MARCH 10, 2015

From Jamaica

to Minnesota

to Myself

I knew I had to leave my home country

— whether in a coffin or on a plane.

I had just left my parents’ house in Portmore, a suburb outside Kingston, for my own apartment in the city: a one-bedroom studio, barely 600 square feet, with yellow shag carpeting, a tiny terrace enclosed in jail bars, a bedroom looking out on somebody else’s bedroom and a ceiling I could reach. I locked myself away from the neighbors with two deadbolts.

At 28 years old, seven years out of college, I was so convinced that my voice outed me as a fag that I had stopped speaking to people I didn’t know. The silence left a mark, threw my whole body into a slouch, with a concave chest, as if trying to absorb impact. I’d spent seven years in an all-boys school: 2,000 adolescents in the same khaki uniforms striking hunting poses, stalking lunchrooms, classrooms, changing rooms, looking for boys who didn’t fit in. I bought myself protection by cursing, locking my lisp behind gritted teeth, folding away my limp wrist and drawing 36-double-D girls for art class. I took a copy of Penthouse to school to score cool points, but the other boys called me “batty boy” anyway — every day, five days a week. To save my older, cooler brother, I pretended we weren’t related. At home, I lost myself in Dickens’s London, Huck Finn’s Mississippi River or Professor Xavier’s School for Gifted Youngsters. One day after school, instead of going home, I walked for miles, all the way down to Kingston Harbor. I stopped right at the edge of the dock, thinking next time I would just keep walking.

The University of the West Indies was a door: wide open. I found friends who seemed to have been waiting all summer for me to show up. I walked into the library with a back issue of Spin, and somebody asked if that was the one with Tom Waits. I’d known people who were geeky, sarcastic, well versed in the Smiths and “The Wrath of Khan,” but they had never been my friends before. Now I was dragged into word wars because one friend said “Time Bandits” was the greatest movie ever, when everybody knew it was “Life of Brian.” There were cheap liquor, potato chips, ironic quips, mix tapes. But when college ended, I returned home, got a job in advertising and shut myself down again. The people I had left behind were waiting for me when I got back.

The entrance to my cubicle was blocked by a boss with curious eyebrows who asked why all my magazines showed men on the covers, what GQ meant, where was Playboy? Every man in the office had a woman on the side, whether he was married or not, and even monogamous men were considered gay. Memories of childhood returned as nightmares: I was a kid again, frightened by school, praying to God every night, please let me wake up in another body. One that walked and talked right. That did not play house with a boy in the neighborhood that time when he was 8 and I was 9 and ruin him and myself.

One day I bought “Steppenwolf,” by Hermann Hesse, in a bookstore. Early in the book, an irrefutable argument for suicide jumped out and grabbed me by the neck: the scene in which the protagonist, having given himself his own expiration date, realizes that he can put up with anything, tolerate everything, suffer through all things because he knows when he’s going to check out. I hadn’t thought about killing myself since I was 16. But now there were nights when I woke up crying, or found myself out on the jail-terrace sunk so low into sadness that I had no memory of how I got there. I listened over and over again to lyrics from the song “I Found a Reason,” by the Velvet Underground: “I do believe/If you don’t like things you leave.” I cried for a sorrow that I did not know I had.

I was 28 years old, and I’d reached the end of myself. Electric words, “end of yourself” — I first heard them during a sermon in a Kingston church. The preacher was talking about when you reached the limits of your own wisdom and the only person left with any answers was God. A new friend in the office, who went to school in Canada and came in as my assistant, read my sarcasm as a defense tactic, though he didn’t know the reason, and said, “You should come to church this Sunday.” By then I was having panic attacks. I went to a doctor and asked, “Am I normal?” He said normal was a scale, with the left being normal and the right being abnormal, and I was somewhere on the left side of the middle. Then he gave me Xanax and asked if I wanted Prozac. Instead I got saved.

