Medium

Everyone’s stories and ideas

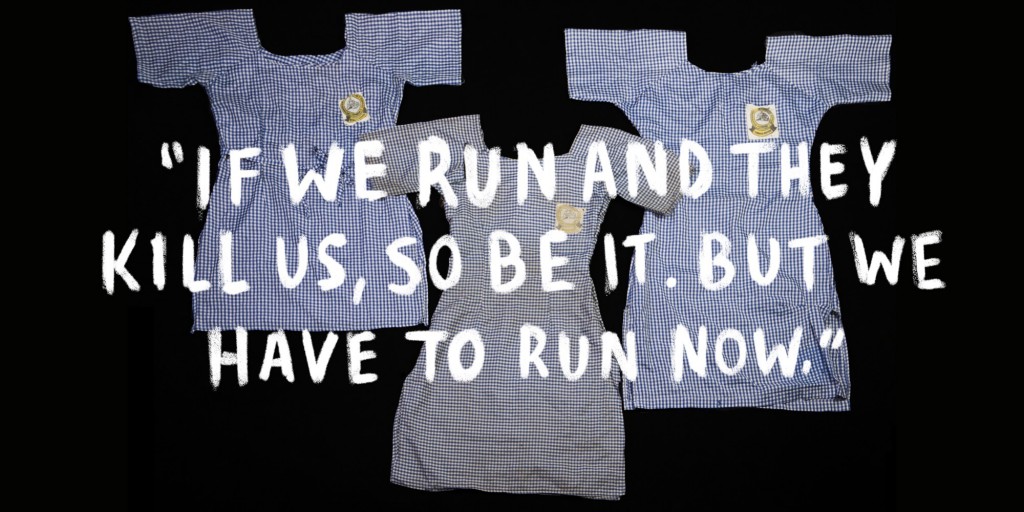

“IF THEY KILL US, SO BE IT.

BUT WE HAVE TO RUN NOW.”

Near the classrooms in the dusty schoolyard of the Chibok Government Secondary School, the Whuntaku girls hold court beneath the green lele mazza tree. There is no sign on the tree, no discernible markings; everyone just knows it’s their spot — where they gathered in the mornings, between classes, and after school to hang out, talk about boys, whatever.

A girl can’t just join the Whuntaku clique; she has to be from Whuntaku, a neighborhood in Chibok, a town in northeastern Nigeria that most people had never heard of before the “incident.” There’s an unspoken code among them: You could be friends with other girls, but you always watch out for your own. Earlier in the year, for example, a senior decided to haze a Whuntaku junior. She had told the junior to fetch her a bucket of water from the pumps outside, where the boarding school students collect water once a day for bathing. But when the Whuntaku girl said she was already on an errand for another senior and would have do it later, the senior yelled at the junior, said she was being “disrespectful.” She made her kneel on the floor of the bathroom for five minutes. The toilet that day was filthy; it’s where roughly one thousand girls in the school bathe, and no one had cleaned it. As the junior balanced her weight on her knees, she started to cry.

When the junior returned to the room the Whuntaku girls shared, the others told her to forget it. “Forgive,” they said. But the senior kept at it, always catching the junior on errands for other Whuntaku girls. She would make her kneel. The third time, the junior had just had an operation on her ribs. This is nonsense, the Whuntaku girls agreed. They stormed out of the dorm, found the senior, and, without discussion, started to beat her. They struck her with their hands, their legs. They chased her around the dorm: “We will kill you!” they said. They had no idea the senior had epilepsy, “second death” in the local tribal language. “She did like she died,” the girls later recalled. But when the shaking passed, they started again.

Chibok has a strict no-violence policy, and everyone knew suspensions were coming. That night, the Whuntaku girls ripped out a piece of notebook paper and passed it around, each one writing her name on a line. At the school assembly the next day, they simply handed the principal the paper, lined up in the order of their names, and then turned and walked out as they were called, heads held high:

Everyone at Chibok Secondary School got the message: When you touch the Whuntaku girls, you play with fire.

That mid-April Monday at the Chibok school was hot and languid, and by the afternoon the temperature crept up to 105 degrees — it was the hottest time of year, when the Saharan harmattan winds that crash through the arid countryside settle, but before the rainy season ruptures the heat.

The school, a few miles from Chibok proper, is a vast compound of freestanding buildings, classrooms, teachers’ quarters, and a dormitory, ringed by a low wall with a single gate. On one side, flat brushland stretches to the horizon; on the other, craggy mountains extend skyward. A few years ago, the all-girl school was integrated, and now a few hundred boys from town attended classes during the day, while girls from dozens of nearby villages boarded on the grounds. School had been cancelled for a month due to security threats from an extremist Islamic group called Boko Haram, whose nickname translates as “Western education is sinful.” That night, some 300 girls were on campus.

There wasn’t a girl at Chibok who hadn’t heard of Boko Haram, and none who didn’t fear them. The stories of what the group did circulated widely. They would kidnap girls and force them to marry, to cook and maintain their bases and safe houses. They would order them to kill prisoners they’d captured and brought back to camp and, if a girl refused, Boko Haram’s “real wives” would volunteer to slit the prisoner’s throat out of loyalty. If a captured girl had a child with Boko Haram — as all too often happened — they would force her to cook her own baby and then watch as the fighters devoured it.

The students of Chibok were terrified. False alarms were common. One night, a girl thought she spotted someone outside and led a screaming stampede toward the front gate — a pileup of sprained ankles and scrapes and bruises all because a girl had snuck out of the dorm to talk on her cell phone. After that, the principal told the students never, ever to run. The administration even called the town’s contingent of soldiers, who came to school and told the girls the same thing: If there was an attack — they should stay put. The army would protect them.

