OCTOBER 15, 2012

Preview

‘Melvin & Jean: An American Story’

(Couple Hijacks Plane

To Escape Racial Oppression)

Looking over this year’s DOC NY festival, quite a bit I’d like to see, when the festival opens its doors on November 8(through the 15th), here in NYC.

Like this one… titled Melvin & Jean: An American Story.

The fascinating story goes… when Melvin and Jean McNair hijacked a plane from Detroit to Algeria in 1972 with their two babies on board, they called it an act of political resistance. The hijacking was also an act of desperation committed by two people in their early twenties who saw no other way to escape what they felt was the constant state of racial oppression in America. Living in Paris for forty years after the hijacking and unable to return to the US, Melvin and Jean are still coming to terms with their act of crime and its lifelong consequences.

Intrigued? I hope so.

Maia Wechsler is the film’s director.

This is a documentary film, but I think many of you would agree that this is a story that deserves the scripted narrative treatment. Just check out the 4-minute preview below:

__________________________

Saturday, August 10, 2013

Railey on flying the not-so-friendly skies of the ’70s

John Railey/Winston-Salem Journal

Oh for the early 1970s, when commercial flights were still fun.

When men with long sideburns and women with their hair in “permanents” still dressed up to fly. When you could stride through an airport, unhindered by security checks of your person or your Samsonite, and buy your ticket at the gate. When you could smoke on the plane if you wanted.

When some months, hijackings were happening almost once a week.

OK, not that fun.

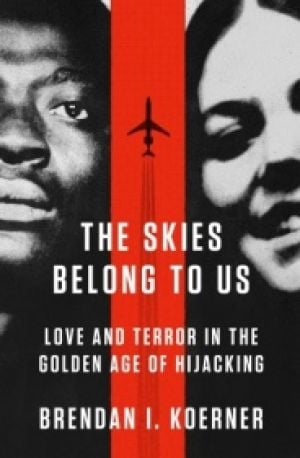

A new nonfiction book, “The Skies Belong to Us” by Brendan I. Koerner (Crown Publishers), captures well the terror and lunacy of those times when misfits, ranging from drunks to Vietnam War protesters, acted like bell-bottomed pirates.

Koerner concentrates on two hijackers: a black Vietnam vet, Roger Holder, and a white hippie chick, Cathy Kerkow, who were in love with each other and their kinda/maybe/sort of plan to protest the Vietnam War by hijacking a plane.

Koerner weaves in the tales of numerous other hijackers, including Triad natives Melvin and Jean McNair, who brought their two children along on their hijacking. And the plane they hijacked from Detroit just happened to be piloted by William May, who now lives in Winston-Salem.

“What are the odds?” May, 82, asked me last week. “I grew up here and so did they.”

A few years ago, May reunited with the McNairs an ocean away – a meeting he never would have imagined in the 1970s.

Back then, law-enforcement officers, and some politicians, wanted to take aggressive steps to stop the hijacking epidemic, mainly by requiring passengers to go through metal detectors before they boarded planes. The airlines successfully resisted, fearing that step would cost them business.

So hijackings occurred at an astounding rate. Several of the hijackers demanded millions of dollars, sending airline officials scrambling to banks to meet their demands, even as they rebuffed efforts by FBI agents to intercede, not wanting more airborne gunfire than the hijackings had already caused. In the meantime, stewardesses sometimes over-served passengers to the point that the passengers weren’t that helpful in identifying their hijackers.

Much of the money was eventually recovered, including from hijackers who parachuted out of jets. Many of the hijackers directed the planes to Cuba. Fidel Castrol let the American planes fly home, but often granted the hijackers refuge.

Holder wanted the plane he hijacked in June 1972 to go to North Vietnam. When he learned that wouldn’t work, he directed it to Algeria, where the Black Panthers had a stronghold, even though Holder and Kerkow had no connection to them. Along the way to Algeria, Holder smoked numerous joints, and he and Kerkow … well, let’s just say they joined the 30,000-feet club.

Holder and Kerkow were granted refuge in Algeria, with the Panthers. Algeria returned their ransom money to the U.S. government, rebuffing the Panthers’ attempts to claim it.

A couple of months later, the McNairs and their “hijacking family” from Detroit arrived in Algeria. As Koerner tells it:

The hijackers, all young African Americans who had been roommates for less than a year, had varied reasons for wanting to leave the United States. Melvin and Jean McNair, a married couple from North Carolina, were on the run from the Army. Melvin, a former star athlete at Winston-Salem State University, had become opposed to the Vietnam War while stationed in West Berlin, and he had deserted when ordered to fight in Southeast Asia … Joyce Tillerson, a childhood friend of the McNairs, had become radicalized while working odd jobs at Oberlin College, where she first encountered the works of Marcus Garvey and Malcolm X.

Melvin McNair was from Greensboro. His wife, who also attended Winston-Salem State, was from Winston-Salem. Tillerson was from the Triad, and her mother lived in Winston at the time of the hijacking. Tillerson brought her daughter along on the hijacking.

Holder and Kerkow eventually made their way to France. So did the McNairs and the rest of their “hijacking family.” In French courts, most of them were convicted, but, with credit for time served, did little prison time

By the mid-1970s, the hijacking climate had changed. More hijackings had turned violent. Even Castro began refusing to let hijackers stay in his country. American airlines finally stopped their resistance and put in those metal detectors.

Holder, who made his way back to America, died disillusioned and dissolute in 2011. His former accomplice and girlfriend, Kerkow, is missing in action, as is Tillerson. And the McNairs now operate an orphanage in France, Koerner writes.

May, the Winston-Salem pilot, reunited with the McNairs a few years ago in France at a filmmaker’s invitation. May told me the reunion was friendly, for the most part. But at one point during the filming, he said, he laid it on the line to Melvin McNair.

“I told him that was a very dangerous thing you guys did. If you were so disenchanted with the U.S., why didn’t you just leave, why did you hijack an airliner? They didn’t have a good answer for that.”