HOW I BECAME THE WALRUS

1.

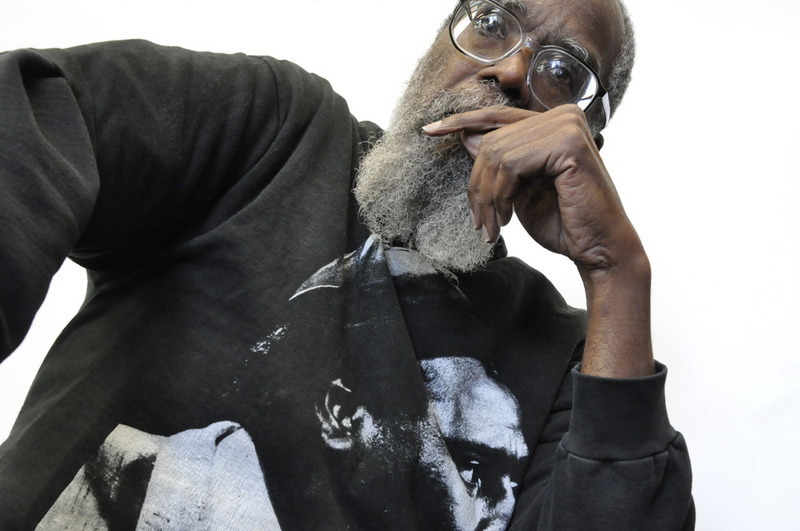

Recently on Twitter, a student called me a walrus [Darian said my teacher(Kalamu) looks like a big ass walrus with one tooth. Smh cuz he right.].

a big old, one-tooth walrus. I smiled. That was a nice succinct image: something both strange and known, mysterious and by implication “knowing,” as in: I knew something and the observers knew I knew something without necessarily knowing what it was I knew or whether what I knew was valuable (to me, to them, or to anyone). A walrus.

2.

I remember when I consciously became me, i.e. when I made the intellectual decision to pursue being “me,” which after all meant not so much deciding “who am i?” but rather really meant, without either self-flattery or sentimentality, identifying “who have I been”: what made me, who made me, how family life and growing up where I grew up shaped me and how I responded to the shaping, like how certain tree branches made better bows that others and how to know when you had a good bow, a stretch of wood that was limber enough to bend but resistant enough to snap back and power the arrow where you wanted the arrow to go, as far as you needed the projectile to fly and with as much force as you need the missile to hit the intended target, like that, and then after identifying the antecedents, i.e. all the forces and influences that shaped me, then the really crucial part was deciding who I wanted to make me be

Who? Given the material that was me, who would I make me be/come? Hence, I was both the sculptor and the piece of wood or metal, or the lump of clay, except my material had a mind and part of my mind wanted to be what I was, while another part of my will wanted to be something else, and the most fierce battle was always internal, always the struggle to stop being who I was and give birth to who I wanted to be

3.

another student responded [I remember ribbin his funky az].

Reminder: don’t take yourself too seriously.

4.

I was always overweight as a child, sometimes slightly, a few moments grossly, but normally always a little more so than those around me.

Being different always makes a difference.

5.

The moment I consciously decided to be me was precisely the moment I decided not to be someone else.

I was walking quickly thru the chill toward the dorm door, a walk I would make at least a couple of hundred times more, even trampling through snow. I was seventeen. Snow was new to me. Just starting college. I’m from New Orleans, a city on the river, near the mouth of the Mississippi; a place where it is perpetually green, seldom snows, and even in winter grass grows. I was going to school in Northfield, Minnesota, not too far from where the Mississippi river starts its southward flow. And as I reached for the handle on the door, which was mostly super thick glass with a heavy metal frame, I saw a reflection of myself.

