FRI SEP 13, 2013

History of the Maroons

by dopper0189, Black Kos Managing Editor

When runaway slaves banded together and subsisted independently they were called Maroons. On the Caribbean islands, runaway slaves formed bands and on some islands formed armed camps. Maroon communities faced great odds to survive against white attackers, obtain food for subsistence living, and to reproduce and increase their numbers. As the planters took over more land for crops, the Maroons began to vanish on the small islands.

Only on some of the larger islands were organized Maroon communities able to thrive by growing crops and hunting. Here they grew in number as more slaves escaped from plantations and joined their bands. Seeking to separate themselves from whites, the Maroons gained in power and amid increasing hostilities, they raided and pillaged plantations and harassed planters until the planters began to fear a mass slave revolt.

In the New World, as early as 1512, black slaves had escaped from Spanish and Portuguese owners and either joined indigenous peoples or eked out a living on their own. Slaves escaped frequently within the first generation of their arrival from Africa and often preserved their African languages and much of their culture and religion. African traditions include such things as the use of medicinal herbs together with special drums and dances when the herbs are administered to a sick person. Other African healing traditions and rites have survived through the centuries. The early Maroon communities were usually displaced.

The jungles around the Caribbean Sea offered food, shelter and isolation for the escaped slaves. Maroons survived by growing vegetables and hunting. They also originally raided plantations. During these attacks, the maroons would burn crops, steal livestock and tools, kill slavemasters, and invite other slaves to join their communities. Individual groups of Maroons often allied themselves with the local indigenous tribes and occasionally assimilated into these populations. Maroons/Marokons played an important role in the histories of Brazil, Suriname, Puerto Rico, Haiti, Dominican Republic, Cuba, and Jamaica. By 1700, Maroons had disappeared from the smaller islands. Survival was always difficult as the Maroons had to fight off attackers as well as attempt to grow food.

Maroon communities emerged in many places in the Caribbean, but none were seen as such a great threat to the British as the Jamaican Maroons. As early as 1655, runaway slaves had formed their own communities in inland Jamaica, and by the eighteenth century, Nanny Town and other villages began to fight for independent recognition.

Nanny Town was a village in the Blue Mountains of Portland Parish, north-eastern Jamaica, used as a stronghold for Maroons led by Granny Nanny; the town held out against repeated British attacks before being destroyed in 1734.

Granny Nanny was born in Ghana, West Africa, as a member of the Ashanti tribe, part of the Akan people. She was enslaved and brought to Jamaica. Experiencing the cruel treatment of slaves on the Jamaican plantations, she and her five brothers, Cudjoe, Accompong, Johnny, Cuffy and Quao decided to join the autonmous African community of Maroons. This community developed as many more slaves escaped the plantations and joined the Maroons.

Nanny’s family then made the decision to split up in order to be able to organize better resistance to the plantation economy across Jamaica than was possible if they stuck together. By 1720, Nanny and Quao had organized and gained control of a town of Maroons located in the Blue Mountains. It was around this time that the town was given the title of Nanny Town. Nanny town encompased more than 600 acres of land for the run away slaves to live as well as raise animals and grow crops. Due to the town being led by Nanny and Quao, it was organized very similar to a typical Ashanti tribe in Africa.

The Maroons were able to survive on the mountains by sending traders to the cities to exchange food for weapons and cloth. The Maroons were also known for raiding plantations for weapons and food, burning the plantation, and leading the slaves back to Nanny Town.

Nanny town was an excellent location for a stronghold due to it overlooking Stony River via a 900 foot ridge making a surprise attack by the British virtually impossible. The Maroons at Nanny town also organized look-outs for such an attack as well as designated warriors who could be summoned by the sound of a horn called an Abeng.

Granny Nanny was very adept at organizing plans to free slaves. Over the span of 50 years, Nanny has been credited with freeing over 800 slaves. Nanny also helped these slaves remain free and healthy due to her vast knowledge of herbs and her role as a spiritual leader. However as you could imagine, freeing slaves upset the British. Between 1728 and 1734, Nanny town was attacked by the British time and time again, but not once was it harmed. This was accomplished due to the Maroons being much more skilled in fighting in an area of high rainfall as well as disguising themselves as bushes and trees. The Maroons also utilized decoys to trick the British into a surprise attack. This was done by having non disguised Maroons run out into view of the British and then run in the direction of the fellow Maroons who were disguised, thus crushing the British time and time again.

Jamaican Maroons fought British colonists to a draw and eventually signed treaties in the 18th century that effectively freed them over 50 years before the abolition of the slave trade in 1807. To this day, the Jamaican Maroons are to a significant extent autonomous and separate from Jamaican society.

One of the most influential Maroons was François Mackandal, a houngan, or voodoo priest, who led a six year rebellion against the white plantation owners in Haiti that preceded the Haitian Revolution.

In Cuba, there were maroon communities in the mountains, where escaped slaves had joined refugee Taínos (The Native Americans of the Caribbean). Before roads were built into the mountains of Puerto Rico, heavy brush kept many escaped maroons hidden in the southwestern hills where many also intermarried with the natives. Escaped Africans sought refuge away from the coastal plantations of Ponce. Remnants of these communities remain to this day (2006) for example in Viñales, Cuba and Adjuntas, Puerto Rico.

In Cuba the maroon were the only signs of resistance to the colonial system for many years. one of the largest in Cuba was found in 1815 near Havana with more then 200 cabins living near the city. The leader of this community was named Ventura Sanchez, and after a brief maroon war in 1819 he was captured but had taken his own life in protest of his return to slavery. His head was taken to Baracoa where it was displayed in an iron cage at the entrance to the city.