The summer before school started, Boko Haram had been pushed out of their stronghold in Maiduguri, Borno State’s capital, by a joint military and civilian operation. The group, which was started by students in the late 1990s arguing that only an Islamic state could fix Nigeria’s rampant corruption, initially got a foothold in the impoverished, Muslim north. But after a military crackdown they’d become radicalized and now they targeted politicians, traditional community leaders, and — increasingly — schools. At least fifty schools were burned over the past two years, and another 60 had been forced to close. In February, the group attacked a boy’s dormitory in neighboring Yobe state, locking the doors and setting the building on fire, burning 59 students alive. It got bad enough that in March the government closed all public secondary schools in Borno State—they admitted it couldn’t keep students safe. Chibok had only re-opened for seniors to complete their college-entrance exams. Everyone else stayed home.

When a student saw the vice principal pick up a piece of paper on the floor warning that Boko Haram was coming, the girls started gossiping. Would the principal cancel school? Postpone exams? The administration called the students together. It was a prank, they said — and it wasn’t funny. Boko Haram wasn’t coming, exams were. Everyone calm down and keep studying.

Endurance lay studying in her bunk in Moda House. She was a transfer student that year and had met Boko Haram before. The men had stormed her old school last year in the night, rounding up the female students. “What is the point of education?” they shouted. The girls were silent.

“Why are you being quiet? Don’t you know what to say?” the men demanded. “What’s the point of being here then?”

The fighters made the girls lie flat and press their faces down into the ground. Endurance didn’t notice how long she kept her eyes closed; she heard only their parting words: “We are going to leave you today, but if we come back and see another girl here, we’re going to kill her.”

After that, her parents enrolled her in Chibok — they thought it would be safer.

Endurance’s family lived in Askira-Ube, a town 15 miles from Chibok, where her father farms. Their house didn’t have electricity or a television — which made it hard for Endurance to study or learn English, the language of the college-entrance exams. Still, her parents had high aspirations for their daughter, the youngest of seven siblings and the first girl, they hoped, to finish school and go to college.