On the back of one of his early Columbia albums, I believe it was Miles Ahead although it could have been Porgy&Bess, Miles had his sweater thrown over his back with the arms of the sweater tied around his neck. Cool ass miles. I liked that. (You can understand how that iconic figure danced in the stunted style consciousness of the southern butterball that was me.) So, on my own for the first time, with no parent to correct me when I made whatever I considered to be hip sartorial decisions; no questioning why you wearing “that” whatever color or cut that particular clothing happened to be; no one to tell me what to put on or what to take off; in my mis-shaped budding self-development, I had my sweater thrown casually (or so I hoped the thing appeared casual)—you know I never could wear a sweater loosely around my middle with the arms tied dangling from my waist, my waist was too big and my arms too short for that—and, of course, I had the cotton sleeves tied around my neck, and sort of half-hoped, half-thought of myself as Miles without a horn.

Which was when I saw the reflection. I wasn’t Miles. But more importantly, I also recognized that the reflection wasn’t “me” either. My reflection showed me a fake, a not very good imposter, failing to be both me and failing to be Miles.

And in one of my most lucid and unforgettable moments over this sixty-some lifetime, I let the handle go, yanked the sweater arms from around my neck, gathered up the sweater into my left hand, reached out and opened the door with my right. I had said to myself: that’s not me.

6.

Me trying to be what I am not, is not me. I wanted to be an authentic me more than I wanted to be a look-like someone else, even someone else whom, for whatever reason, I admired.

7.

the first actual life-step in becoming ourselves (i.e. the first doing as opposed to the first thinking about doing) is to recognize what we are not and consciously step away from whatever that is, whatever behavior, affectations, gestures, way of talking, whatever.

A baby has to learn that the self is not someone else, not the mother whom you love to snuggle up to; not the blanket, the red-stripped ball, the stuffed animal, the bottle, none of that is you.

Not all the pictures that are presented to us of what we ought to be or what we desire to be; not the movie actors with whom we are smitten, or of whom we are jealous or envious, or whatever; not the entertainment stars, the musicians and athletes. Moreover, if you are not actually them, they are not you. That social equation is axiomatic, you are not someone else and someone else is not you.

And here, of course is where it gets tricky, because here is where desire enters the equation and the capitalist manipulation of our minds in America. In America we are taught we can be anyone we want to be.

And that is just not true.

Sure, we can be/come a lot of things but not “anything” we desire, especially given how our desires are so easily manipulated, or as George Clinton in one of his more perceptive moments (he has had more than a few moments of enormous clarity mated to an ability to pithily verbalize the insights gained from clarity), anyway, what uncle George said was: mind your wants because someone wants your mind.

Someone wants your mind. Why?

Why do we want to control the minds of others?

The Last Poets said, the white man’s got a god complex. Is there an innate human desire to control others? I don’t think so. Instead I think there is an innate human desire to control, how that desire is manifested is the crucial question. Some people want to control others. Some people work really, really hard at self control. Other people focus on controlling things: a juggler practicing at keeping thirteen navel oranges or brown chicken eggs rotating through the air without dropping any of them. Artists honing their craft so they can manipulate their mediums and their instruments in order to produce artistic work that is a striking creation.

Which all, I guess, brings us back to the god complex: the human desire for control can also find outlet as the human desire to create. With our people, this desire tends to morph into spontaneous, artistic expression regardless of what we’re doing. Creating beauty and goodness on the fly, in the moment, with whatever is available. Like Stevie said: you gots to work with what you got.

What did I want to control, want to create? My question, and at one level or another, the question for everyone is: who do I need to become in order to do what I want to do?

8.

The only exception to my overweight years on earth was for about three years during the mid-seventies when my diet and exercise regime was so fierce I looked like a shrunkened me. I remember my mother telling me I had lost enough weight, to stop. I was running five miles a day, a strict vegetarian (including no milk or milk products), routinely working 15 or 16 hours in every 24, plus listening to music and engaging in all kinds of political activity literally all over the world.

My passport picture from then makes me look like a refugee from the Congo who had been a guerilla soldier upcountry in the bush.

My clothes looked like they were hand-me downs from an elder uncle several sizes larger than me.

I had the gawky, elongated stature of a giraffe.

9.

Those of us born on the margins of society, whatever may define our marginality, it could be weight, it could be race, it could be religious beliefs, it could be gender, sexuality, whatever, those of us born on the margins of our society have both a challenge and an opportunity.