The church was called a clap-hands congregation, meaning charismatic, except it was full of upper-middle-class folk, and a cool pastor who drove a sports car. One Wednesday night, while Pastor was telling us that blessings were five miles upstream so we should, like Enoch, wait on the Lord, I started reading Salman Rushdie’s “Shame,” hiding it in the leather Bible case. I had never read anything like it. It was like a hand grenade inside a tulip. Its prose was so audacious, its reality so unhinged, that you didn’t see at first how pointedly political and just plain furious it was. It made me realize that the present was something I could write my way out of. And so I started writing for the first time since college, but kept it quiet because none of it was holy. I stayed in church for nearly nine years, telling a woman I tried to date that the real reason I had no interest in a relationship was Jesus. In 2005, when I was 34, I published my first novel, “John Crow’s Devil,” and wrote myself all the way to a book tour of the United States.

I stepped off the 6 train at Spring Street. Black combat boots busting a move. The phrase is nearly 20 years old, true, but I claimed it because I needed it, never more than right then. Levi’s Offender jeans sausaging my legs skinny; hip hug, butt squeeze, flaring below the knee and over my boots. Blue Stereolab T-shirt that stopped above the belt, Calvin Klein shades bought cheap at Century 21. Stepping out of the subway, emerging crotch first, posture moving from a slump like a question mark to a buffalo stance, an exclamation point. Walking to where Spring hits Broadway, the sexiest junction in all America, I’d heard. Where modeling agencies look down on modeling hopefuls strutting like peacocks.

Anonymity was a sea to dive into. Stonewall was a club to pass by — I was years away from having the guts to go in. Besides, I had no friends. In store windows, I saw a person who took me by surprise at first. The Strand Book Store, Tower Records, Other Music, Shakespeare & Co.; each was a step further away from the self I had left behind in another country.

It was getting dark, though summer stretches daylight, and I needed to be back in the Bronx. My younger half brother and his mother lived there, on a street of Jamaican immigrants. I walked to Barnes & Noble in Union Square, to the bathroom. I closed the door of the special-needs toilet, the same stall I used seven hours before, pulled my normal clothes out of the backpack and peeled New York off my skin. Back to loose T-shirt. Baggy jeans. Sneakers on my feet, boots in the bag. I took the 5 train home to the Bronx.

In creative writing, I teach that characters arise out of our need for them. By now, the person I created in New York was the only one I wanted to be. Over the next two years, I came and left often, pushing the limits of a student visa. I’d make friends but never get close enough to have them ask me anything too deep, playing at being aloof when I was really just shy, and I’d walk past gay bars, turn and walk past again, but never go in. Back home I fell back into church, knowing I didn’t belong there anymore. Once I forgot to code-switch in time and dashed to the bathroom in J.F.K., minutes before my flight to Kingston, to change out of my skinny jeans and hoop earrings. Eight years after reaching the end of myself, I was on borrowed time. Whether it was in a plane or a coffin, I knew I had to get out of Jamaica.

Then the college called. Macalester, in St. Paul, Minnesota. They liked my application letter, résumé and first novel and wanted to interview me. Minnesota, though. My entire knowledge of that state came from Prince’s movie “Purple Rain.” Everyone I asked said only: “It’s cold.” In January, I flew to the U.S. for an interview, then back to Jamaica, and waited, trying to feel nothing, just to keep from being disappointed. In March, Macalester sent an email. A one-year teaching job, full time. I packed up my entire life — my books — to ship to the States. It may have been only a one-year contract, but I was never going back. I felt no emotion. I didn’t see anything of Minnesota until the day I showed up for work.

I was shocked by my empty apartment, thinking “empty” meant a few chairs and a couch. I bought an air bed from Target. Seven days in, I put on jogging shoes and didn’t stop running until I saw something I liked, the downtown Minneapolis skyline. For a man always fearing what people thought, I was suspicious of “Minnesota nice,” everybody smiling and saying hello while they kept walking. But by the end of the first week, somebody I’d just met gave me a bicycle to get around; someone else bought me coffee mugs. Another professor, Casey, who moved here to teach as well, was into the band My Bloody Valentine and “Project Runway.” We became friends in 36 hours. In less than a year, I moved out of school housing to my first real apartment, and a young man who was my neighbor knocked on my door, asking, “Hey, you wanna smoke a bowl with us?” His name was Alex, and his friend across the landing was John-John. Two handsome straight boys who adopted me and became partners in finding me a life, mostly by getting me drunk at the Irish bar up the road.

