February 20, 2013

Zena el Khalil:

Unsanctioned Writing

from the Middle East

Nowhere Near a Damn Rainbow: Unsanctioned Writing from the Middle East is an anthology of work from 31 poets who are part of the poetry collective known as the Poeticians.

Sampsonia Way asked Hind Shoufani, founder of the Poeticians and curator of the book, to pick eight writers to be interviewed via email. In this series we present those poets’ voices and publish a poem from each.

The writer profiled in our sixth installment is Zena el Khalil, a poet currently based in Beirut, who allowed us to publish her poem “Dear Firas.”

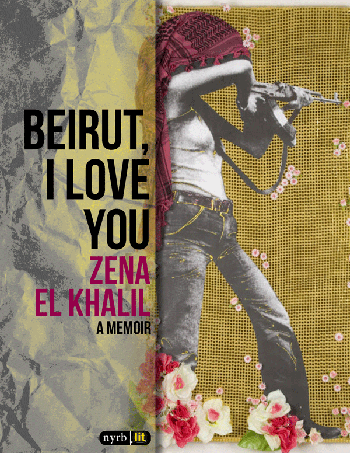

Poet Zena el Khalil was born in London and has lived in Lagos, London, New York, Turin, and Beirut. Her most notable publication is a memoir titled Beirut, I Love You, first published in 2009. It has been translated into multiple languages and adapted into a feature film, currently in production. Throughout the 2006 Israeli invasion of Lebanon, Khalil kept a blog called BeirutUpdate that was featured on CNN, BBC, and The Guardian. In 2008 Khalil was invited to speak at the Nobel Peace Prize Center in Oslo and in 2012 she was made a TED fellow. She currently works as a visual artist, cultural activist, and part-time publisher with xanadu* in Beirut. Additional material can be found here and here.

“Dear Firas” is about the relationship one woman has with Beirut, described through her various romances. The city is in the midst of change, reconciling a war and its consequences. Why did you pick that topic, and why did you pick the format of a love letter?

Beirut is the topic of most of my work, in both art and literature. We have a love/hate relationship—the city is alive and hard to avoid. It naturally comes up in everything I say, do, and think, whether I like it or not.

As for the second part of the question, to be honest, it involved a lot of wine and a lot of nostalgia. Something I regret is not being able to maintain good relationships with my ex-boyfriends. It’s normal to miss someone you once loved so deeply. “Dear Firas” had to be a love letter because it included bits and pieces of memories of everyone I’ve ever loved in Beirut. Moments, fragments, things we said, stuff we promised…. As the city changed, I tried hard to hang on to my lovers, but Beirut pushed and pulled and tore until I had to let go. They were very emotional years and “Dear Firas” immortalizes that part of my youth and the rebirth of Beirut after the civil war.

You have lived in London, New York City, and Beirut, among other places. As you’ve said, Beirut is also a topic in most of your work; how do you define yourself in terms of nationality?

I’m a citizen of Planet Earth. Where I lay my head is home. And whom I share my wine with, is family.

Why is the Poeticians important to you?

In this part of the world, great ideas come and go very quickly. We have a problem with commitment because things change so fast here. We live each day as if there is no tomorrow, so planning for the future becomes very challenging. The Poeticians is important to me first and foremost because of its quality and consistency…. And it’s growing.

Xanadu*, the art collective and press I co-founded in 2001, provides young and/or underrepresented artists and writers with a launch pad to jump from. A big part of my criteria in choosing whom to work with depends on their own personal initiatives—how far they are willing to get involved in the whole process, and how serious they are about their careers. As such, working with the Poeticians was a no-brainer for me. They are exceptionally creative and as professional as poets get.

Nowhere Near A Damn Rainbow highlights that it’s an uncensored book of “unsanctioned” writing. How have you benefited from being in an uncensored collection?

The Middle East is going through some serious changes right now and if we are to be part of that change, we must be able to speak freely. If we are to contribute, we must be able to say it as it is; the good, the bad, and the ugly. A lot of these poems are historic—they are about here and now. They are edgy, political, and opinionated.

The benefit of all this has been that, through this open platform, we attracted amazing writers who wrote with no limits for this collection. It’s an honor to have so many of them all under one title.

Can you talk about freedom of speech in Lebanon?

Lebanon is a very open country and we do have freedom of speech. We have more TV stations and newspapers than I can count. Everyone is entitled to say what they want. The only subjects that are considered taboo are Israel and pornography. From time to time, religious leaders may ban a book like The Da Vinci Code. Also during political conflicts, journalists have been assassinated. For example, after our prime minister was assassinated in 2005, a string of journalists criticizing Syria were targeted. But in general, it is the type of country where a blonde bombshell can prance around, half naked in a bikini, carrying a semi automatic weapon, and then decide to run for elections.

What misunderstandings does the West have about Middle Eastern literature?

There is no misunderstanding because there is nothing to misunderstand. There is not enough of our work out there for anyone to pass judgment on. The whole world knows about Khalil Gibran and possibly One Thousand and One Nights, but that’s pretty much where it stops.

But this book isn’t about breaking stereotypes. I feel like we’re genuinely creating. We are part of a movement of individuals who are determined to craft their independent stories and challenge the status quo. There are generations upon generations of incredible Middle Eastern literature, but so little of it has been translated, and therein lies the problem. Most of the Poeticians write in English, simply because it’s the language they are most comfortable with (though most of us are trilingual), and this provides a natural bridge to the rest of the world.