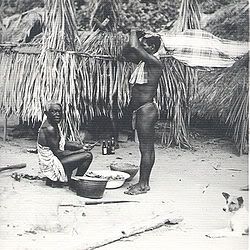

Cimarrones fiesta in Santiago, Cuba. Photo by Miguel RUBIERA JUSTIZ

The Spaniards lived in fear of maroons coming and raiding their towns, villages, and cities. Any news at all generated panic among plantations owners. The major concern of the Spanish colonial government was the persecution of maroons and the destruction of their palenques ( towns), even after the first half of the nineteenth century. The Island of Cuba and many of the other Spanish territories devoted much of their time to the suppression of rebellions and the destruction of these slave communities. However, these communities particularly in Cuba would also aid in the war of independence, and in 1868 Joined the Cuban Liberation Army.

Surinamese Maroons perform the fire dance during the annual celebration of Black People’s Day, in Paramaribo, Suriname.

In Suriname (on the northern coast of South America), which the Dutch took over in 1667, runaway slaves revolted and started to build their own villages from the end of the 17th century. As most of the plantations existed in the eastern part of the country, near the Commewijne and Marowijne rivers, the “Marronage” (literally: running away) took place along the river borders and sometimes across the borders of French Guyana. By 1740, Maroons had formed clans and felt strong enough to challenge the Dutch colonists, forcing them to sign peace treaties. On October 10, 1760, the Ndyuka signed such a treaty forged by Adyáko Benti Basiton or Boston, a former Jamaican slave who had learned to read and write and knew about the Jamaican treaty. The treaty is still important, as it defines the territorial rights of the Maroons in the gold-rich inlands of Suriname.

Body of Ndyuka Maroon child brought before a shaman, Suriname 1955

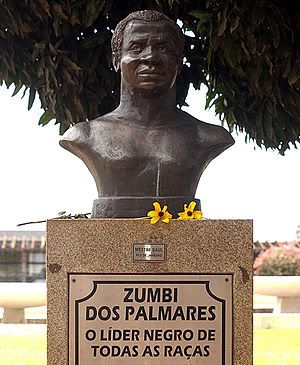

One of the best-known quilombos (maroon settlements) in Brazil was Palmares (the Palm Nation) which was founded in the early 17th century. At its height, it had a population of over 30,000 free people and was ruled by King Zumbi. Palmares maintained its independent existence for almost a hundred years until it was conquered by the Portuguese in 1694. During this time the vast majority of the enslaved Africans who were being brought to Pernambuco were from Angola, perhaps as many as 90%, and therefore it is no surprise that tradition, reported as early as 1671 related that its first founders were Angolan. This large number was primarily because the Portuguese used the colony of Angola as a major raiding base, and there was a close relationship between the holders of the contract of Angola, the governors of Angola, and the governors of Pernambuco.

Bust of Zumbi dos Palmares in Brasília.

An independent, self-sustaining kingdom, Palmares was vast and at its height hosted a population of over 30,000 free men, women and children. Although the “Guerra de Palmares” consistently calls the king Ganga Zumba, and translates his name as “Great Lord” other documents, including a letter addressed to the king written in 1678 refer to him as “Ganazumba” (which is consistent with a Kimbundu term ngana meaning “lord”).

After a particularly devastating attack by the captain Fernão Carrilho in 1676-7, Gana Zumba sent a letter to the Governor of Pernambuco asking for a peace. The governor responded by agreeing to pardon Gana Zumba and all his followers, on condition that they move to a position closer to the Portuguese settlements and return all enslaved Africans that had not been born in Palmares. Although Gana Zumba agreed to the terms, one of his more powerful leaders, Zumbi refused to accept the terms. According to a deposition made in 1692 by a Portuguese priest, Zumbi was born in Palmares in 1655, but was captured by Portuguese forces in a raid while still an infant. He was raised by the priest, and taught to read and write Portuguese and Latin. At age 15, however, Zumbi escaped and returned to Palmares. There he quickly won a reputation for military skill and bravery and was promoted to the leader of a large mocambo.

In a short time, Zumbi had organized a rebellion against Gana Zumba, who was styled as his uncle, and poisoned him. By 1679 the Portuguese were again sending military expeditions against Zumbi. Meanwhile, the sugar planters reneged on the agreement and re-enslaved many of Gana Zumba’s followers who had moved to the position closer to the coast.

Painting by Cándido López (1840—1902)

From 1680 to 1694, the Portuguese and Zumbi, now the new king of Angola Janga, waged an almost constant war of greater or lesser violence. The Portuguese government finally brought in the famed Portuguese military commanders Domingos Jorge Velho and Bernardo Vieira de Melo, who had made their reputation fighting Native American peoples in São Paulo and then in the São Francisco valley. The final assault against Palmares occurred in 1694. Cerca do Macaco, the main settlement, fell; and Zumbi was wounded. He eluded the Portuguese, but was betrayed, finally captured, and beheaded in 1695.

Zumbi’s brother continued resistance, but Palmares was ultimately destroyed, and Velho and his followers were given land grants in the territory of Angola Janga, which they occupied as a means of keeping the kingdom from being reconstituted. Palmares had been destroyed by a large army of Indians under the command of white and caboclo (white/Indian mixed-bloods) captains-of-war.

>via: http://www.dailykos.com/story/2013/09/13/1238232/-Black-Kos-Week-In-Review