June 5 2014

Most history students never learn that even Martin Luther King Jr.—arguably history’s greatest spokesperson on behalf of nonviolence—had armed guards stationed outside of his home and a pistol tucked in his sofa in 1955 when he emerged as the leader of the bus boycott in Montgomery, Ala.

But he did.

As time went on, he came to trust in the philosophy of nonviolence in his personal life as much as he believed in its power politically, and eventually got rid of both the guards and guns. At some point, though, we glossed over this complexity and began to think of nonviolence as preordained and as a natural outgrowth of the movement.

We don’t teach our children about the training civil rights activists had to endure in order to prepare their minds and bodies for nonviolent protests. And we don’t often think about how the movement functioned in rural places, far from the glare of the spotlights of network news cameras. Outside of the national gaze, what might check the violence of white segregationists who resisted every attempt by black citizens to assert their right to vote and to organize politically? How did the movement work in the face of the violence in rural Union County, N.C.; Lowndes County, Ala.; or Sunflower County, Miss.?

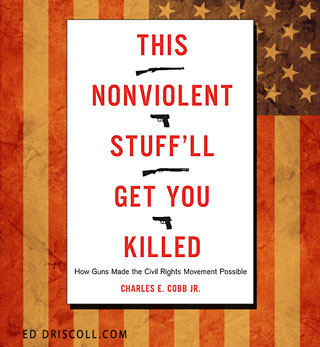

That’s the story masterfully told by Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee field secretary and now journalist Charles Cobb in his challenging and important new narrative, This Nonviolent Stuff’ll Get You Killed: How Guns Made the Civil Rights Movement Possible, which adds to a growing list of important histories that expand what we know about the way organizing had to work in rural communities.

Historically, black citizens had to arm themselves; they hunted and, more important, they maintained their homes and the safety of their families against anyone who might challenge it. After all, black families who owned land, ran businesses or sought an education for their children did so in spite of Southern white supremacists who often employed violence to try to assert superiority over and displeasure with any sign of black achievement.

It didn’t mean that most black Southerners were violent or did not believe in the tactical power of nonviolence grounded in Christian ethics. But Cobb’s narrative reminds us that many black Southerners believed in both nonviolence and self-defense, and they didn’t see them as ideas that had to be at odds with each other.

When I think of how these two ideas dovetailed in the lives of black Southerners, I think about my great-uncle Obie Duncan. Uncle Obie could best be described as a rough-and-tumble man. He and my grandfather grew up in rural Georgia, the sons of a sharecropping father who was forced to sneak away with his family at night from a landowner who planned to keep the family in continuous debt by cheating them out of their share of the crops year after year.

Uncle Obie and my grandfather hoboed on trains as teenagers looking for work. They were self-taught carpenters who built their own homes from the ground up. Uncle Obie was also a veteran of World War II and generally didn’t have a lot of patience for the racism of the South after he returned from the war. Healthy until the day he died, he was in his 90s when his heart simply gave out one day.

At his funeral, his pastor lauded the Christianity and charity of Uncle Obie. He talked about the way he shared the food he raised in his fields with his neighbors—of all races—the ways he helped those who were sick and shut-in and his devotion to his church and family. At the end of the service, I was left thinking that the pastor had failed to capture Uncle Obie’s hard and resilient side. But when we returned to his home after the funeral and went to the bedroom to change clothes, we found a loaded shotgun behind the door. My mother and I both smiled and laughed—that was Uncle Obie. Like many black Southerners of this generation who kept the shotgun behind the door, my uncle had Christian faith and a faith in self-defense.

It’s that ethos that Cobb recaptures with stories of black Southerners who worked behind the scenes to protect civil rights activists who engaged in nonviolent protest, the conversations that student organizers had with local black Southerners about the dilemma of whether or not to “bring their pistol” when they went to try to register to vote, and grassroots cooperation between both sides that quietly undergirded the movement in the rural South.

Cobb invokes the language of “stand your ground” here in an instructive and provocative way, forcing us to learn that along with pushing for constitutional rights promised in the 14th and 15th amendments, black Southerners, quietly, were often also fighting for their Second Amendment rights, too.

+++++++++++++++++

Blair L.M. Kelley is an associate professor of history at North Carolina State University and the author of the award-winning book Right to Ride: Streetcar Boycotts and African American Citizenship in the Era of Plessy v. Ferguson. Follow her on Twitter.

Like The Root on Facebook. Follow us on Twitter.

__________________________

Jun 12th 2014

Q&A: Charles Cobb

Guns n’ Rosa

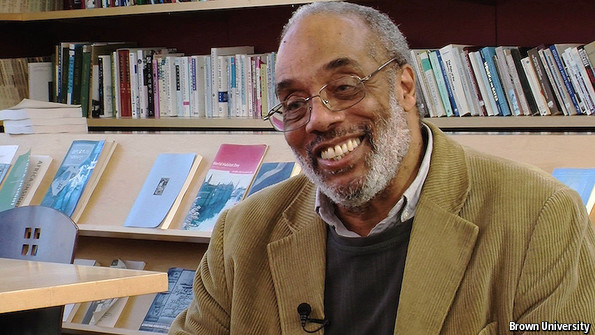

CHARLES COBB is a veteran of the Southern civil-rights movement, who decided to leave college in the 1960s to work full-time in the Student Nonviolent Co-ordinating Committee (SNCC), one of the movement’s key organisations. As a journalist and visiting professor at Brown University, he has been documenting the untold stories of the civil-rights movement in an effort to address what he describes as the reductionist history of black resistance in America.