I had never set foot in a gay bar without paranoia pushing me back out. During Gay Pride week, Alex and John-John dragged me to one called Camp, which was decorated with disco balls and drawings of octopus tentacles. Alex dressed as a cowboy, John-John as Travolta in “Saturday Night Fever,” both addressing themselves to people who hadn’t asked as my “bitches.” I was almost a cowboy, with a western shirt, vest and boot-cut jeans. I wasn’t quite sure what was supposed to happen, and neither were they, so we just drank.

Three years later, my best friend, Ingrid, visited from Jamaica. She looked at my walls, covered with photos and posters, books all the way to the ceiling, four shelves of vinyl, copies of GQ, Bookforum and Out magazines scattered everywhere, my “simile is like a metaphor” T-shirt, then at my face and said: “This is so you, dude. I’ve never seen you as you before.” I didn’t even realize when it happened, when I stopped playing roles. I wore my New York clothes to class, on the street, to clubs. Nobody cared that my jeans had a nine-inch rise. I no longer looked over my shoulder in the dark.

__________________________

OCT. 1, 2014

Once on This Island

Marlon James’s New Novel,

‘A Brief History of Seven Killings’

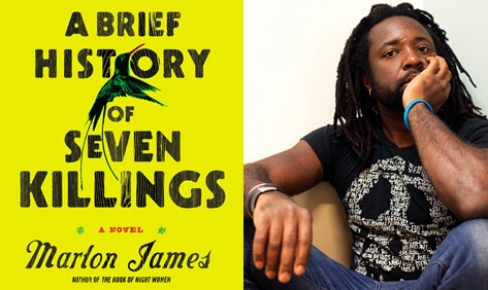

Marlon James on a visit to the Bronx, where “A Brief History of Seven Killings” concludes. / Credit Bryan Derballa for The New York Times

The novelist Marlon James grew up in Jamaica in the 1970s, which means he has a child’s memories of that politically turbulent and culturally fertile period. But as an adult, he keeps circling around that time and place in his mind, trying to make sense of what he could perceive only dimly then.

Out of that quest comes his third novel, “A Brief History of Seven Killings,” which begins as the optimistic glow of independence is giving way to the harsh realities of Cold War politics and the rise of gangs connected to the country’s two main political parties. From there, things get only worse: Crack cocaine appears and the gangs go international, setting up operations in Miami and New York.

“The idea for this book is the very first I had, even before the other two novels, because I always was interested in writing about the Jamaica I grew up in,” Mr. James said. “I thought it was going to be a short novel, that it was one person’s story. But I was wrong, because history is always shaping everything.”

Publishers Weekly declared that “no book this fall is more impressive than ‘A Brief History of Seven Killings,’ ” which comes out Thursday from Riverhead Books. In a review in The New York Times last week, Michiko Kakutani described Mr. James as a “prodigious talent” who has produced a novel that is “epic in every sense of that word: sweeping, mythic, over the top, colossal and dizzyingly complex.”

At 43, Mr. James is part of a new generation of Caribbean writers whose main cultural reference, aside from their home countries, is the United States rather than their former colonial power (in Jamaica’s case, Britain). These writers share some of the concerns of American peers like Junot Díaz and Edwidge Danticat and view the questions of identity and authenticity, which preoccupy older writers like George Lamming and the Nobel laureates Derek Walcott and V. S. Naipaul, as largely settled.

During a recent interview in the Bronx, where “Seven Killings” concludes, Mr. James called himself a “post-postcolonial writer” with a hybrid intellectual background. So while he read Shakespeare, Jane Austen and Henry Fielding in school, he noted, he also listened to Michael Jackson and Grandmaster Flash; a section of the new novel makes repeated references to Andy Gibb’s “Shadow Dancing.”

