17 July 2013

Colin Grant writes memoir

about growing up

Jamaican in Luton

By Carla Parks / Ariel Reporter

It’s not an easy thing to write candidly about your past, because memory is often a slippery and wriggly thing. Not to mention that revisiting past events can be painful. For Colin Grant, writing about his childhood in 1970s Luton gave him a different perspective on his larger-than-life, irascible father with a ‘titanic temper’.

“For many years I feared that my father would die before I had a chance to kill him” — Colin GrantWriter

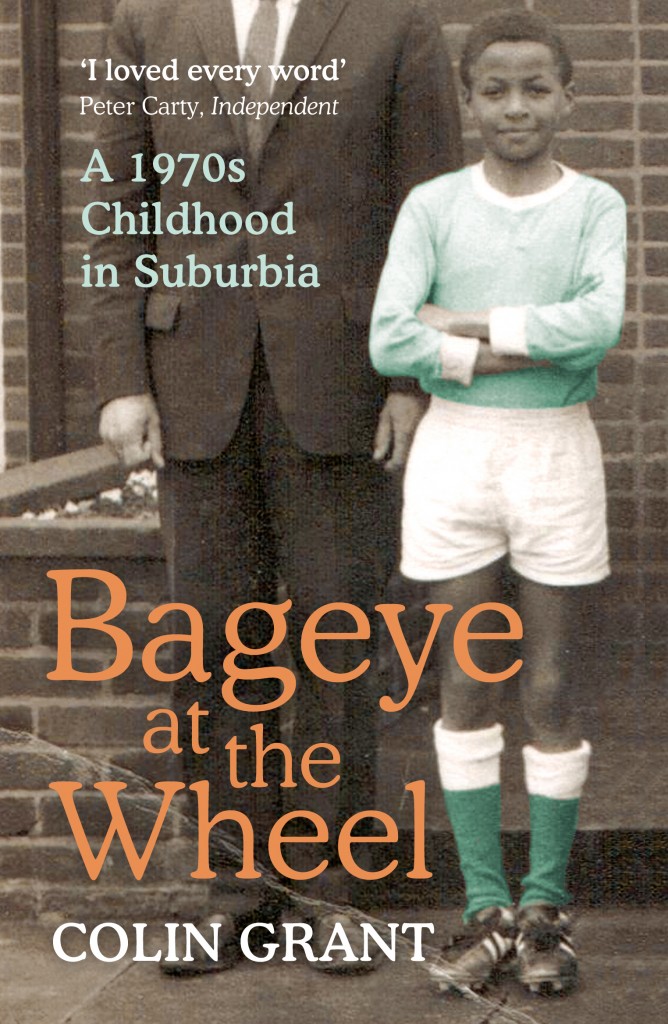

Bageye at the Wheel is Grant’s personal tale of immigration, about a large Jamaican family struggling in England. It’s also a book that deals with the complex relationship between a father and son.

Grant, a producer in the science unit, speaks eloquently about writing the book – nominated for the prestigious Pen/Ackerley prize for memoir – and admits it wasn’t easy.

‘There were some fixed ideas I had about the past that when I reinvestigated them were not so solid. And sometimes you cling to the past like a wreckage, like a seaman clinging to the ship, fearing to strike out from the sinking ship in case he sinks.’

At the heart of the story is his father Bageye, a nickname given to him because of the puffy bags under his eyes. The author explains how his mother and siblings would also call his father Satan, and that Grant spent much of his childhood plotting devious ways of killing him.

In some of his boyhood fantasies he would put shards of glass into his father’s food or lift the carpet on the stairs so that he’d trip and break his neck. ‘For many years I feared that my father would die before I had a chance to kill him,’ Grant says in a deadpan voice. ‘I had to reconcile myself to writing a book that would satisfy the reader but wouldn’t be an act of revenge.’

Glamour and gambling

Sitting inside the opulent splendour of RIBA near Broadcasting House, Grant tells me that Bageye was not a model father, but a human one with many foibles. He worked on the production line of Vauxhall Motors and spent every Friday evening at Mrs Knight’s weekend gambling house in their mainly Irish neighbourhood.

