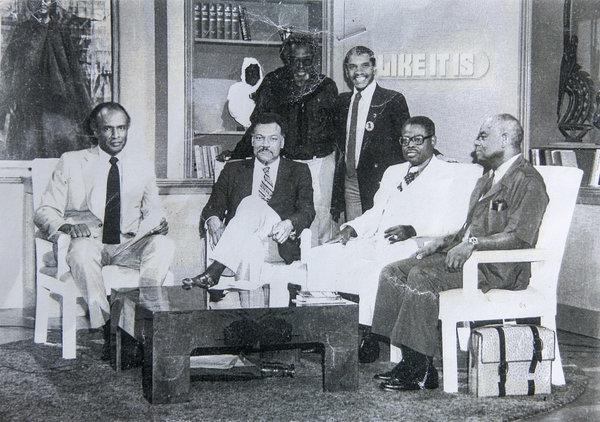

Seated, from left, Gil Noble, host of the public affairs television program, “Like It Is,” with Ivan van Sertima, Yosef Ben-Jochannan and John Henrik Clarke. Ralph Carter stands at right with an unidentified guest. Credit Damon Winter/The New York Times

And he may have been the last. On March 19, Mr. Ben-Jochannan died, leaving behind 13 children from three marriages and a generation of intellectuals and activists who looked to him for guidance.

His life spanned eras. When Mr. Ben-Jochannan was born, Africa was largely under colonial rule, the Voting Rights Act was a half-century away and the lynching of black Americans was at its peak.

To some, Mr. Ben-Jochannan was a sage, a self-taught scholar who dedicated his life to uncovering the suppressed history of a people, challenging narratives that had written Africa out of world history.

In the 1960s, Mr. Ben-Jochannan emerged as prominent figure in Harlem, pushing his anticolonial message to its limit, claiming that the very foundations of Western civilization, including Greek philosophy, Judaism and Christianity, were African in origin. He regularly lectured to crowded auditoriums; he was a disciple of Marcus Garvey and a confidant of Malcolm X, and he appeared on stages with Amiri Baraka, Al Sharpton, James Brown and Louis Farrakhan.

“He is a kind of godfather to all of us in African and Afro-American studies,” Cornel West, the author and activist, said. “I salute him. I was blessed to study at his feet.”

And yet to others Mr. Ben-Jochannan was an impostor and a historical revisionist. The Anti-Defamation League, troubled by books of his with titles like “We the Black Jews: Witness to the ‘White Jewish Race’ Myth,” stopped just short of calling him an anti-Semite.

His work, the group once wrote, was “blatantly inaccurate” and “unworthy of any educational institution.”

But Mr. Ben-Jochannan’s legacy is not confined to academic debate. As part of his enterprise, he took thousands of black Americans on tours of the Nile Valley, to visit the pyramids and temples of ancient Egypt, where he always took special care to point out the faces on statues and shapes of the figures in hieroglyphs.

Asked in the weeks before his death what drove him to make these repeated pilgrimages to Egypt, Mr. Ben-Jochannan cleared his throat and answered very slowly. “I wanted people to see their faces were the same,” he said.

Mr. Ben-Jochannan was born, he claimed, in Ethiopia, to an Ethiopian Jewish father and a Puerto Rican mother (herself from Yemeni Jewish stock). But there is little evidence for that other than his own word; some peers, and even a family member, have privately expressed doubts.

Most accounts agree that wherever he was born, Mr. Ben-Jochannan was raised in the Caribbean and moved to New York City around 1940.

Harlem at that time was swirling with various strains of black nationalism in the wake of Mr. Garvey’s pan-Africanist movement. This is where Mr. Ben-Jochannan found his voice, holding impromptu lectures in city squares and talks at community centers. He later began teaching at Harlem Prep, an experimental school that opened in 1967, and at Malcolm-King: Harlem College Extension, a two-year liberal arts school, in the 1970s and ’80s.