“Our sense of what it means to be a real Caribbean person is much more expansive, fluid and complicated” than that of earlier generations, said Nicholas Laughlin, a Trinidadian writer and critic who edits The Caribbean Review of Books, to which Mr. James has contributed. “Marlon is a writer who not only makes a mess of those boundaries and definitions, he totally obliterates them. That’s part of his power and appeal.”

“If you are going to read this as history, you’re bound to be disappointed and confounded.” MARLON JAMES / Credit Bryan Derballa for The New York Times

The plot of “Seven Killings” revolves around the assassination attempton Bob Marley a few days before he was to give a free concert in Kingston in December 1976, and required the novelist to dig deep into his creative toolbox. Marley, called simply the Singer in the novel, so dominated that period, Mr. James said, that his persona risked overwhelming the novel, which clocks in at just under 700 pages.

“I needed him more to hover over the book, as opposed to being in the middle of it,” he explained. He said he found a solution when he read Gay Talese’s Esquire magazine article “Frank Sinatra Has a Cold,”which focuses on the circle around that singer. Another help was Roberto Bolaño’s novel “The Savage Detectives,” which Mr. James described as “a very conscious template.”

Characters based on real-life people, including Cuban exiles and their C.I.A. handlers, play central roles in the novel. Jamaican politicians like the rival former prime ministers Michael Manley and Edward Seaga are very much present, too, along with leaders of the “garrisons,” the communities and criminal militias that their parties controlled.

Mr. James warns, though, that “if you are going to read this as history, you’re bound to be disappointed and confounded.” A lot of the novel, he said, is “just me being a trickster.”

But he does remember overhearing as a child some of the stories he incorporates into the novel. His mother was a police detective and his father a police officer who became a lawyer, “so the world of crime and politics and disturbances was always around,” he said, discussed in hushed and coded adult conversations.

A few years ago, Mr. James said, a European interviewer began a question to him with “as someone who escaped the ghetto….” He remembers objecting: “I grew up in the suburbs, like every other kid in every other part of the world. We had two cars, and we argued about things like ‘Is “T. J. Hooker” better than “Starsky & Hutch?” ’ ”

After studying at the University of the West Indies in Jamaica, Mr. James spent more than a decade in advertising as a copywriter, graphic designer and art director. His clients included the dancehall star Sean Paul, for whom he designed several CD covers, and The New York Times’s T Magazine. During much of that time, he said, “I made a big point of not writing seriously and even stopped reading for a while, too.”

But he was drawn back to literature by what he described as the “lack of a sense of possibility” he felt in Jamaica. Publishers and agents in New York showed no interest in a draft of what became “John Crow’s Devil,” his first novel. But when he took a chapter to a writing workshop in Kingston taught by a visiting American, Kaylie Jones, she was immediately taken by Mr. James’s writing and choice of subject.

“What leaped out at me right away was that he was a phenomenally visual writer with a lyrical, magical voice,” said Ms. Jones, who teaches writing at Wilkes University in Pennsylvania. “I was shocked that nobody had picked up this guy.”

A stint in the writing program at Wilkes enabled Mr. James to work on a second novel, “The Book of Night Women,” set on a sugar plantation in colonial times. He now teaches literature and creative writing at Macalester College in St. Paul.

Chunks of Mr. James’s novels, especially “Seven Killings,” are written in Jamaican patois. He describes himself as “bilingual,” fond of using dialect in speech and also to discuss serious questions of race, class and politics in the novel, but equally comfortable employing standard speech in interviews and the classroom, with an accent that is beginning to incorporate the flat tones of the American Midwest.

“When we are taking our business out in the public, that’s not how you are supposed to speak,” he said of patois. “It’s an embarrassment” to older and middle-class Jamaicans, he added, “especially if they hear I’m an English teacher. ‘Why are you speaking broken English?’ As if this is something that needs to be fixed.”