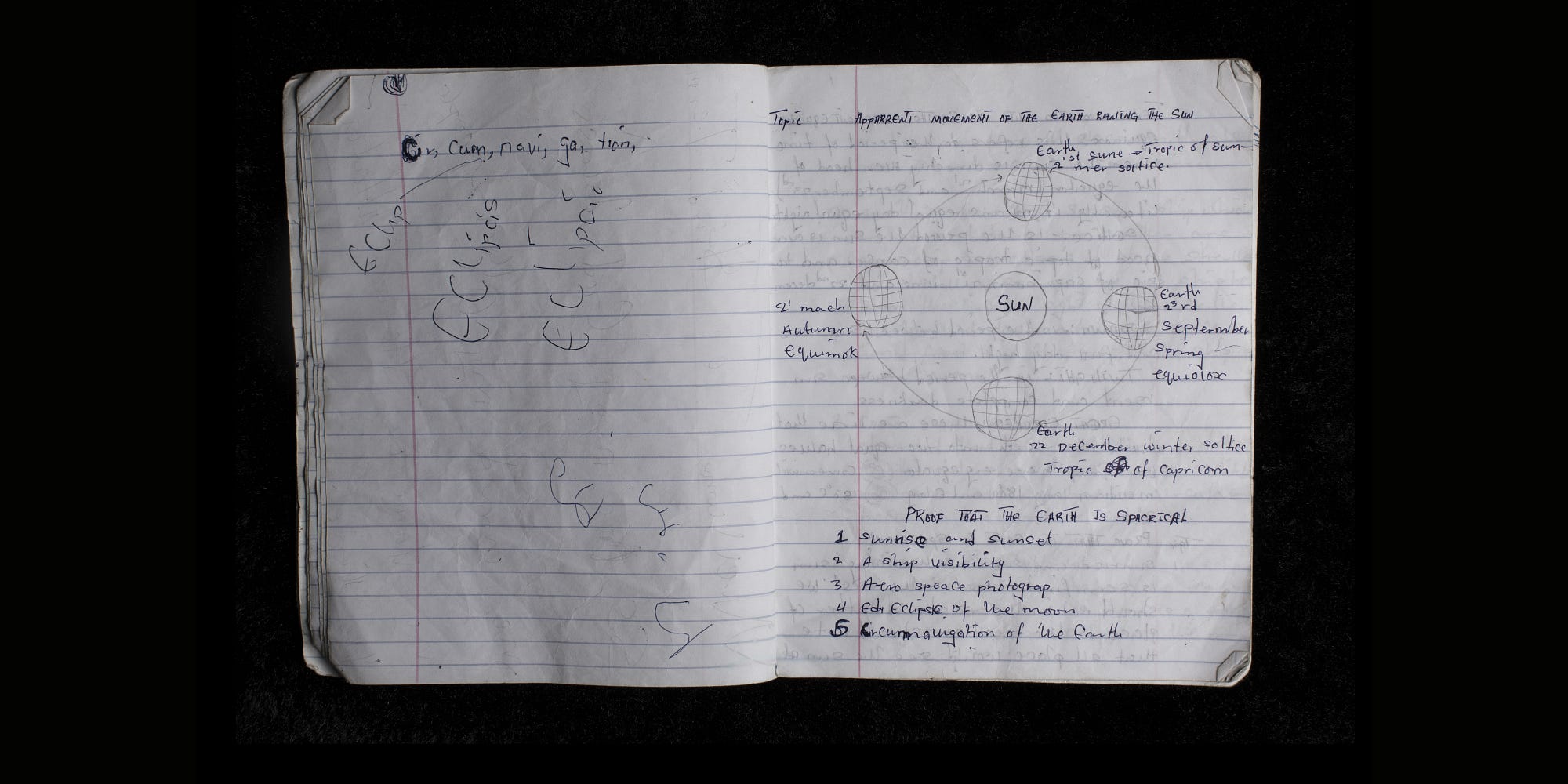

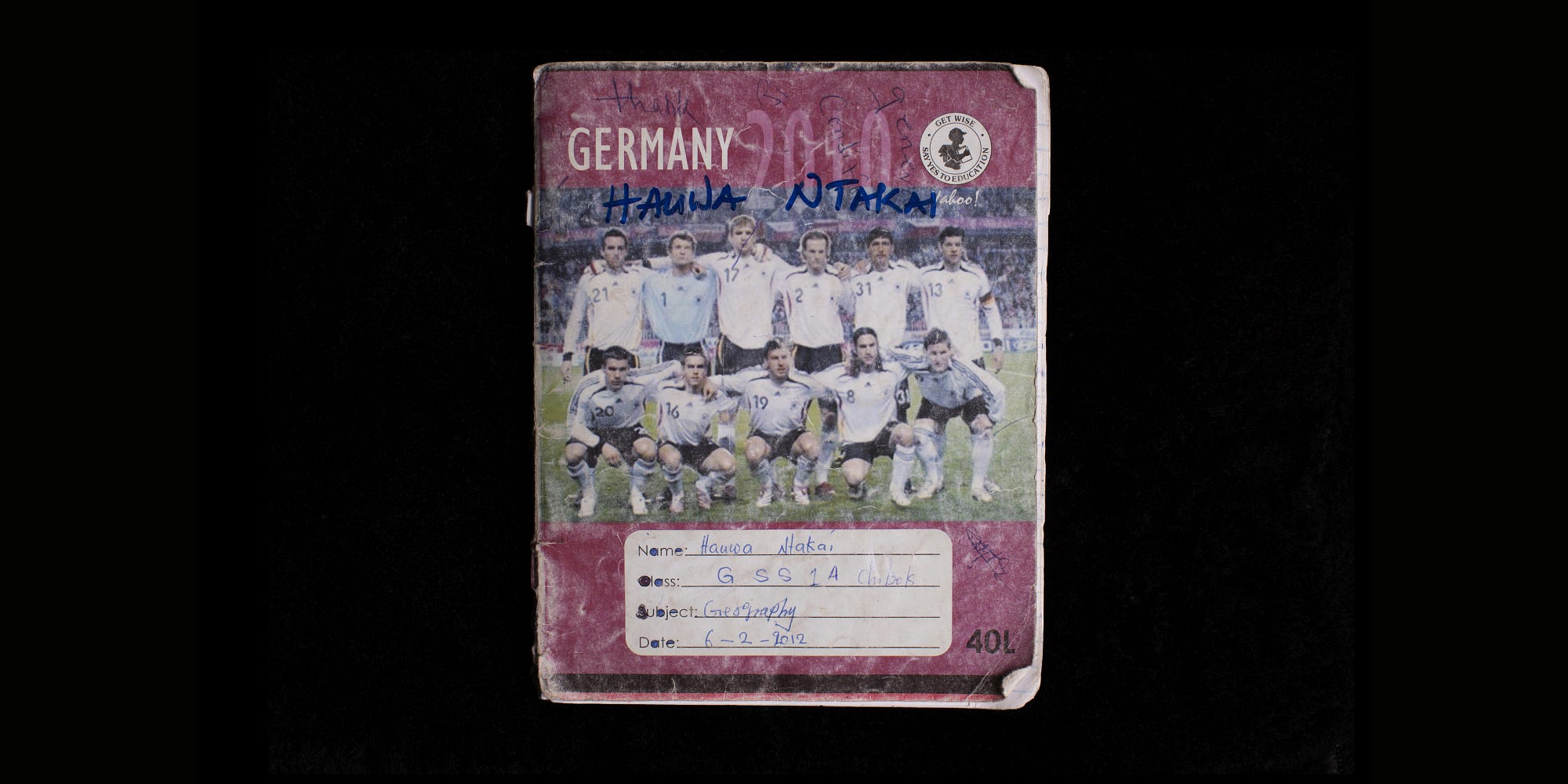

Endurance had come to Chibok early enough to claim the best bed in the dorm room—the one in the corner, with the biggest personal nook, where she arranged and rearranged her prized possession: biology books. Endurance hoped to become a microbiologist — a rare goal in Borno State, where most girls dream of family and only 28 percent of children are enrolled in school. Practicing Biology, Key Points in Biology, Modern Biology, Comprehensive Biology, and Intensive Biology. She kept them in her bed with her. At night, she liked to stack them under her head like a pillow.

The bed next to her belonged to her best friend, Mary. Endurance saw her on the first day, reading a book while everyone else was playing, foolishly. It turned out, Mary was third in the class. Her father was a pastor. Endurance was prim and wiry, with close-cropped hair — people joked that she dressed like a “preacher’s daughter.”

Together, they decided that this year was the most important of their lives. They weren’t like the popular girls at school, including the Whuntaku clan, who always seemed to be everywhere, walking around, heads high, talking to boys, laughing at inside jokes. They spent hours reading and talking about the Bible and how to live their lives in a good way. Endurance wasn’t sure how Mary knew all the good advice she gave — it was a gift God gave her.

“We should be careful with the life we live on earth. We should be careful because some people are going to come and say, ‘We are God.’ We have to love one another, because everyone is going to start hating and killing each other,” Mary told Endurance, and Endurance knew it was true.

The Whuntaku girls filed out of the Ghana room which they had christened “The Golden Room,” with a sign above the door. Evening prayer was the only time of day when Blessed and Hadiza were apart. As a Christian, Blessed stayed in the prayer area at the center of the hostel, while Hadiza, a petite girl with full lips and an intense stare, went to an empty classroom with the other Muslim girls. At the beginning of last year, when Hadiza had arrived at Chibok, there had been no beds in dorm room, so Blessed offered hers. From that moment on they shared everything—including a mattress.

