Thursday, November 7, 2013

Turbans, Voodoo, & Tignon Laws

in Louisiana

Posted by Barbara Wells Sarudy

During the 19th century, Marie Leveau (d. 1881), a devoted Catholic known as the Voodoo Queen, was generally a feared figure in New Orleans. Though apparently adept with Voodoo charms & potions of all kinds, Marie’s real power came from her extensive network of spies & informants. The New Orleans elite had the careless habit of detailing their most confidential affairs to their slaves & servants, who then often reported to Marie out of respect & fear. As a result, Marie appeared to have an almost amazing knowledge of the workings of political & social power in New Orleans, which she used to build her power as a voodoo priestess.

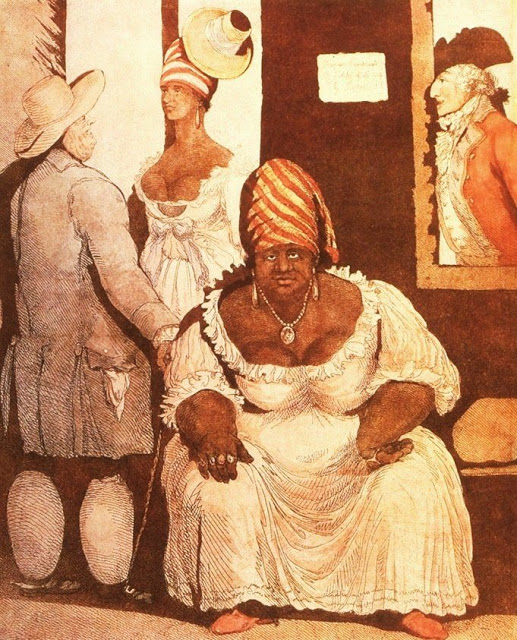

In the above portrait of Marie Laveaux of New Orleans, Marie was depicted wearing a tignon. A tignon is a series of headscarves or a large piece of material tied or wrapped around the head to form a kind of turban resembling a West African gélé.

A New Orleans journalist reported on a “voodoo rite” that he witnessed in 1828. “Some sixty people were assembled, each wearing a white bandana carefully knotted around the head…” At a given moment in the ceremony, one of the women “tore the white hand- kerchief from her forehead. This was a signal, for the whole assembly sprang forward and entered the dance”

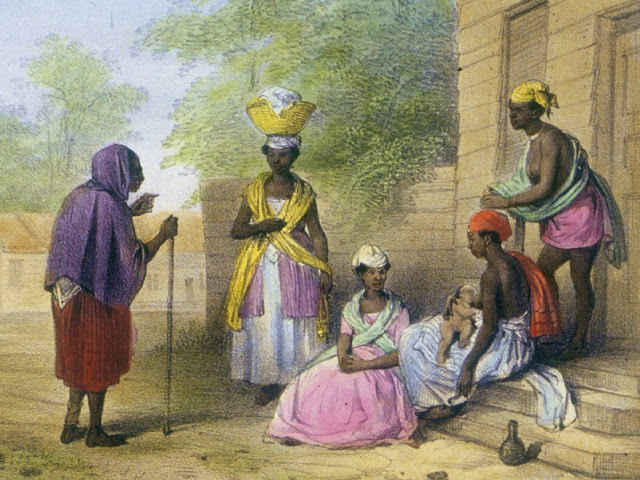

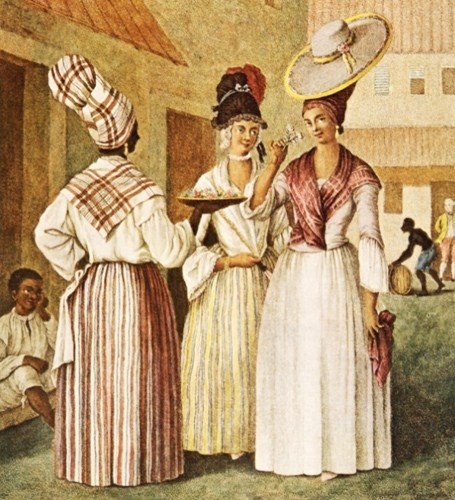

The tignon was the mandatory headwear for Creole women in Louisiana during the Spanish colonial period, and the style was adopted throughout the Caribbean island communities as well. This headdress was required by Louisiana laws in 1785. Called the tignon laws, they prescribed appropriate public dress for females of color in colonial society, where some women of color & some white women tried to outdo each other in beauty, dress, ostentation and manners.