Mr. Ben-Jochannan’s self-published books — around 20 volumes in total, with titles like “Africa: Mother of Western Civilization” and “Black Man of the Nile and His Family” — were collaged with hieroglyphs and hand-drawn maps. Ignored by academia, they became staples in Afrocentric libraries.

“I consider Dr. Ben the greatest of the self-trained historians,” said Paul Coates, founder of Black Classics Press, who would later work as Mr. Ben-Jochannan’s publisher. “There’s still no one like him.”

Having already established a reputation among African-Americans, in 1973 Mr. Ben-Jochannan joined Cornell University’s Africana Studies and Research Center (at the time only four years old), in Ithaca, N.Y., as a visiting professor.

He was a distinguished figure at the Africana Center, eventually becoming an adjunct over his 15-year affiliation with Cornell. A painted portrait of Mr. Ben-Jochannan still hangs at the school.

During that period, Mr. Ben-Jochannan’s 15-day trips to Egypt, billed as “Dr. Ben’s Alkebu-Lan Educational Tours,” using what he said was an ancient name for Africa, were more popular than ever. They typically ran three times a summer, shuttling as many as 200 people to Africa per season. In 1987, one ticket, all expenses paid, was $1,545.

“I was always taught that the ancient Egyptians were Caucasian,” said Anthony T. Browder, who traveled with Mr. Ben-Jochannan in the 1980s. But in southern Egypt, Mr. Browder saw a statue of a pharaoh that left him speechless. “The face is African,” said Mr. Browder, who is the director of the IKG Cultural Resource Center, an organization devoted to the “rediscovery and application” of ancient African history. “It was mind-blowing, evidence of African greatness, thousands of years before our ancestors were enslaved.”

In accounts of his own life, some of Mr. Ben-Jochannan’s embellishments seemed to serve a larger purpose: gesturing to a distant past, establishing a grand narrative and creating a nearly mythic public persona. Others appear to be mere falsehoods or plain deceit.

Documents from Malcolm-King College and Cornell show Mr. Ben-Jochannan holding a doctorate from Cambridge University in England; catalogs from Malcolm-King College list him holding two master’s from Cambridge. According to Fred Lewsey, a communications officer at Cambridge, however, the school has no record of his ever attending, let alone earning any degree. Similarly, the University of Puerto Rico Mayagüez, where he also said he had studied, has no records of his enrollment.

It’s not clear whether employers had ever looked into Mr. Ben-Jochannan’s qualifications.

“People condemn me for not being an intellectual of the Ph.D. type,” Mr. Ben-Jochannan once said, reacting to questions later raised about his résumé. While he used the “white man’s credential” to go “certain places,” Mr. Ben-Jochannan said, he refused to “let the white man certify” his work.

Though beyond reproach to most acolytes, Mr. Ben-Jochannan was challenged publicly by classical scholars like Mary Lefkowitz, now a retired professor at Wellesley College. While Mr. Ben-Jochannan’s work was rooted in a desire to undo the damage done by colonial historians, Ms. Lefkowitz said, he was simply offering pseudohistory as an alternative.

“It’s a myth of conspiracy: ‘White people have taken away history and hidden the truth,’ ” Ms. Lefkowitz said. “But it’s all more complicated than that.”

Mr. Ben-Jochannan seemed unfazed by criticism.

“I don’t care whether white colleagues appreciate me as a historian or not,” he wrote once. “I’m writing for the African person all around the world.”

In the next decades, as most of his peers died, Mr. Ben-Jochannan emerged as the elder statesman of Afrocentrism. But like any vanguard, he may have been a victim of his own success, eclipsed by the younger intellectuals he influenced.

“That entire generation of self-trained historians really gave me my first sense of skepticism,” Ta-Nehisi Coates, an editor at The Atlantic, and the son of Paul Coates, Mr. Ben-Jochannan’s publisher, wrote in an email.

“What people like Dr. Ben were saying was, ‘History is not this objective thing that exists outside of politics,’ ” Mr. Coates wrote. “ ‘It exists well within politics, and part of its job has been to position black people in a place of use for white people.’ And that notion of skepticism goes with me in all of my work. It runs through everything I do.”