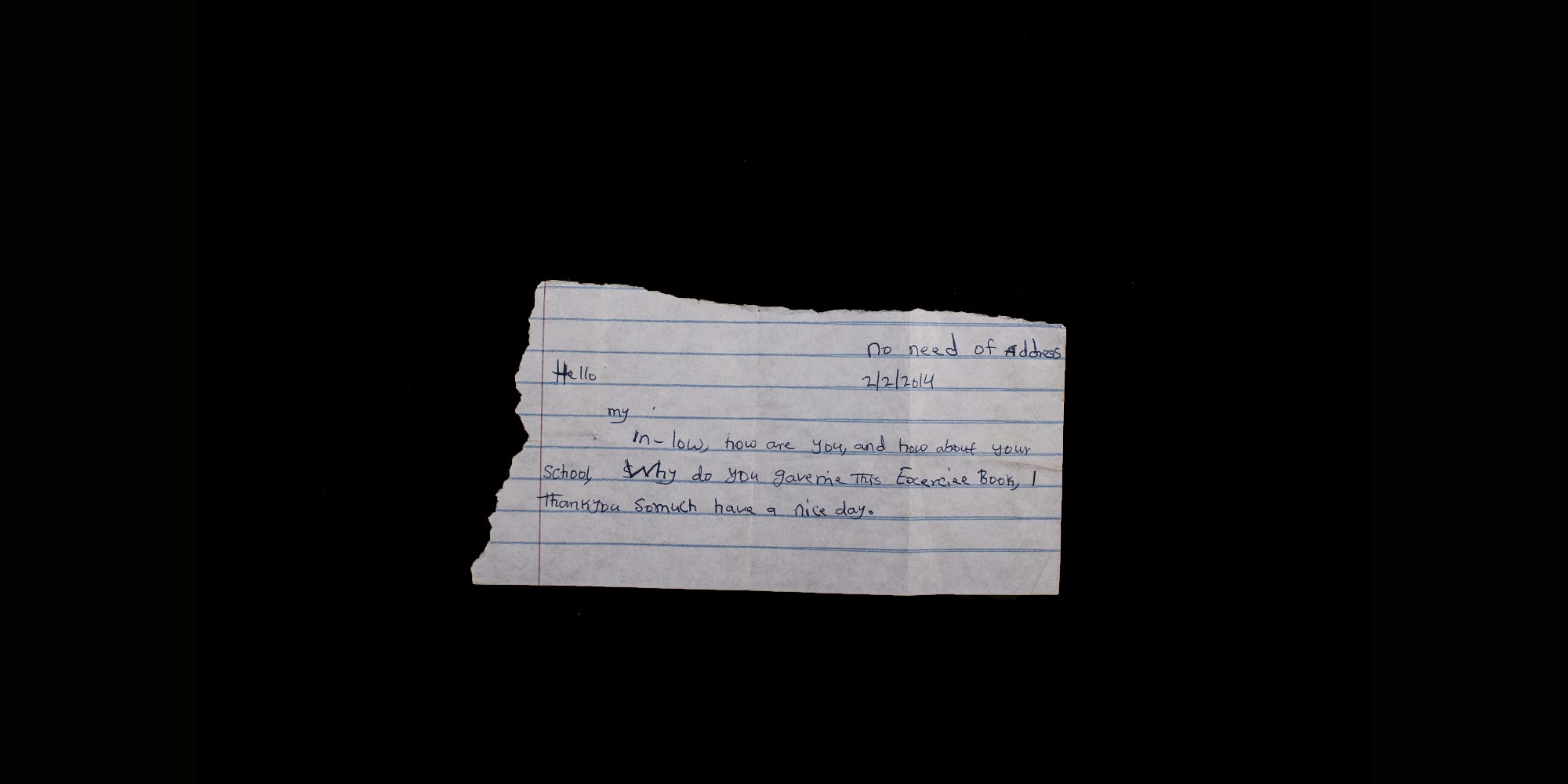

Blessed was the kind of girl other girls followed without really knowing why. Tall and confident with almond-shaped eyes, maybe her only social downfall was her choice in boys — specifically one called Cool Boy. It started when he passed her a note, saying he wanted to be her friend. Cool Boy was one of the most popular guys at school; she couldn’t help writing back “OK.” It took her longer for her to let him be her boyfriend. He gave her his phone number on a piece of paper, but she threw it away. Then one day she came to class and saw he had carved his phone number into her desk. “Now you can’t throw it away,” he proclaimed with a loafing grin. Blessed couldn’t help it: That was cool.

The problem was that Cool Boy was Muslim. “You’re just not supposed to be together,” said Salama, a Whuntaku girl and one of Blessed’s closest friends. Blessed knew Salama was probably right. Her parents, even if they agreed to the match, would never truly approve; Blessed would have to convert to Islam if they were to marry. She was the only girl in the family, and church is important in Chibok — a Christian outpost from the area’s missionary past. She thought her father, a police officer, would be crushed.

All of her friends, except Hadiza, were against it. Sometimes Blessed wondered if maybe Cool Boy hadn’t cast some kind of juju on her to make her forsake most of her friends in favor of him. If he had, it had definitely worked on her friendship with Salama, one of the most proper girls in the Whantaku circle, and that sucked.

Salama settled herself on the floor alongside Blessed in the front of the room and tried to concentrate on the prayer. It was quiet as the girls took turns. “May God keep Nigeria safe,” one girl began. “May the testing commission be kind to us and show us answers in advance,” another prayed. The girls were solemn. “As we sit and chill in the hostel and jest with our friends, and we say things about other people, may God forgive us,” someone else intoned. “May God keep us safe tonight,” another said.

The Golden Room was lit by torchlight. There was no electricity at Chibok, and after the sun set over the beige bush land the rooms grew dark and streaked with flashlight beams. Girls were draped across their beds, enjoying the slight drop in temperature, scattering their textbooks and notes.

