Published: November 26, 2012

Some Scholars Reject

Dark Portrait of Jefferson

By JENNIFER SCHUESSLER

Henry Wiencek suspected he would be in for a rough ride when “Master of the Mountain: Thomas Jefferson and His Slaves,” his scathing assessment of America’s third president, was published last month. But just how rough he may not have realized.

True, Mr. Wiencek, an independent scholar, has received the kind of attention most authors can only dream of: book excerpts on the covers of both Smithsonian and American History magazines, a C-Span interview at Monticello, almost universally glowing reviews from nonspecialists. (Jonathan Yardley of The Washington Post called the book “brilliant,” while Laura Miller of Salon hailed it as one “every American should read.”)

But the Jefferson scholars who have weighed in have subjected “Master of the Mountain” (published by Farrar, Straus & Giroux) to a fierce barrage of criticism, blasting away at Mr. Wiencek’s evidence, interpretations and claims to originality. Reviewing the book in Slate, Annette Gordon-Reed, a professor of history and law at Harvard and the author of the Pulitzer Prize-winning study “The Hemingses of Monticello,” declared that it “fails as a work of scholarship,” recklessly misreading documents and dismissing other scholars in pursuit of a “journalistic obsession with ‘the scoop.’ ” Jan Ellen Lewis, a historian at Rutgers University, writing in The Daily Beast, was even blunter, denouncing the book as a “train wreck,” written by a man “so blinded by his loathing of Thomas Jefferson that he can’t see” contrary evidence “right in front of his eyes.”

The divergence of response would seem to highlight the difference between the ways professionals and lay readers approach history, not to mention the sometimes tense relations between academic historians and independent scholars working the same beat, especially one as charged and contentious as the relationship between the founding fathers and slavery.

Mr. Wiencek (pronounced WIN-seck), the author of a well-regarded earlier book about George Washington and slavery, certainly sees it that way.

“Inside the Jefferson bubble, they are trying to discredit this,” he said recently in a telephone conversation from his home in Charlottesville, Va., a few miles down the road from Monticello. “It presents an image they don’t like.”

Mr. Wiencek’s main contention is that sometime in the 1790s, Jefferson became so convinced of the economic value of slavery that he completely abandoned his youthful antislavery sentiments.

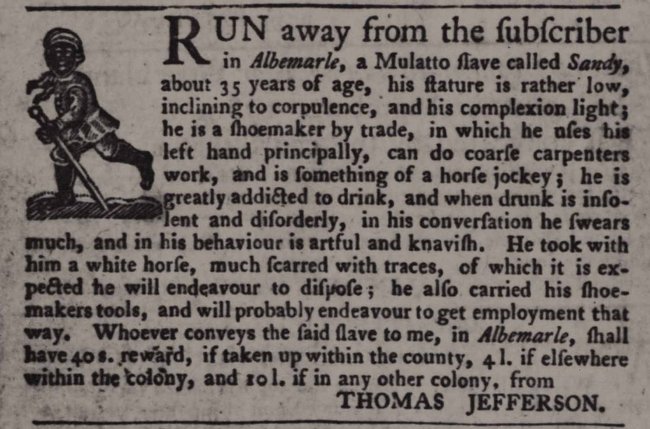

To bolster his argument, Mr. Wiencek points to a note in the margins of a 1792 report to George Washington that he believes shows Jefferson, then serving as secretary of state, calculating the birth of slave children as delivering a reliable return on capital of “4 percent per annum” — a note, he claims, that no writer on Jefferson has ever mentioned.

In their reviews, Ms. Lewis and Ms. Gordon-Reed dismiss this “4 percent theorem,” as Mr. Wiencek calls it, as a speculative back-of-the-envelope calculation about slavery in Virginia as a whole, not evidence of any turning point in Jefferson’s thinking about his own investments in human property at Monticello.

But Mr. Wiencek defends his interpretation of the document, doubling down on what he sees as a “core truth” behind Jefferson’s lifelong equivocations about the evils of slavery.

“It was all about the money,” he said. “By the 1790s, he saw them as capital assets and was literally counting the babies.”

When it comes to his critics, Mr. Wiencek is equally direct: “They have turned what could have been a reasoned debate into a mudslinging fest.”

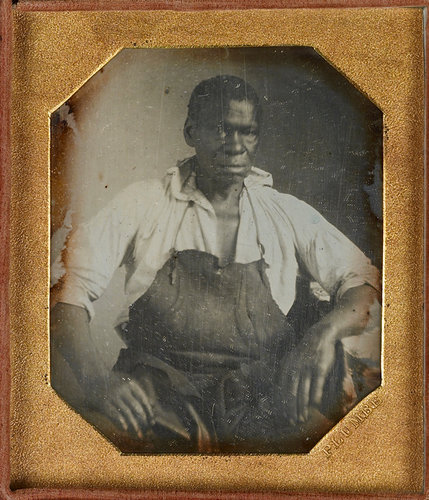

Special Collections Library, University of Virginia / Isaac Granger, a slave at Jefferson’s Monticello.