His latest book, “This Nonviolent Stuff’ll Get You Killed”, details how armed self-defence and non-violent protest were complementary tactics in the effort to secure civil rights for black Americans.

What was the impetus behind the book?

My very strong feeling as someone involved in the Southern freedom movement, is that the story of the freedom struggle in the South has been incompletely told. It’s disconnected from real history and reduced to simplistic stories. As Julian Bond, who was also involved in the Student Nonviolent Co-ordinating Committee, said to me, “The whole narrative of the civil-rights movement has been reduced to Rosa [Parks] sat down, Martin [Luther King Jr.] stood up, and white Americans saved the day.” And Stokely Carmichael has been reduced to “black power” while Martin Luther King Jr. has been reduced to the “I Have a Dream” speech. So I have this concern about the accuracy of an American freedom struggle. For example, why was a freedom struggle necessary? To understand this, you have to go all the way back to slavery, along with the subsequent laws and attitudes that emerged from this system of oppression. This helps us understand the pattern of rebellion by black Americans over the centuries.

Why do you think the history of the civil-rights movement and southern freedom struggle is so incomplete?

Because to take an honest look at history requires us to be challenged. And it’s easier to deal with the uncomfortable history of racism in America when it’s reduced to the idea of a “noble non-violent movement”. It’s easier to view Dr King as an icon even though he was a very radical individual.

Further, I’ve been a working reporter most of my life, and I have found that news is shaped more by what’s left out than by any bias of the reporter. And the views about the southern freedom movement is shaped significantly by what’s left out—such as the contributions of SNCC, the Congress of Racial Equality and even the Southern Christian Leadership Council. Of course, we know about Dr King. I was part of SNCC—and I’ve seen how the contributions of the young people in the 1960s and these other organisations are often left out of popular discourse. I think the upsurge of student protests in the 1960s and the decisions of students such as myself to leave school and work at the grassroots level radically changed the direction of the southern freedom movement—though this is largely ignored in contemporary discussions.

Can you tell me about the title?

The title is a shortened version of what a Mississippi farmer told Dr King in 1964: “This non-violent stuff ain’t no good Dr King; it will get you killed.” While this was much too long for a title, it certainly helps illustrate the attitudes about resistance among black people in the South.

You described the experience of black Americans in the South as one of terror. Can you elaborate on this idea of terrorism in America’s history?

Well, organisations such as the Ku Klux Klan were very much terror organisations. When they bombed the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama, and killed four little girls, that was a terrorist act. And as a journalist, I understand that in the aftermath of September 11th, the idea of terrorism resonates in the public mind more than ever before. But those of us in SNCC and the southern freedom movement, we always understood the actions of white supremacy groups as terrorist attacks, which necessitated self-defence.

Can you help resolve what might appear to be a philosophical tension between the ideas of a non-violent movement and armed resistance?

They may appear that way philosophically. But I don’t subscribe to the notion that there is a dichotomy between non-violent protest and armed self-defence, and neither did the people of the South. They sometimes operated in tension; but more often operated in tandem. People didn’t describe themselves as “non-violent” or “violent”. People of the South talked about being “in the movement”. And they made very practical and hardheaded decisions. Ms Fannie Lou Hamer, who was a leader in the voting-rights drive in Mississippi, would say that she had shotguns throughout her home—and “anyone who throws dynamite on my porch won’t write his momma again.” So she didn’t see any contradiction between that stance and being part of a non-violent movement. The fundamental question that people asked themselves was “what makes the most practical sense”. In some instances, grabbing a gun to protect oneself made the most sense. Other times, going to protest at the county courthouse was more appropriate.

It’s also important to understand there is a very real difference between non-violent protest and armed self-defence, particularly in the rural south. There is also a difference between being in an urban setting and the rural south. When you are protesting in a city or sitting in at lunch counters, you are choosing whether to be a target of potential opposition. When you are in the rural areas, the punishment and attacks are collective—blowing up churches or killing people who had no connection to the movement was not uncommon. So the choices you had to make were very different. Very few people believed in non-violence as a way of life—with the exception of maybe Dr King or Reverend James Lawson, who helped organise students in Nashville, Tennessee. Most of us accepted non-violence as a tactic that seemed to work, rather than a way of life.

Do you think that, philosophically or morally, the power of non-violent resistance was greater than the power of the gun?

You could argue that, in a sense. But we were really focused on non-violence as a tactic. For example, who could be opposed to those well-dressed students sitting at lunch counters trying to get a hamburger and a cup of coffee? It really appealed to the sensibilities of people who may not have otherwise embraced civil rights—at least in the cities. However, in the rural areas, there’s really no place to sit in. In the South, people didn’t want hamburgers but rather more control over their own lives.

What do you think dictated the decision to choose one approach over the other?

It’s purely a question of practicality. You couldn’t mount an armed attack on the county courthouse. But you could on the other hand mount a non-violent attack on the county courthouse by attempting to register to vote. These are the practical considerations. The use of guns wasn’t about armed attack—but rather the human impulse to protect oneself and one’s family.

As a veteran of the civil-rights movement, what do you see as its modern-day struggle?

In the South, we thought of ourselves as being involved in the freedom movement. So if we think about the freedom movement, there are a few major issues that remain with us today. Can you get quality education is public schools? This issue was not decided in the 1960s. If you are not educated, how can you meaningfully participate in your civil rights? The second issue is the steady erosion of civil liberties in the name of national security. Finally, the last freedom-rights issue in my mind centres around money: who has it, how do they use it, and what does this mean for the direction of country?

>via: http://www.economist.com/blogs/prospero/2014/06/qa-charles-cobb