Exam stress was like a blanket. Every sound was muffled. The room’s prefect, a Whuntaku girl, picked up a bucket. She started to drum. Salama, shy and pretty, always dressed immaculately, was sitting on her bed; she watched as Hadiza and another girl started dancing in the middle of the room. Blessed got up next to join them. Others rose, and suddenly the entire Golden Room was dancing — the girls twirling, slapping the balls of their feet, clapping, kicking their legs.

As the beat got faster, the girls moved faster. Salama could feel herself melting into the rhythm — all the stress of the exams, of school, of the future shed with each stomp. Blessed danced alongside her. Blessed was always so confident, so at ease in her own skin. Salama noticed that she was matching Blessed step for step. That made her proud.

The girls danced for hours — they didn’t remember ever having danced like this before. Exhausted and sweaty, Blessed and Hadiza pulled their mattress outside and fell asleep under the stars.

It started with a few pops in the distance that became a torrent. Endurance heard the noise from her bed and jerked up.

At Chibok there was one guard for the gate and one for the whole dorm. The dorm guard slept across from Endurance and Mary; they called him Kaka, the respectful way to address an elder male in Nigeria. Kaka was ancient — wrinkled and walked with a limp. It was impossible to know just how old he was. He rustled in bed. “I’m going out to look,” he told them, then shuffled away.

Outside, Hadiza was shaking Blessed awake and the two girls ran back into the Golden Room. Inside, there was only commotion and confusion.

Salama’s friend was shouting at her: “You idiot! Wake up! Can’t you hear what’s happening?”

Salama, still half-asleep, pulled on her blue-checkered uniform and ran to the Golden Room’s doorway. The sharp sounds of assault, like a thundering roar, were everywhere at once — she felt the earth shaking. Shadows of girls scrambled past and gathered in the darkness of the prayer area.

Endurance couldn’t wait for Kaka. Dressed in a T-shirt and wrapper skirt, she ran into the prayer room with Mary. They stood against the wall; Endurance took Mary’s hand and listened to the whispers. Mary’s breathing was heavy.

“Should we run?” the girls asked one another.

“We should not run. We should keep quiet. The principal said we should not go anywhere.”

“What is happening?” someone shouted.

“Is it them?” another asked. “Is it them?”

“Okay, everyone just sit down,” someone said. “Everybody just be quiet, maybe they will think there is no one in school!”

Kaka came back and found Endurance and Mary. “What are we going to do?” he asked. The girls looked up at him; there was little to be done. “We’ll just leave the rest for God,” Endurance said.

Kaka knew what Boko Haram did to men in situations like this — girls they might leave; men they kidnapped or killed. “They may have more mercy on you. They won’t have mercy on me. Let me go and hide,” he said and vanished into the shadows.

Endurance heard the sound of motorbikes. Two men in military uniforms walked into the dorm. “Don’t worry. Don’t run. We are with you,” one of them shouted. “Gather together! Gather in one place!”

In the prayer area, Blessed’s heart steadied. They were here to protect the school, just like the principal had promised.

The girls muffled their sobs and sat down.

In an instant, everything changed. More men charged into the hostel. “Allah Akbar!” the men shouted. “Allah Akbar!” The soldiers poured in, more and more of them, holding huge guns. It was dark and the girls couldn’t see them clearly, but the smell of sweat and adrenaline filled the hall. “Allah Akbar! Allah Akbar! Allah Akbar!”

After the last time, they had haunted Endurance. The dreams always started the same: white-clad angels singing beautifully, then her view shifted. Suddenly, there were dark shapes, people, monsters; she couldn’t make them out. They were screaming and shouting, and coming fast. She used to wake up before the monsters got too close. But now they were here.

“Everyone quiet!” one man yelled above the chaos, his face hidden by shadows. He must be the leader, Endurance thought. “Where are the boys and the men of the school?”

“They do day school,” someone answered.

The men weren’t there to intimidate. They wanted supplies. They wanted machinery — things that were impossible to get in the bush, where they made their home.

“Where is the machine for making bricks?”

“There’s no engine,” the girls whispered. “There’s no machine for making blocks.”

“You are lying! If you don’t tell us where it is — you know what we did to other towns, what you heard happened there will happen here.”

A group of men took two of the girls to lead them to the food stores. The other girls were commanded outside, past the lele mazza tree, and over to the gated entrance.

Endurance watched as the men divided themselves into three groups. One group guarded the girls; another loaded cars with sacks of rice, beans, pasta, and maize. The third started torching the buildings. It was all so practiced and efficient. Within minutes, the classrooms, the teachers’ quarters, and the storeroom were all bathed in orange flames.

Again the leader spoke up. “Go get your hijabs!” he shouted. A few of the girls riffled through book-bags for head scarves; others stood up, moving toward the hostel, which was so far untouched. Most of the girls remained seated.

“What about you Christians, don’t you have scarves?” the leader asked. “Are you all Christians?” The girls nodded.

“So does that mean we should just kill these — take them and burn them, too?” Endurance heard a man ask.

“No. Just mix them together,” the leader said. “Let’s go!”

Finally, the men set fire to the hostel: Everything the girls had known was now gone.

The leader wasn’t satisfied. “Where is the brick-making machine?” he shouted again. “I’m going to shoot this gun. If I shoot it four times, you are all going to die!”

The man shot. Once, twice, a third time.

A girl stood up: “It’s on the road!” she said. They dispatched her to show them. Salama felt her legs shaking.

Endurance started to pray, her eyes open as she sat in the dusty courtyard. She could feel Mary trembling next to her. She could hear screams and gunshots from the town, then a big explosion in the distance. Maybe one of the petrol drums in the market, she thought. The girls next to her were sobbing: “I’m the only child of my mom and I’m never going to see her again!”

A lone voice asked: “If I die, what am I going to tell God?”