But even some who are sympathetic to Mr. Wiencek’s dark view of Jefferson say that if there is mud flying, Mr. Wiencek set it off by writing a sensationalistic book that repackages the work of scholars who have spent decades fighting for a full acknowledgment of Jefferson’s entanglement with slavery, only to be painted now as apologists for the man.

“I think Thomas Jefferson is one of the most deeply creepy people in American history,” said Paul Finkelman, a professor at Albany Law School and the author of “Slavery and the Founders,” which outlines the evasions of earlier generations of Jefferson scholars. “But for Henry to come along and say, ‘I am the first one to discover this’? Come on.”

Mr. Wiencek acknowledges some truth in the charge that he is repackaging the work of others, but defends his book as a real contribution.

“Yes, I’m repeating some of information that others have brought out,” he said. “But others brought it out and buried it in footnotes. I brought it all together. I connected the dots.”

Historians, however, tend to read footnotes first, and some have raised eyebrows at what they see in Mr. Wiencek’s. In particular, they point to his treatment of the work of Ms. Gordon-Reed, whose 1997 book, “Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings: An American Controversy,” was instrumental in breaking down the wall of resistance to the idea that Jefferson had a sexual relationship with Hemings.

Ms. Gordon-Reed’s name appears nowhere in the body of the text but three times in Mr. Wiencek’s endnotes, twice to mention her “erroneous and misleading” transcriptions of key documents relating to Hemings.

David Waldstreicher, a historian at Temple University and the author of several books about slavery and the founders, called those footnotes (which do not identify the errors or acknowledge that Ms. Gordon-Reed corrected one of the transcriptions a decade ago in a reissue of her 1997 book) “fighting words” and “about as nasty as it gets.” A professional historian, he continued, “would publish this in a scholarly journal and make it very clear how it makes a difference, instead of using it to say, ‘I am the last word.’ ”

Mr. Wiencek said in the interview that the transcription errors were minor. But his third reference to Ms. Gordon-Reed cuts to the heart of a larger continuing debate in the writing of academic history: How does one balance, or, now, rebalance, the shift from focusing on men of power, like Jefferson, to exploring the ways women, slaves and other marginalized people shaped their own destiny?

At the close of his book, Mr. Wiencek quotes a sentence from “The Hemingses of Monticello” as an example of the way two decades of scholarship that emphasizes the “agency” of slaves implies, as he puts it, that they “had no master.”

Ms. Lewis, in an interview, called that passage a “profound misreading” of Ms. Gordon-Reed’s work. “There are historians who in their eagerness to discover the slave perspective have averted our attention from the ways in which slavery really was a horrible, unjust institution, but he doesn’t cite them,” she said. “Instead, he cites Annette Gordon-Reed? You’ve got to be kidding me.”

Since his book was published, Mr. Wiencek has been more direct in his claims, asserting that his work “systematically demolishes” Ms. Gordon-Reed’s portrayal of Jefferson as “a kindly master to black slaves.”

But Ms. Gordon-Reed, for her part, scoffs at the idea, noting that her books discuss many of the same instances of cruelty at Monticello that Mr. Wiencek cites. “That was Jefferson’s image of himself, as a benevolent slaveholder,” she said. “My work shows that’s impossible.”

Even some of the scholars who helped Mr. Wiencek have turned against him. In his acknowledgments Mr. Wiencek, who received a research fellowship from the International Center for Jefferson Studies, thanks Lucia Stanton, the recently retired chief historian at Monticello, whose decades of research on slavery at the plantation he credits with breaking “the seals on many hidden histories.”

But in a letter last month to The Hook, a Charlottesville newspaper that ran an articleabout “Master of the Mountain,” Ms. Stanton blasted him for a “breathtaking disrespect for the historical record and for the historians who preceded him,” including Edwin M. Betts, whose 1953 edition of Jefferson’s plantation records Mr. Wiencek claims deliberately left out a passage indicating that Jefferson knew that very young enslaved boys in the Monticello nail factory were being whipped.

“How can he know that Betts ‘deliberately’ suppressed this sentence, in what was a compilation of excerpts, not full letters?” she asked, noting that Betts’s edition contains many far worse details about Jefferson’s treatment of slaves.

Mr. Waldstreicher said Mr. Wiencek had raised legitimate questions about the editing of Jefferson’s farm records that scholars would need to untangle. But for the moment, Mr. Wiencek is not going to get the public forum with Ms. Gordon-Reed he says he is eager for. The museum at Poplar Forest, Jefferson’s other plantation, in Lynchburg, Va., has invited both of them to appear on a panel. Ms. Gordon-Reed, however, has declined.