Here, his father and his friends would ‘fry their chicken and prepare their rum and Coke and have a merry old time’. Grant’s job was somewhat less glamorous. On Saturday afternoon, ‘I would stand at the poker table and embarrass my father into giving us his house money because, otherwise, come Sunday morning, he and his friends would emerge from Mrs Knight’s blinking into the sunlight penniless.’

Grant’s parents, who had an unhappy marriage, divorced when he was a child – and this left him feeling guilty. ‘I always thought that I had somehow failed as a child, failed my father, because my parents decided that they would split when I was a young boy.’ He describes himself as a ‘conduit’ between his parents and also between a world that was Afro-Caribbean and Anglo Saxon.

“The book is a kind of love letter to him. It’s not an unbridled love letter, it’s a tough-but-tender love letter to him and the past”—Colin Grant, Writer

He touches on these themes in his book, which is inflected with the rich patois of Jamaica. But though it could have been a bitter recounting, the writer insists that Bageye at the Wheel is filled with humour and tenderness for its subject. ‘In the course of writing the book I think I became more sensitive to [Bageye]. The book is a kind of love letter to him. It’s not an unbridled love letter, it’s a tough-but-tender love letter to him and the past.’

Diverse voices

It’s also a reflection on the 1970s, an era of sofas covered with plastic and of ambitious DIY projects that failed.

Grant summons up the humorous, colourful side of his Jamaican heritage, surrounded by people with names like Summerwear, because he insisted on wearing summer suits year-round, or Tidy Boots, who was fussy about his footwear.

The writer has drawn some of his inspiration from Caribbean Voices on the World Service, where he started his career at the BBC, ‘cutting my teeth’ by writing scripts. He discovered the giants of Caribbean literature – V S Naipul, George Lamming and Samuel Levon.

He says that he wanted to capture ‘their flavour and vitality’ in his writing – but he was left frustrated that more Caribbean authors hadn’t chosen to write about their immigrant experiences in more depth. ‘There have been a few scatterings of Afro-Caribbean writing in this country, but not many and I wanted to close that gap,’ he says.

‘Black hole’

He calls the gap ‘a black hole’ that needed illuminating. Bageye at the Wheel is his third work that deals with Afro-Caribbean themes. The first was a non-fiction book about Jamaican nationalist hero Marcus Garvey called Negro With A Hat. It has been optioned for film, with broadcaster and playwright Kwame Kwei-Armah writing the screenplay.

His second was about The Wailers, the band made famous by Bob Marley. It has also been optioned for a feature film about Peter Tosh.

But though Grant’s writing has met with some success, he doesn’t write to make money or for fame – but because it’s something that excites him. Grant gives full credit to his manager Deborah Cohen for enabling his passion. ‘It’s a testament to her that I’ve been able to write Bageye at the Wheel.’ He says she’s created an environment where everyone thrives, both at work and beyond that.

The producer, who lives in Brighton, undoubtedly benefited from having an understanding manager at times – there have been many sleepless nights and an obsession with Marcus Garvey that ‘almost killed me’.

‘It’s no secret to say that my wife thought I was a bit disturbed when I was writing that book,’ he laughs. ‘I had no sleep, really, and I would be at the computer with my back to her when she went to bed and she would wake up and I’d still be in that position.’

Reunion

A father of three, Grant says his children have read all of his books, even if they haven’t always shared his enthusiasm for his work. ‘I’ve illuminated that black hole that I grew up with so that they don’t have to live with it,’ he judges.

As for his father, now 84, the memoir has acted as a means for a reunion, because Grant had to seek Bageye’s permission to publish the book. ‘I hadn’t seen him for 32 years, so the first time I see him is to take him this memoir, which has his face on the cover.’

The writer was nervous and he hid the proof under his two already-published books. His father took these and then they went to a West Indian pub, where they talked and caught up. ‘Towards the end of our time there, my father stood up and addressed the crowd in the pub and he held up the proof and said, “My son has written a book about me.” He was enormously proud and flattered by it.’

And so he should be.

>via: http://www.bbc.co.uk/ariel/23253460