In an effort to maintain class distinctions in his Spanish colony at the beginning of his term, Governor Esteban Rodriguez Miró (1785 – 1791) decreed that women of color, slave or free, should cover their heads with a knotted headdress and refrain from “excessive attention to dress.” In 1786, while Louisiana was a Spanish colony, the governor forbade: “females of color … to wear plumes or jewelry”; this law specifically required “their hair bound in a kerchief.” But the women, who were targets of this decree, were inventive & imaginative with years of practice. They decorated their mandated tignons, made of the finest textiles, with jewels, ribbons, & feathers to once again outshine their white counterparts.

Extramarital relationships between French & African settlers, occuring since slaves arrived in New Orleans about 1719, had evolved into an accepted social practice. The custom of freeing the children of such unions; the right of slaves to purchase their freedom; the policy of liberating enslaved workers for excellent service; and the arrival of free people of color from Haiti, Cuba & other Caribbean colonies led to the rise of a vocal free black population.

Through inheritance, military service, and a near monopoly of certain skilled trades, free blacks acquired wealth & social status. By the time Thomas Jefferson arranged for the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, New Orleans free blacks constituted nearly 20% of the city, while enslaved Africans comprised about 38% of the residents. Women of color, slave & free, continued to wear their bright tignons well into the 19th century, and they continued to attract the attention of men regardless of class or color.

Throughout the 19C, tignon was a local, New Orleans word for the headwrap, a variation on the French word, chignon which refers to a smooth knot or twist or arrangement of hair that is worn at the nape of the neck.

Elsewhere in America, headwraps were often referred to as kerchiefs by both African Americans & others.

The anonymous Mississippi planter who wrote “Management of Negroes Upon Southern Estates” (1851) noted: “I give to my negroes four full suits of clothes with two pairs of shoes, every year, & to my women and girls a calico dress and two handkerchiefs extra”

In 1863, E. Botume described the people who greeted her boat as it docked at Beaufort, SC, “Some of the women had…bits of sailcloth for head handkerchiefs”

Charlie Hudson, born in 1858, & enslaved in Georgia, remembered: “What yo’ wore on yo’ haid was a cap made out of scraps of cloth dey wove in de loom…”

Landscape architect Frederick Law Olmstead, a northerner who traveled in the South before the American Civil War, tells of yet another way in which blacks acquired headwraps: “(The negroes) also purchase clothing for themselves, and, I note especially, are well supplied with handkerchiefs, which the men frequently, and the women nearly always, wear on their heads”

A Savannah editor bemoaned the “extravagant” dress of city blacks. Wade says that the journalist, ” observing that a turban or handkerchief for the head was good enough for peasants,…noted that ‘with our city colored population the old fashioned turban seems fast disappearing’ ” (Savannah Republican 6 June 1849)

Louis Hughes, born 1843, enslaved in Mississippi and Virginia, noted: “The cotton clothes worn by both men and women (house servants), and the turbans of the latter, were snowy white” After the family moved to the city, Hughes recalled, “Each of the women servants wore a new gay colored turban, which was tied differently from that of the ordinary servant, in some fancy knot”

In the Slave Narratives, Ebenezer Brown, enslaved in Mississippi, said: “(My mammy) wrap her hair, and tie it up in a cloth. My mammy cud tote a bucket of water on her head and never spill a drop. I seed her bring that milk in great big buckets from de pen on her head an’ never lose one drop.”

John Dixon Long, a white observer, remarked on a prayer-meeting held by enslaved people in Maryland in 1857. “At a given signal…the women will tighten their turbans, and the company will then form a circle around the singer…”

Louis Hughes, born 1832, enslaved in Mississippi and Virginia, remembered “once when Boss went to Memphis and brought back a bolt of gingham for turbans for the female slaves…red & yellow check…to be worn on Sundays”

In 1863, Fanny Kemble’s description of the slaves on her husband’s Georgia plantation included: “head handkerchiefs, that put one’s very eyes out from a mile off…”

__________________________

7 March 2013

Tignon of Colonial Louisiana

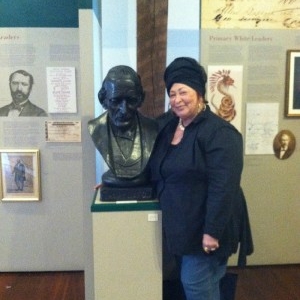

Photo Credit: Jeila Martin Kershaw, photographer. “Barbara Trevigne Wearing Tignon.” Photograph. New Orleans: April 2013.