For us, the outsiders, the question of self-identity (which is always simultaneously a question of recognizing who we are and deciding who we want to become), for us identity is invariably a choice between assimilation and iconoclasm, either conform to the norm, which by nature we are not, or resist our society’s normative and create our own personal norm. Or as Charlie Mingus accurately called the state of desired existence: myself when I am real.

Like Thelonious Monk, Duke Ellington, Pops, Trane, so forth and so on. To be ourselves invariably for those of us lucky enough to be both born on the margins but reared in a society of plenty, a society that can support its citizens both materially and spiritually (whether the society does or does not do so is another question, I’m saying instead that the society has enough water, enough food, enough open space and green space in both the raw material sense as well as in the intellectual and spiritual sense) plus enough so-called weird people so that there can be a community of weirdoes, a society within which one can strike out on one’s own but at the same time find like-minded individuals, i.e. forge a sub-culture, a movement, a self-identifying group or organization or club or social society.

In New Orleans we have bands of musicians; Mardi Gras Indians; social, aid & pleasure clubs.

My mother belonged to a bridge club (most of the members were school teachers) called the OGG’s. They took to the grave with them the meaning of the initials.

When I was in junior high school we had “the fun club,” a grouping of us who would pool our money and throw a Sunday afternoon party each month rotating like a full moon rising at the houses of our different members.

And, of course, from high school on I had political organizations, beginning in 10th grade with the NAACP Youth Council and reaching its apogee in the seventies and early eighties with our pan-afrikan nationalist organization Ahidiana, which ran an independent school (pre-school thru 4th grade), a book store, a printing press, a performance group (the Essence of LIfe), and over-arching political formations (ranging from an annual black woman’s conference to day-to-day community organizing around social issues, particularly police brutality and related social equality struggles against the status quo).

Later my social activity was a writers workshop, the last and most successful of which was the Nommo Literary Society.

The current and perhaps final of these social formations is Students at the Center, a writing program that functions in the New Orleans public high schools.

Which is where in 2011, well over a decade after I started in the fall of 1997, I daily teach young people on the cusp of adulthood, the time when they are most rebellious, least likely to take directions from an adult elder, and at the same time they are in a position to tremendously benefit from adults honestly sharing life experiences with them as these young people set out on their own self-determined paths.

10.

The trick is to guide by inference, by sharing learned life lessons and experiences, but staying out of the way, a long way out of the way. Not to befriend as much as push and boost. Push them out of their mental nests, pick them up when they fall, and throw them back up in the air, with but one simple instruction: fly.

I once admiringly wrote of the elders who preceded me: they made me strong enough and taught me how to run, but they never told me where to run to.

11.

For we elders, especially we male elders, we must always, always resist the urge to become sharks feeding on our youth, whether it’s basking in their easy applause and adulation, or more sinisterly physically consuming their youth in our own vain effort to hold on to youthful energy, intelligence, beauty.

We adults should be a sanctuary for youth, a safe place where the young can both explore and be themselves, seek and search for the selves they desire to become; experiment; fail and succeed; discover and get reinforcement; we should be foundation, but we can not be them, and we should love them at a distance.

I was lucky to have elder teachers who understood how to love me without seeking to be a peer friend, especially not a friend with benefits. But of course the beauty and innocence of youth is a hard temptation for old people to resist.

It’s hard not to be a shark when there is so much lovely flesh swimming nearby. Even harder not to set up aquariums for personal enjoyment. Not to collect favorite students within the prison of our personal delights.

Seems like life is a constant battle to socially do the right thing, to set a moral example of what a good person is: a human being who respects all other life forms and strives to leave the world better and more beautiful than when we were born.

12.

I am constantly learning, literally. I hear people say the cliché: learn something new every day. But in order to learn we must study, have a hunger to know what we don’t know, and teach what we do. I believe learning is not complete until we teach, either directly or by example.

13.

The walrus reads, studies life. A shark stalks, eats life. We can choose.

14.

I have decided to spend the last years of my life working with young people. That’s how I became a walrus.

—kalamu ya salaam