Endurance’s left hand gripped her friend Christina’s, one of her other close friends from Moda House; her right hand held Mary’s. Christina held onto someone else, Mary did the same, and those girls held onto other girls, who held others. Endurance could feel their hearts beating as one.

The Holy Spirit told Endurance to pray. “If I have longer days on Earth, the Lord lead me out of this. If this is my last day on earth, let me see God,” she mouthed silently.

Christina’s body was still, taut like a spring; Mary was shaking. Endurance was calm. It will be like last time. They are going to tell us to go home now, she thought. Endurance willed herself to project calm on Mary, on all of them. She saw more men coming to the gate. “Get up!” they shouted, “Get up and follow this road!”

They are not going to let us go. Endurance stood up and said a prayer: “God give me direction of how to get back home. I am not scared.”

As the girls walked out of the gate, they were still linked. Endurance put one foot in front of the other, her eyes open, her mind clear. She focused on walking, one foot, then the other. They were careful to stay together in their web of hands — girls linked to girls linked to girls linked to God.

The main dirt road was wide, but hundreds of girls were walking together, placing one foot in front of the other as they had been ordered to. Endurance could see girls spilling over onto the side and into the bush. Boko Haram gunmen had them corralled like a frightened, stumbling herd.

Maybe 15 minutes went by; almost every girl in Endurance’s group was holding someone’s hand. “Why are you walking like that?” one gunman shouted at Endurance. She jumped. Everyone dropped hands. Endurance fumbled in the darkness. She found one hand near to her; it was Christina’s. Mary had disappeared, gone in the sea of girls and murmurs.

Endurance started planning. She whispered to Christina: “If we go where they are taking us, do you think we will be able to escape?”

“What do you think we should do?” Christina asked in Kibaku, the local Chibok tribal language; counting on the fact that Boko Haram — a group dominated by Fulani and Kanuri men from the northern part of the state — would not understand them.

“Well, even if we try to escape, and we get killed, at least our parents will be able to see our bodies,” Endurance told her. “That’s better than to go there and then have our lives spoiled.”

“How will we know when to run?” Christina asked her.

“The Lord will tell us the right time.”

By Endurance’s count, they had been walking about half an hour when Boko Haram shouted for them to sit down again. There was a big tree on the side of the road, and three trucks and a car parked beneath it. The fighters started re-packing food.

Blessed gripped Hadiza’s hand tightly. She watched as the men drove a lorry toward the group.

“Everyone who wants to live, get in the truck,” the leader shouted, “Everyone who wants to die, step over there!” He fired his gun in the air: pop, pop, pop.

Blessed pulled Hadiza’s hand, but Hadiza wouldn’t budge.

“Let’s go,” Blessed whispered.

“Do you want these people to kill you? Let’s enter!” She pulled her friend.

“I will not enter. Let them kill me here.”

There was a crush to move. Girls were pushing, jostling forward.

“Let’s enter!” Blessed pleaded. She could feel Hadiza’s resistance; her best friend’s hand was slipping away.

We are sleeping in one place, always. We are fetching water together; we are studying together; we are together, always. When we hear this thing, she’s the one who wake me up; she held my hand inside the hostel. Then, from the time that we came outside, we hold our hands together, and then we are moving. We are together, since the beginning our hands are together. Now, she left my hand.

Blessed was pushed to the front of the lorry. She sat down. The girls kept coming, crawling over each other to fit in the truck. A girl sat on Blessed’s leg, others gripped her shoulders. She was surrounded, suffocated by bodies.

The truck began to move. Inside the open-air container, it was quiet. The girls fell into each other, their bodies colliding and falling apart — their weight the only solid part of their existence. It was quiet, so quiet.

An hour passed — maybe more, maybe less — when Blessed heard Hadiza’s voice:

“Blessed! Come! Let’s jump down!”

“Hadiza, I am in the front! There are people on top of me! I don’t have a way to jump down.”

“Okay, Blessed. Please, if you have a place to stand up — stand up,” Blessed heard her best friend plead. “Please, let’s go!”

“Okay, Hadiza, I’m coming,” Blessed said. She tried to move, she pushed up, but she couldn’t. The girls had formed a cage of limbs.

“Hadiza! I can’t stand!” Blessed called. “Hadiza!”

“Okay, Blessed, until you return…”

After that, silence. When Blessed looked up, she saw only stars.

There were girls who jumped and girls who fell. Some grabbed tree branches that whipped across the open truck and swung out into the darkness. They leapt as if they knew what was coming, like synchronized swimmers vaulting calmly into a practiced routine they’d done countless times before. Endurance counted them go: One. Two. Three…

Salama saw them, too. They didn’t say goodbye — they just fell away, melting into the darkness. Salama struggled to move. She wanted to get to the edge and vanish as well. As she tried to stand, a girl pulled on her arm. “If you jump, I’ll report you to them,” she said. Salama stayed still.

From her spot in the truck, Endurance could see the next vehicle behind them in the convoy. It was a motorcycle; Endurance saw its lone beam, bouncing in the darkness. She measured the space between.

Endurance had promised Christina that God would let them know when it was time. Where was God now? The motorcycle beam got fainter. Was the truck was speeding up? Suddenly, Endurance realized she wasn’t holding anyone’s hand. Christina was gone — she had jumped.

Was this God’s sign? Endurance wasn’t thinking; she hunched down and sprung into the abyss.

The sun crept over the horizon, slowly rendering the dark shifting limbs into whole bodies and recognizable faces. But light did little to lessen the dull fear that had settled over the group. There was no expectation of the unknown, just blankness.

Blessed had watched the truck pass three villages. She had lost track of time when there came a clunking shudder — the truck had broken down. They were on a dirt road, with unfamiliar bushland in all directions, just flat and yellow, with a smattering of deep green Dogonyaro, acacia, and baobab trees. “Get down!” the men shouted, and everyone scrambled out. “Sit there!” they commanded, pointing to the sandy ground under a large tree. Now the girls got their first real look at their kidnappers.