When Governor Esteban Miro introduced his Edict of Good Government in 1786, he meant to insult the women of color in New Orleans, but instead they turned it on his head and ignited a fashion craze that was sported by white and black women alike.

Introduction

Throughout history, dress has served a purpose. Dress can protect you from the elements, display your status in a hierarchical society, inform others of where you are from, or simply just affirm that you are fashionable. Hairstyle, as a subgroup of dress, proves no different. Men and women have always changed the style of their hair according to the changing of time and hairstyle remains a topic on the constant loop of what is in fashion and what is not. It is no wonder, then, that the women of colonial Louisiana took the same pride in changing their look with elaborate hairstyles and head coverings as women do today, although women today use different methods. The common hairstyle in colonial Louisiana employed a head covering, known to modern readers as a tignon. While we refer to these coverings as tignons, this word was not common among those who used tignons according to Barbara Trevigne. [1] Today the tignon is most associated with African American women due to the alleged “tignon law” set in motion by a governor during the Spanish possession of New Orleans, but this association cannot be attached only to African Americans as many free white and creole women also sported the tignon. Through the examination of portraits of colonial Louisiana, women’s armoire inventories, tignon “laws,” and the history and evolution of these head coverings, the tignon becomes a statement for white and black women alike and fails to serve its initial purpose of degrading some while lifting others.

History

Head coverings and hair ornaments have been an integral part of women’s fashion since the ancient Egyptians, whose ornate head pieces and crowns can be seen in any Egyptian artifact, and continue to be popular today in many forms. According to Barbara Trevigne, women, both black and white, in New Orleans have been wearing hair ornaments since the origins of the colony and some of the earliest hair decorations found in inventories are the traditional tortoise shell combs and lace mantillas of Andalucia, Spain. [2]Traditional French ornamentation included more complicated styles originating with the ever-changing hair of women like Marie Antoinette and finally diluting down to the feathers and jewels found in New Orleans. If women chose to wear their hair in a high style, as was common, it was custom to accompany that style with an appropriate covering, which is where styles like the mantilla and tignon come into play. [3] The mantilla and lace head coverings are typically seen in Spain, and can be seen there today when women wear traditional Spanish dress.

Fabric

The tignon fabric worn by New Orleans women was imported and took several processes to achieve its typical appearance. The shipping of cotton was controlled by the British who sent cotton to the town of Pakaya in the British controlled colony of India. Once in Pakaya, the cotton was spun into cloth and the cloth was then sent to the nearby town of Madras to be dyed with banana tree fibers. The cloth could also be sent to Saint Domingue, Haiti to be dyed or decorated. After dying, the finished cloth was transported to the French West Indies where it made its way to the colonies. This fabric arrived either in one large cloth to be separated depending on how much fabric the buyer wanted or came already separated into individual squares for traditional tignons. The Madras print is very prevalent to this day and is referred to using the word Madras or just plaid, but all patterns originate from the same fabric dyes and decorations [4] . The typical fabric was cotton broadcloth, calico, or muslin, according to Trevigne, and while silks and other expensive fabrics were popular they were not preferred for tignon tying as silk would slide off the head and was difficult to tie. For her demonstrations, Trevigne provides those who wish to learn how to tie tignons with several cloth options, ranging from solid colors to wild prints, but the cloth is always a sturdy cotton that prevents the fabric from slipping.

Tignon “Law”

In terms of the “tignon law,” women of color were allegedly forced to wear the tignon headscarf to set them apart from white women in New Orleans. Contrary to popular belief though, this “tignon law” was no law at all. In the late 1780s, Spanish governor Esteban Miró created the Edict of Good Government, an edict outlining the guidelines for creating a successful colony.Trevigne suggests that Miró felt that women’s dress had become so elaborate and women of color had gained so much attention that he felt he needed to find a way to distinguish women of color and attempt to downplay their beauty to prevent free white men from pursuing these women. Due to the increase of relations between slave women and white men, it became difficult to distinguish between women of color and white, European women. Miro’s edict stated,