What are you working on now?

Beirut, I Love You the feature film.

DEAR FIRAS

excerpted from “Beirut, I Love You”

Dear Firas,

Do you remember the time you almost jumped

out your window? It was during the winter

solstice. You called me and told me you were

sitting on your windowsill and that life no

longer had any meaning. Your father was

divorcing your mother and you could not stand

to see her humiliated. Many years later she

died of a broken heart. She never recovered.

Stress brings on cancer.

It was winter and you were sitting on your

windowsill. I drove over to your house like a

crazed woman. It felt like a Scorsese flick. The

streets of Beirut were wet with rain. The traffic

lights seemed to be on a permanent red. Not

that it mattered because I crossed them all.

Not that it mattered because we don’t have

traffic police here. Not that it mattered, but I

never understood why they put in the lights

in the first place. Are they trying to fool the

western tourists who come here to visit?

Do they want them to feel safe and encourage

more tourists to visit simply because we have

traffic lights? I remember when we didn’t. Not

much had changed with them.

Driving to your house like a mad woman, I

remember the reflection of tragic red lights on

the wet wet streets. It looked like blood. Your

blood. The blood of Qana. Where Jesus turned

water into wine. Where the Israelis blew up

about a hundred women and children in what

was called Operation Grapes of Wrath.

water

wine

blood

rain

traffic lights

I remember how small your feet looked as

I stood under your apartment building. I

thought about how ridiculous you would look

if you died barefooted in your boxers. I was not

going to let you die like this.

Did I save you that night because I loved you

or because I wanted to save you? The answer

presented itself to me months later when you

finally had the courage to stand up and leave

me.

You were tired of being loved.

And I am just a Mother Teresa when it comes

to distraught Beiruti men. I, who should be

wild and boundless, find myself in the chronic

comfort of troubled men. I, who should always

be throwing my shoes out of windows, find

myself consoling weak and frantic men. I,

who should be walking the nights in tight red

dresses, find myself cradling balding men as

they weep in my arms.

It is really the men who deserve to cry in

this city. All this pressure they are constantly

under. Here in the black hole sun of the Middle

East, how do you show that you have become

a man. How do you cross to the other side?

What do you have to do to present yourself

as worthy of being called a man. What if you can’t

fight? What if you can’t wheel and deal? What

if you just want to dance?

I love you. I will always love you for not being

brave enough to tell me that I was killing you.

Once, you asked me to grant you one night.

And when I did, you cried in my arms the

whole night through. You stayed in my bed. You

helped me throw shoes at the night drummer.

We made love during the holy month. We

drank wine. We recited Rumi and Al Mutanabi.

I pretended to be Shahrazade. We climbed

up on the roof and watched the sun come

up. We drank more wine and vowed that we

would always stay pure. That we would always

do what our hearts commanded of us. That

we would walk the tightrope and never fall.

That neither war, nor bombs, nor unfriendly

neighbors would ever break our spirit. That

love was king and I was your queen. That

we would run through wet laundry under

the desert sun. That every moment would

be precious. That every moment would give

birth to a new one. That life could be what we

wanted it to be. That there would be no more

planes breaking the sound barrier. That there

would be no more assassinations. That there

would be no restrictions. No restrictions to

love. No religion, but love. That we would drive

at high speeds and never crash. That we would

drink and never pass out. That the stars would

always guide us. That the sound of prayer from

the mosque down the street was the signal for

lovemaking. That climaxes would be reached

before the call to prayer was over. That we

would live forever, like the stencils of martyred

militiamen on tattered Beirut walls. Like stray

cats who always found their chicken bones.

Like the sea, the endless blue. Like your eyes,

an endless forever. Like bitter coffee, I swore

never to write about. Like war… that will

never end. We were at war, you and I. It was

us against reality. It was our madness, against

black veiled nights. It was our hearts, against

bullet-riddled walls. It was our souls, against

the nature of man. It was love, when there

should have been death. It was light, when the

sea went to sleep. It was warmth, when Beirut

was shot dead.

I never thought I could live it without you. I

never thought I could find Beirut again after

you left me.

But I did.

Because as long as there are men who need to

be loved, Beirut will open her arms to me and

present me with her next victim.

I love you. I always loved each and every one of

you. Because you all brought me Beirut. In her

full glory. In her madness unrestrained.

She shot my heart over and over. It was always

a surprise. It was always an end and a new

beginning. The morning after a bottle of vodka.

A rebirth. Drinking water after eating ice

cream. The chills of a great song. The panic

attack after smoking hash. The ghosts in the

tunnels. The thousands, 17,000 people to be

exact, who are still declared missing. It is the

undiscovered mass graves. It is the hanging

that will follow. It is a hymen repair operation.

It is the addiction for the next bomb. It is

orange lipstick and grapevine shelters. It is

riding a bicycle when you should be choosing

a husband. It is wearing a wedding dress

and running through the streets of Beirut.

It is discovering religion through sex. It is

discovering music through war. It is eating

processed cheese on round flat bread. It is

drinking whisky with three ices exactly.

It is crying while you sleep.

It is vomiting black flies.

It is killing while you cum.

Love,

z.