They were more than a dozen men, wearing mismatching uniforms — police unit pants, military camouflage shirts — some with turbans covering their faces, others with nothing more than ordinary clothes and a gun. A few of them took out machetes and started cutting bramble and putting the thorny branches in a circle around the seated girls. It seemed like they had done this before.

The girls knew now that they were in a race against time. The longer Boko Haram held them, the harder it would be to return to their old lives. If anyone found out what had happened to them, they would be considered spoiled. There were stories about girls who returned home. Their families would try to hide the truth from their neighbors, from outsiders — No, this didn’t happen to us, they would say, our girls have been here all along. If found out, their daughters would never be able to marry. Their lives would be ruined forever.

“I want five girls, now,” said a man in a uniform. “Five girls, for cooking!” he demanded. Blessed watched as five girls stood up. She fidgeted on the ground. I need to find a way to run.

The men finished building the bramble barrier and went to fix the truck. The few that remained were stationed around the perimeter. They had left a small opening in the makeshift fence, a small corridor, patrolled by one man with a gun.

Blessed looked around and saw a few other Whuntaku girls sitting on the ground. She made up her mind, stood up, and walked to the corridor.

“Please, I want to ease myself,” she told the man in Hausa, the dominant language of northern Nigeria.

“Go back and sit down, you’re not going anywhere,” he said.

The man was young, tall, and fair-skinned; he had long hair.

“Please,” she said. “I need to ease myself.”

Blessed bent down and peed in the sand. She walked back and sat under the tree.

The men had gathered in a group by the truck. Blessed looked around; there were only a few men left watching the girls. She could hear faint crying.

“Give me your scarf?” she asked a girl sitting near her. It was a small, black-and-white checkered fabric, and she wrapped it around her tiny waist. Maybe they won’t recognize me, she thought. She stood up.

Her Whuntaku sister Salama was watching from the ground. What is Blessed doing? she thought. Salama was tired and hungry. She could hear nothing and everything. Then she heard only the voice of God: Stand up. Follow Blessed. Then, Satan: Sit down. Sit down. Wait.

The voices’ whirled around her head like a tornado: Follow Blessed; Sit down; Follow Blessed; Sit down. Salama wrenched herself up. She followed Blessed.

“Please, I need to ease myself,” Blessed asked the man again. Salama moved right behind her. Two more girls trailed after.

“Didn’t you just go?” he asked Blessed.

“No, that wasn’t me,” she replied. The girls stood silently by.

“Okay, come back immediately,” he said.

The girls didn’t speak. They walked out of the corridor and around the makeshift fence, past some bushes where they bent down.

“Okay, guys,” Blessed said, drawing them closer. “This is what’s going to happen now. We have to run. If we run and they kill us, so be it. But we have to run now.”

The girls nodded. Blessed peered out of the bush, the men had their backs to the girls; they seemed distracted by the food.

The girls ran without thinking. They ran without speaking. When they got tired, they rested briefly under the sparse trees, flattening themselves to the parched earth and making themselves very small. Then they ran some more. They thought they were deep in Boko Haram territory; militants could have been anywhere.

By the evening, Blessed and Salama and another girl (the fourth had run in a different direction from the broken down truck) took a break under a tree. They heard a cow mooing in the distance and saw a Fulani herdsman’s hut. The girls gathered. “These people are in the Boko Haram area. What if we go and they return us?” Salama asked. But Blessed was firm: They needed food.

When they entered the one-room straw hut, they found a couple there in the evening light. “Are you the girls Boko Haram kidnapped?” the Fulani man asked immediately.

“We heard you passing in the night. You’re safe here,” he told them. The girls weren’t sure they believed him, but they had no choice. The herdsman’s wife gave them new clothes, to disguise them, and plastic bags for their uniforms. They brought them water to bathe and fed them maize for dinner. That night, the girls cried and prayed and slept on the floor together.

The next day, the herdsman told them to follow the road and to ask people for directions home. In the afternoon, after walking all day, they rested beneath a tree. A man walked by. “You look really tired,” he said. “What’s wrong?”

“We are the girls who were kidnapped from Chibok,” they told him.

“Don’t say that!” he snapped, “Boko Haram comes to this village a lot.” He showed them the path they should take.

Later, a man on a motorcycle drove by and stopped. “What are you doing walking on the streets like this?” he asked.

“We want to go to Chibok,” they told him.

The man looked at their plastic bags. “What’s in there?” he asked.

“Are you the girls who were kidnapped from the Chibok School?”

“Okay, get on.” Less than an hour later, they were home.

Endurance couldn’t run. She had hurt her leg jumping off the truck, so she crawled. She saw the lone beam of the motorcycle headlight, but the machine didn’t see her. Christina found her in the darkness, but couldn’t lift her up. So Endurance pulled herself, with her arms, on her stomach, on her back, dragging herself through the brush. The ground was jagged and hard like stone, she could feel the rocks tearing at her clothes, at her skin. She thought she heard gunshots. Her elbow was bleeding.

A man with a bicycle, then a man on a motorbike, and finally a man with a car carried Endurance and Christina home. When Endurance got to the front door of her family’s small mud-brick house, near her father’s farmland, she saw her neighbors and her family gathered in the living room. Everyone was in tears, as if someone had died. When she saw her parents, she started crying, too. Her family told her how blessed she had been. “You should be serious, hold God closer to you, take care of yourself and live a good life,” one of her brothers said.

The next day, her brother Emmanuel took her to the market to buy new clothes and shoes — black, brown, and red . Everything she owned had been burned in the hostel, including her books. The family took her to the doctor to treat her legs. Endurance had never been to a doctor before. They had to make sure Boko Haram hadn’t done anything else to her. Afterward, she cut off all her hair. Just like that.