_“The idleness of the free negro and quadroon women is very detrimental, and those who abandon themselves to same, is because they subsist from the product of their licentious life without abstaining from carnal pleasures, for which I admonish them to drop all communication and intercourse of vice, and go back to work, with the understanding that I will be suspicious of their indecent conduct, by the extravagant luxury in their dressing which already is excessive, and this only circumstance will compel me to investigate the customs of those who will present themselves in this manner. The distinction which exists in the hair dressing of the colored people, from the others, is necessary for same to subsist, and order the quadroon and negro women, wear feathers, nor curls in their hair, combing same flat or covering it with a handkerchief if it is combed high as was formerly the custom.” [5] _

While this edict served as more of a guideline for the city of New Orleans, we can assume that Miro intended these guidelines to be followed as laws as he mentions punishment “with all the severity of the law” [6] later in the edict. The question we now face, according to Trevigne, is what happened to women who left their hair uncovered? Would these women be severely punished as Miro suggests? We also have to ask who considered herself white or creole or African American? After examining many portraits of women in New Orleans and surrounding areas during the eighteenth century, we see that the tignon “law” or guideline was not strictly followed and in fact became a trend for white women.

Deeper Meaning

The tignon style of wrap had been around for much longer than the Edict of Good Government. Wrapping the hair in various cloths has been occurring for a long time and depending on where one lived or social status, the wrap could carry various meanings. As Trevigne says, “you can never tie a tignon the same way; you let the fabric dictate it” [7] Tignons were typically referred to at the time as mouchoirs de tete, which means square piece of cloth, or simply a kerchief. According to a drawing of various Haitian women wearing tetes, as they called their head covering, the tying of your tignon carried various meanings. For example, a tete with one knot carried a ceremonial meaning while a tete with three knots might mean, “my heart is taken” [8] In terms of the tignon displaying social status, Trevigne asserts that the size of the tignon and quality of fabric determined a woman’s status. The Ellsworth Woodard etching “Black Woman in a Tignon,” carries the negative connotation of the tignon as the woman pictured wears a bandana tied closely to her head denoting that this woman works outside and wears this bandana out of necessity as opposed to the larger and higher tignon worn because of the fashion statement by the master’s mistress or other women in the house [9] The method of wrapping the tignon also came from various places including the candomble from Brazil, the tete from Haiti, and the original gede from various countries in Africa.

Conclusion

The tignon of Colonial Louisiana was meant to set African American women apart and put them down, but it did just the opposite. Many women today still wear tignons as a tribute to their heritage in addition to the fashion statement it makes. Trevigne especially advocates the use of the tignon as it highlights the face by pulling the hair back and her demonstrations make women of all backgrounds feel beautiful and empowered. The tignon can now be seen as a trend that transcended the colonial age to become a popular hairstyle of modern New Orleans.

Works Cited

- Barbara Trevigne (Tignon and Cultural Historian, New Orleans), Interviewed by Jeila Martin Kershaw, February 2013.

- Barbara Trevigne (Tignon and Cultural Historian, New Orleans), Interviewed by Jeila Martin Kershaw, February 2013.

- Barbara Trevigne (Tignon and Cultural Historian, New Orleans), Interviewed by Jeila Martin Kershaw, February 2013.

- Barbara Trevigne (Tignon and Cultural Historian, New Orleans), Interviewed by Jeila Martin Kershaw, February 2013.

- Edict of Good Government, July 2, 1784, Digest of the Acts and Deliberations of the Cabildo, Laws, Volume 1, Book 3, p. 105-112, Louisiana Division/City Archives, New Orleans Public Library, 219 Loyola Ave., New Orleans, LA 70112.

- Edict of Good Government, July 2, 1784, Digest of the Acts and Deliberations of the Cabildo, Laws, Volume 1, Book 3, p. 105-112, Louisiana Division/City Archives, New Orleans Public Library, 219 Loyola Ave., New Orleans, LA 70112.

- Barbara Trevigne (Tignon and Cultural Historian, New Orleans), Interviewed by Jeila Martin Kershaw, February 2013.

- Barbara Trevigne (Tignon and Cultural Historian, New Orleans), Interviewed by Jeila Martin Kershaw, February 2013.

- Barbara Trevigne (Tignon and Cultural Historian, New Orleans), Interviewed by Jeila Martin Kershaw, February 2013.

>via: http://medianola.org/discover/place/945/Tignon-of-Colonial-Louisiana-