The dreams returned. But these dreams were different. There were no angels singing. She dreamed only of the girls. She dreamed about Boko Haram coming back and locking her into a room. Every blessed day, if she managed to sleep, she dreamed. Where is Mary now? Was it right to jump and leave her behind?

When Blessed arrived home, Hadiza came to her house right away. It was as if nothing had changed, they clung to each other and promised to do everything the way they always had. They would not go to the village market or get water without the other.

Blessed worried what Cool Boy would think. Was she ruined now? Would he still want her? Soon, he came, too. He greeted Blessed’s mother — she still didn’t know he was Muslim — and then found her. “I’m sorry this happened to you,” he told her. “I’m glad you are okay.” He told he loved her and promised to follow her anywhere.

When the girls’ parents got to the school the morning after the attack, they found nothing but the burnt shells of classrooms, matchstick dormitories full of metal bed frames and unanswered questions: Where had the teachers been during the attack? What happened to the security guards? How could a school be re-opened during an emergency closure without a security plan? Where are our daughters?

In Nigeria, questions like that hardly ever get answered. After waiting for the government to do something, a group of 100 fathers rode their motorbikes to the edge of Sambisa forest, the swampy national park where Boko Haram had supposedly set up their new headquarters in the countryside. They didn’t have guns, only machetes and knives. The nearby villagers told them to go back: “They have armored tanks; they have everything. They will destroy you,” the villagers said. The fathers relented.

It took president Goodluck Jonathan, who is running for reelection in 2015, three weeks to publicly acknowledge the kidnapping even happened — and when he finally did, he admitted that he didn’t know where the girls were. He then blamed the parents for not providing a list of names and promised to find them. His wife, Patience Jonathan, bemoaned the kidnapping, vowing to join the #BringBackOurGirls protests that had mushroomed across the country. Then she reversed course and declared the protests were merely an opposition-led plot to embarrass her husband in an election year. The first lady said the protesters were most likely Boko Haram members themselves.

That very day, the leader of Boko Haram, Abubukar Shekau, released a video saying he was going to sell the girls. A few weeks later, he sent out another that showed 136 girls sitting in hijabs reciting the Koran.

International media outlets picked up the story, and #BringBackOurGirls trended briefly. Michelle Obama posted a Twitter selfie holding up a sign in solidarity with the protest movement. Western governments promised to support a rescue operation. Then, just as quickly, the world turned away.

I meet the girls in a city in central Nigeria a little over two months after the incident. Blessed and Salama had been to the governor’s house in Maiduguri to help identify their friends in the latest video released by Shekau. Endurance had been to Abuja to talk to some foreigners about that night. She stayed in a hotel for the first time.

At first, the girls are all limbs and awkward giggles. They play on their phones and trade Christian and Hausa pop songs over Bluetooth. They’ve been told interviews like this are the only way to help the girls who are lost, but they’ve never told their story in detail. It’s impossible to know what parts of their tales are true, and what parts they’ve heard from others and repeated as absolute fact, the way only children can. There are moments where they get frustrated. No one has asked them about their lives before: How is this relevant to Boko Haram? How is this relevant to finding our friends?

How they managed to make it home and their friends didn’t is a question they don’t know how to answer. Sometimes they say it was God’s will. Other times, it’s something else. “The other girls were so scared, they did not have the courage,” Endurance tells me. “I have always had courage.”

This is undeniably true. The courage these girls showed in the face of men with guns is almost beyond comprehension. And yet the friends they describe, the ones still in the forest, are just as dynamic and headstrong as they are. In high school, friendships are blood bonds, so intense that the guilt of being free while their friends are in captivity is everpresent.

The timing of their abduction stays with me: They are 17, soon to be 18 — the years that mark the metamorphosis between girl and woman. It’s evident in the way they move their newly acquired figures, jutting out their hips when they pose for photographs, self-conscious and self-aware all at once. What had been their biggest year was now something else entirely. They didn’t know when they would retake their exams. They aren’t sure if this was just a thing that happened to them, or something that will define them forever.

At dusk after one of our interviews, Endurance and I are sitting in the den. The power has cut — outages are frequent across Nigeria— and the light is fading from the horizon. Endurance is showing me pictures on her phone: her friends, her house. She’s taken a photo of us together and photo-shopped a large pink heart around us as a frame. She smiles when she shows it to me. “Beautiful!” she exclaims.

Suddenly, she isn’t beaming anymore; she shifts her weight on the pleather couch.

“How do you think we can bring back the girls?” she asks, looking up from her phone. It’s as if she just remembered that they are gone.

“No,” Endurance decrees, shaking her head.

“There’s nothing stronger than prayer,” Salama lectures.

“I’m still praying, but… what kind of help do you think the government can do?”

“The government screwed them,” Salama snaps, her prim composure wavering. “What is the government doing?” She frowns.

“What do you think, Endurance?” I ask her. I watch her ponder silently. This is the girl who spent most of the time I was with her laughing and breaking out into tiny jigs. She thought seriously before answering my questions thoughtfully and at length. It’s the first time since our initial day together, when she broke down crying about Mary’s fate, that she looks small and fragile.

The international spotlight that had illuminated Chibok for a few weeks had faded, taking all those promises with it. Since the kidnapping, Boko Haram has only gotten stronger; they have taken over villages and towns, raised the black flag and declared their own caliphate. They have kidnapped more women. They have killed nearly three thousand people this year alone. The government has recently claimed a string of victories against the militants, and rumors of a possible prisoner exchange swirl, but negotiations have yet to yield results. Two hundred girls are still missing.

“Their lives have already been spoiled,” she tells me solemnly. “When they come back… Nothing, nothing can help them. They’ll never be the same.”

All of the girls’ names in this story have been changed. They chose their new names themselves.

This story was written by Sarah A. Topol. It was edited by Michael Benoist, fact-checked by Taylor Beck, and copy-edited by Lawrence Levi. Photographs by Glenna Gordon.